World War I Germany Had an Official Hate Song. Brits Made It a Joke.

The pen is mightier than the sword — or at least that’s what German officials during World War I were thinking when they propagated the “Haßgesang ,” or "Hate Song," known in the English-speaking world as the “Hymn of Hate.”

Yet the Germans' attempt to harness the power of music to punish their enemies backfired spectacularly — thanks to Britons' legendary sense of humor.

Composer Lissauer didn't like England

This ode to hatred was one of the war’s strangest phenomena. It was penned by Ernst Lissauer, a German-Jewish writer who considered himself a German nationalist and wrote pamphlets to incite animosity against England during the war. (One of his wartime poems, "England träumt _, " _or “England Is Dreaming,” fantasizes about Germans bombing England at night while unsuspecting people sleep.)

Lissauer also coined the well-known phrase “Gott strafe England!” — “May God punish England!” This became an official German slogan of World War I, appearing on postcards, placards, graffiti, dishware, pins and badges. (The word "strafe," today used in English to denote aerial attacks with bombs or machine guns, in fact derives from this phrase.)

In 1915, Kaiser Wilhelm II was so pleased by the song and the ensuing spread of hatred throughout his country that he decorated Lissauer with the Order of the Red Eagle, Fourth Class. Crown Prince Rupprecht, commanding the Bavarian Army, had pamphlets of the song distributed to his troops, evidently hoping it would fire them up on the battlefields of the Western Front.

GET HISTORY 'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit

An Ode To Anger

The “Hymn of Hate,” first published in 1914, became a worldwide sensation because of its length and vehemence. The rant employs representations typically used by German right-wing nationalists: imagery of uniformed officers, oaths, steel and Germans united in lockstep.

However, the poet evidently came up at a loss for words to demonize England. Like many German nationalists unfamiliar with Great Britain, he assumed the “English” must be “merchants” because of the British Empire’s worldwide trade network. Thus he threw in commerce-related gibes, such as "building walls from bars of gold" — conveniently ignoring the Kaiser's own attempts at empire- building.

He also took aim at England’s climate, citing seawater and gray weather to paint a picture of gloom despite the fact that Germany borders the North Sea and is not a particularly sunny country itself.

He [England] is known to you all, he is known to you all,

He sits crouching behind the gray waters of the sea,

Full of envy, of rage, of slyness and craftiness,

Separated by water that is thicker than blood.

Ernst Lissauer

From german Solemnity …

The “Hate Song” was taught in German schools, sung at concerts, distributed on pamphlets and was in all respects placed front and center in the public eye.

“We do not want our hate to abate. We all united have one hate. We love in unity, we hate in unity, we all have only one enemy — England!” raved the lyrics.

The first English translation of this ode to anger appeared in the United States in 1914, where it was described by The New York Times as “abominable,” “brutal,” and “wicked,” before crossing the Atlantic and being reprinted in The Times of London, where an editorial acknowledged, with typical British understatement, “There is something frightful about it.”

The "Hymn of Hate" against England was

extremely popular in World War I Germany. In addition to being taught in

schools and recited in public, it was also set to music, such as in this

composition by Franz Mayerhoff for a male chorus published in 1915. The cover

art of the pamphlet depicts a German in medieval armor, a image popular with

German nationalists that also later appeared in Nazi propaganda in the 1930s

and during World War II. (SLUB Dresden)

… to English Hilarity

It wasn’t long before Germany’s favorite new hate anthem became the subject of incorrigible British humor, causing the song itself to backfire against the Germans in propaganda. The verses had a comic effect on English audiences and, ironically, the “Hymn of Hate” became popular among the people intended to be the object of Germany’s hatred.

Lissauer’s diatribe might have evoked solemn wrath for German audiences, but the cool-headed British were convinced their opponents had gone hysterical. The “Hymn of Hate” quickly lost its bite as people in Great Britain and the Commonwealth nations giggled at the thought of scowling Germans being in a perpetually sour mood and venting litanies of anger.

In 1915, the Royal College of Music decided to perform the “Hymn of Hate” as a joke. It was apparently the brainstorm of English composer Hubert Parry and famed organist Walter Parratt, who directed the choir. They had no accompanying music to set it to and thus composed something themselves. The choir was instructed to be serious and sing “with plenty of snarl,” which proved difficult.

“They laughed too much to snarl. However, when they came to the word ‘England,’ they rolled it out in fine style,” Parry told The Times in 1915. “It was great fun. … I felt like sending Lissauer a telegram telling him how much we had enjoyed his work and what infinite amusement it had afforded us, but I did not see how I was going to ensure the telegram reaching him.”

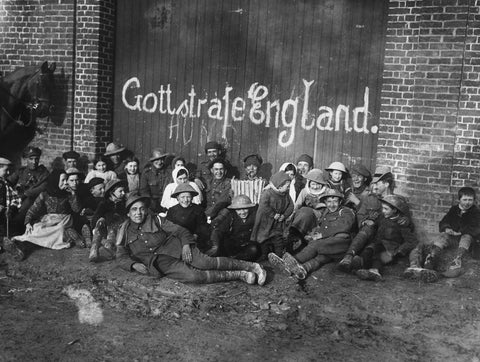

British and

American soldiers on the Western Front smile as they read a newspaper during

World War I. The "Hymn of Hate" became a favorite subject for parody in

English-speaking countries, with related satire appearing in newspapers. The

band of Britain's Coldstream Guards performed a joke version of the "Hate

Song" for American soldiers in the U.K., which proved popular and reportedly

inspired a ragtime version. (National Library of Scotland)

In July 1915, a parody allegedly written by an unnamed soldier on the Western Front appeared in New Zealand newspapers. Called “The Tommy’s Song of Hate,” the verses criticize a Prussian soldier sneaking under a wire obstacle to steal custard pudding from British soldiers.

“I hate as one and I hate as four,

I hate the hate of an army corps;

One hate I have and one hate I hiss,

An’ I call the perishin’ blighter this:

PUDDEN-PINCHER”

Anonymous

Popular British music hall singer Tom Clare entertained audiences with, “My Cheery Little Hymn of Hate,” an ominous piano tune in which he wishes to “strafe” men who smoke cheap tobacco, scantily clad revue girls, people who cough in churches and a variety of other unusual individuals and situations, lapsing into an absurdly joyful refrain.

The Coldstream Guards’ band developed their own comic version which they played for American soldiers in reserve camps in Great Britain. The Deseret News in 1918 reported that the song made a “Hit At American Camps — Rag Time Version Next in Order.”

Hating the Hate song

Meanwhile, the Germans were not oblivious to the parodies, nor to the criticism of promoting a song that was viewed by many as melodramatic and emotionally unhinged. Nor were German nationalists — who were composing their own hateful propaganda — content to share fame with Lissauer, thanks to his Jewish background.

Antisemitic German writers began heaping criticism upon Lissauer, showering him with discriminatory tropes and insisting the song was in fact “un- Germanic” — despite its popularity and the fact that the kaiser had endorsed it. At the same time, members of the Jewish community in Germany and abroad sought to distance themselves from Lissauer and his verses.

Thanks to Lissauer's efforts, hatred had become a public virtue in German. And now his enemies unleashed the hatred against Lissauer. He justified his verses and defended himself from an increasing number of critics and enemies, but his attempts proved useless.

Eventually exiled from Germany, Lissauer moved to Austria. Prior to his death in 1937 he left instructions that nobody should publish the “Hymn of Hate” in any collection of his works. Adolf Hitler annexed Austria a year later.

Despite Lissauer's wishes, his legacy remains predominantly associated with the aggressive nationalist propaganda he created during World War I.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.