Toss Grenades from an Open Cockpit? In 1911, an American Soldier Had a Better Idea

On November 1, 1911, Italian Sub-Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti leaned over the edge of the cockpit of his Etrich Taube monoplane.Below him he could see a camp in the Libyan desert that was occupied by Turkish-supported Bedouin troops who were battling the Italians in the Italo-Turkish War. Gavotti identified his target and then, one by one, dropped four grapefruit-sized grenades, each weighing four pounds, over the side of his airplane into the enemy camp. The grenades inflicted no casualties, but they did enter the history books.They were the first bombs dropped from an airplane in war.

They were not, however, the first bombs dropped from an airplane.

It did not take long after the Wright brothers made their historic airplane flights in December 1903 before people began considering how to turn the flying machine into a war weapon. As early as 1906 the U.S. Army’s Ordnance Chief, Brig. Gen. William Crozier, was thinking about the concept, although he thought it would be easier to drop bombs from a balloon than a rapidly moving airplane, and he stressed the importance of avoiding “the destruction of Red Cross hospitals, churches, seminaries, and all the establishments usually immune in time of bombardment.”

In fact, people had already dropped bombs from balloons. The first tactical military use of airborne bombs took place in July 1849 during an Austrian siege of Venice. The Austrians launched unmanned paper balloons—exactly how many is not known, and reports range from two to 200— from the paddle-wheeler Vulcano, the world’s first aircraft carrier. Each carried a bomb with up to 30 pounds of explosives. The details of the attack remain obscure, but the idea apparently came from Lieutenant Franz von Uchatius of the Austrian artillery. The results were not what the Austrians had hoped. Said one account, “[T]he balloons appeared to rise about 4,500 feet. Then they exploded in midair or fell into the water, or, blown by a sudden southeast wind, sped over the city and dropped on the besiegers.” Venetians who had gathered outside to watch the spectacle cheered and clapped when the bombs exploded over the Austrian lines.

In North America a few years earlier, visionaries suggested using balloons to drop bombs on Vera Cruz during the Mexican-American War or employing them to subdue Apaches in the Arizona desert, but nothing came of those ideas. In the United States in the 1890s and early 1900s, dropping explosives from balloons at state fairs became a fad. By the end of 1908, balloonist Roy Knabenshue had used a dirigible to demonstrate how easy it would be to attack an unsuspecting city from the air. He flew over Los Angeles at 10:00 p.m. to show that a powered airship couldn’t be heard or spotted during the night and dropped two bags full of confetti onto the unsuspecting people below. In March 1909 the Westminster [Md.] Democratic Advocatewas encouraging the creation of an aeronautical defensive force. The article wondered what would happen if an enemy air fleet dropped explosive devices on New York City’s skyscrapers, “wrecking them completely.” The paper speculated about future air combats, asserting they “would be battles royal.” Six months later Ronald Legge published a novel called The Hawk: A Story of Aerial War. Set in London, the book told the story of the Hawk, a gigantic military dirigible that the British used to drop “terror and destruction” on invading Germans and Frenchmen. Around the same time, an aeronaut whose name is lost to history circled above New York and dropped harmless projectiles onto the roofs of buildings. In May 1909, Boston millionaire Charles Glidden announced plans to drop eggs in place of “bombs and hand grenades” on his home town “to determine the accuracy of this kind of warfare,” according to an article in the United Press.

this article first appeared in aviation history magazine

Obviously, the idea of taking warfare into the skies was gaining currency. Even Theodore Roosevelt was thinking about it. When pioneering aviator Arch Hoxsey took the former president aloft over St. Louis in October 1910, Hoxsey reported that Roosevelt became excited when he spotted a fake canvas-and-wood battleship that had been constructed for the airshow. In the ensuing torrent of words from the ex-president, Hoxsey was able to make out “war,” “army,” “aeroplane” and “bomb,” and he realized Roosevelt was seeing the faux vessel “with the keen eye of a man who saw the real battleship that could have been put out of business with a bomb.”

A month later, at an air meet in Baltimore where Brig. Gen. James Allen, chief of the Army Signal Corps, became the first senior army officer to fly, the program included a “bomb-throwing” event. Competitors vied for a $5,000 prize offered by the Baltimore Sun by dropping bags of flour on a life-size outline of a battleship deck. Frenchman Hubert Latham won the event by collecting 15 points on six drops—one of which would have “dropped into the funnel of the battleship.”

Aviators bombed another battleship outline, this time using oranges, at the Los Angeles International Air Meet that December. Arch Hoxsey participated, and the Los Angeles Herald reported that when he ate one of his oranges the judges made him forfeit three points. (Hoxsey died in an airplane crash the next day.)

But the Army had already been thinking along Roosevelt’s lines. The year before Roosevelt took to the air, Army Lieutenant Paul W. Beck participated in Los Angeles’ first air meet as a passenger. The San Francisco Examiner reported that from 250 feet he dropped “small canvas money bags packed with sand, each weighing around two pounds.” He was not happy with the results, writing that “the accuracy should have been spelled with an ‘in’ in front of it.” Beck next served as the secretary for an air meet held the next month in San Mateo County, 12 miles south of San Francisco. The venue was a makeshift airfield constructed alongside a horse racetrack and named Camp Selfridge in honor of Army Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, a native San Franciscan who became the first airplane fatality in 1908. Beck took advantage of the event to direct some military experiments, marking the first time the United States Army and Navy officially took an active role in experimenting with aircraft.

It was at the San Francisco meet in January 1911, that Army Lieutenant Myron S. Crissy of the 70th Coast Artillery designed and tested the first bomb specifically intended to be dropped from an airplane. Born in Bay City, Michigan, in 1881, Crissy had graduated from West Point in 1902. The bomb he built was pear shaped and had two sticks, 2.5 feet long, a half-inch thick and three-quarters of an inch wide, attached to its front end to keep its nose down as it fell. With financing from local businesses, Crissy had the six-pound bomb constructed at a local iron works and packed it with bullets and a half-pound of common black powder.

Before putting his bomb to the test, Crissy had to figure out how to drop it from an airplane. He consulted old Army ordnance tables from the time of the War of 1812—believing that the older powder charges would be more applicable than modern ones when it came to the low speed of a bomb dropped from an airplane—and studied the way air currents affected differently shaped projectiles.

On January 15, Crissy went aloft with a civilian pilot named Phil Parmalee (who had competed with Hoxsey in the orange-dropping competition) and released a bomb from a height of 550 feet. Parmalee said the airplane was traveling at about 45 mph when Crissy released the bomb and he banked the airplane to watch its descent. He and Crissy could not hear the explosion, but they could see its effects. Aided by the drop angles he had calculated, Crissy placed his bomb within two feet of a large X marked on the ground and blasted a hole two feet deep that was “about the size of an ordinary wash tub,” according to Crissy. He added that “the bullets with which the shrapnel had been loaded were so widely scattered that barely a third of them could be found and recovered.” An article in the Salt Lake Tribunestated that the bomb’s “destructive zone” had a 70-foot radius.

“This was my first experience in an aeroplane but it isn’t going to be my last,” Crissy told a local paper. “I am convinced that accurate throwing of bombs from a machine at great heights is entirely feasible,” he said, and speculated about rigging a tube or chute so aviators could drop bombs with more accuracy and prevent a dropped bomb from hitting the airplane on release. He also said that he had already designed a more powerful bomb.

Crissy and Parmalee were at it again two days later, this time dropping a pair of bombs. The first one, released from 680 feet, “splashed in a mud puddle near the target” but failed to explode, the San Francisco Callreported. The second landed eight yards from the target—leaving a hole “two and a half feet square and nearly three feet deep [with a 50 yard] zone of destruction.” Crissy was pleased with the result, writing that it “proves the accuracy of bombarding from the skies…taking into account the velocity of the wind and the speed of the aeroplane, both of which I figured out before I released each shell.”

Lieutenant Beck described Crissy’s next bomb design as cylindrical in shape, with “a truncated conical nose” and weighing 20 pounds. This time Crissy attached an 18-inch-long rod with a pair of propellers to the bomb’s nose. As the bomb fell, the wind-driven propellers would make it rotate like a spiraling football, keeping it on a straight course and helping it penetrate deeper into the ground. To drop these heavier, more complex bombs, Crissy planned to attach them to the airplane and release them by either cutting or jerking a cord.

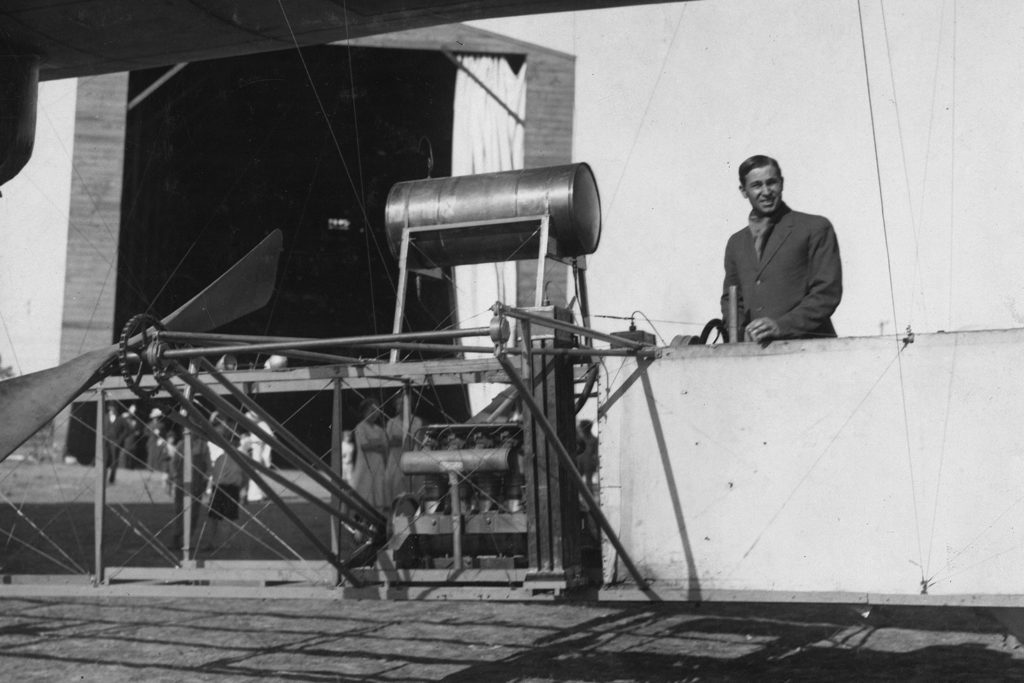

The drop was scheduled for January 22, 1911, this time with Charles Willard (another orange-dropping competitor) piloting a Wright biplane. Crissy found that the airplane’s bracing wires made it difficult to drop the bombs and he did not place explosives in his projectiles, fearing that they would fall too close to the meet’s grandstand. He said he made the drop mainly to calibrate fuses. According to Beck the two bombs were released “from altitudes varying between five and seven hundred feet, each producing a close shot.” Crissy planned to drop a live bomb the following day, but foul weather intervened.

That ended Crissy’s experiments with dropping bombs from airplanes, but others were more than happy to pick up where he left off. Before the year was out, Lieutenant Gavotti entered the history books when he dropped his four grenades on the enemy. Unlike Crissy’s projectiles, though, Gavotti’s bombs had not been designed to be dropped from the air. In October 1912, Captain Simeon Petrov, an engineer and member of the Bulgarian army air force, developed several bomb prototypes by taking grenades, adding fins and increasing the amount of explosive. On November 17, 1912, Major Vasil Zlatarov, riding as a passenger/bombardier with pilot Giovanni Sabelli (an Italian volunteer), dropped one of those bombs during the First Balkan War, fought by the Balkan League (Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece and Montenegro) against the Ottoman Empire. Petrov’s design—fins attached to a square explosive device—was hardly aerodynamic, but it provided the next step in the evolution of the aerial bomb.

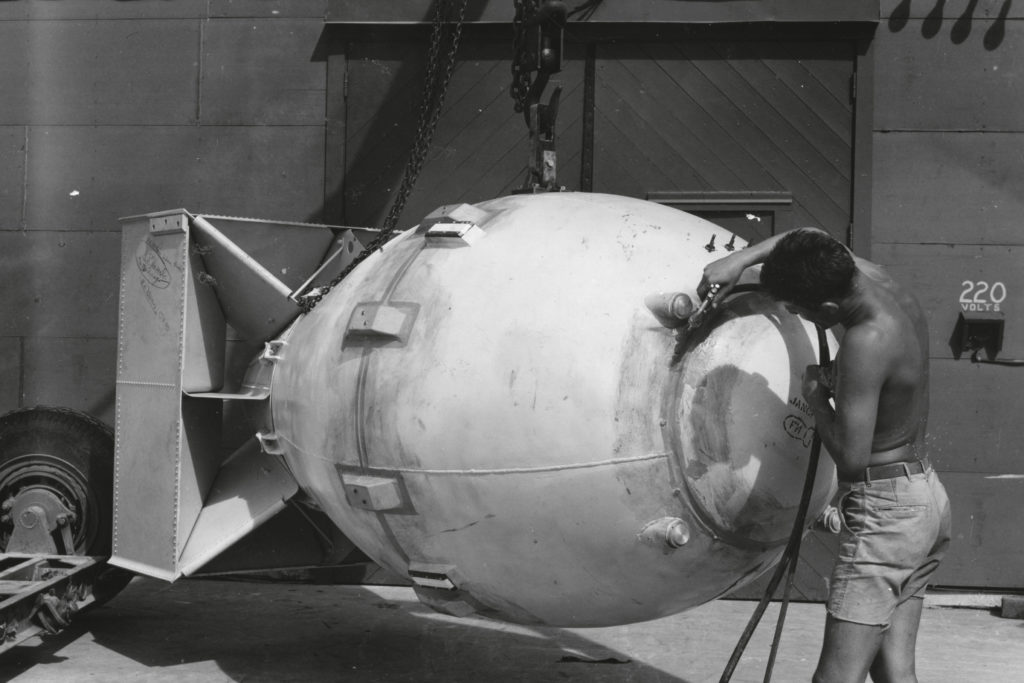

Myron Crissy lived long enough to see his idea taken to its most horrifying extreme, with the atomic bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki less than 35 years after he had conducted his first experiments. Just as the Boeing B-29 Superfortresses that dropped them were a far cry from the wood-and-fabric airplanes that Crissy used, the atomic bombs dropped on Japan were many orders of magnitude removed from his primitive experiments. The Hiroshima bomb, Little Boy, weighed almost five tons and had a yield equal to 15,000 tons of TNT, while Fat Man—the Nagasaki bomb—was even larger, weighing in at nearly 11,000 pounds and exploding with the force of 21,000 tons of TNT. In Crissy’s day a height of 550 feet was considered a perilous attitude; the B-29 Enola Gaydropped the Hiroshima bomb from 31,000 feet. Gavotti’s historic bombing raid hurt nobody; the atomic bombs and their radiation each killed about 140,000 people.

Perhaps Crissy pondered about his role in the path that led to such destructive power being rained from the skies—not just over Japan but also during the strategic bombing campaign over Europe, during which Allied airplanes dropped some 2,700,000 tons of bombs. After his history-making bomb experiments in 1911, Crissy remained in artillery. During World War I he was slated to command a field artillery regiment, but the war ended before he could carry out the assignment. After World War I he became involved in grave registration and the return of more than 4,000 U.S. dead to the United States. Throughout the 1920s, Crissy served in various administrative capacities involving the reserve army. He was forcibly retired for a disability in 1934 as a lieutenant colonel. Crissy died in 1946 at 66, the unacknowledged father of bombardment by airplane.

Daniel J. Demers is a retired businessman who writes about events and personalities of the 19th and 20th centuries. He holds a B.A. in History from George Washington University and an MBA from Chapman University. He and his wife Christina live in Portugal. For further reading, he recommends Governing from the Skies: A Global History of Aerial Bombing by Thomas Hippler.

This article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue–subscribe!