The Warriors Who Nearly Destroyed Cortés—Before Joining Him

On entering the state of Tlaxcala in what today is central Mexico, Spanish conquistadors under Hernán Cortés soon found themselves surrounded by tens of thousands of hostile warriors and fighting desperately for survival. Of all the peoples they had encountered since their arrival in Mexico nearly five months ago, none had offered such fierce and determined resistance. The Tlaxcalans showed little fear of either Spanish horses or riders, even grasping the lances of the cavaliers and seeking to overthrow their mounts.

One horseman, unable to wrench his lance from the tenacious grasp of an enemy and robbed of his forward momentum, was immediately beset by a throng of warriors who struck at his charger with terrible obsidian-edged broadswords, nearly beheading the animal. Struggling out from beneath his lifeless horse, the rider shielded himself from his assailants’ blows with upraised arm and rodela (a small steel shield, or buckler). He surely would have died on the spot had his fellows not rushed to the rescue. A sharp battle raged, as fierce as any waged over a Homeric hero, before the Spaniards withdrew with the rider and his saddle. The Tlaxcalans, after hacking further at the remains of the horse, carried off severed chunks for display to fellow countrymen, to prove the vulnerability of the beasts. The rider later succumbed to his wounds.

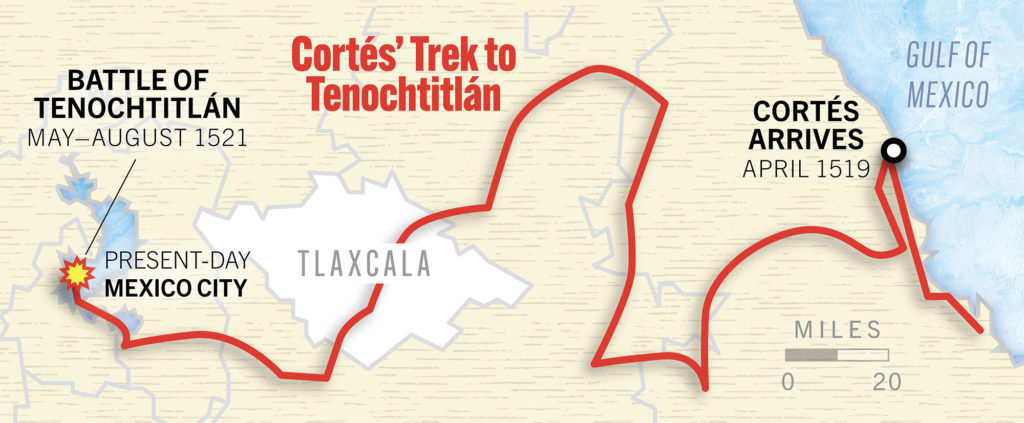

When Hernán Cortés landed on Mexico’s Gulf Coast in April 1519, he had only vague notions of what lay ahead. He knew the local people were subjects of a great empire governed by a mighty prince named Montezuma, who lived in a magnificent city in the interior. He also knew the Aztecs possessed wealth almost beyond the dreams of avarice, and he immediately began contemplating ways to make the most of the opportunities fortune had laid before him.

The force with which Cortés searched out his fame initially comprised 11 ships, 100 mariners, 508 soldiers—including 32 crossbowmen and 13 harquebusiers—16 horses, 10 heavy brass guns and four falconets—slender resources indeed with which to penetrate an empire whose territory held a population of many millions and whose influence stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Whatever other faults have been attributed to Cortés, an inability to make simple numerical calculations is not among them. It was crucial for him to win allies, and he ultimately had tremendous success in doing so. Tens of thousands of natives would aid the Spaniards as warriors, porters and laborers and by supplying food throughout the conquest of Mexico. Allies not only assisted Cortés in material terms but also boosted his authority in his dealings with Montezuma. Of his allies, the most remarkable—both because of their character and the efforts necessary to secure their friendship—were the Tlaxcalans.

Cortés greatly desired to secure an alliance with the Tlaxcalans, reported to be an independent, hardy and warlike people, undying in their hatred for Montezuma and unyielding in resistance to his rule. Yet long years of encirclement by their foes and frequent raids and invasions of their lands by vassals of the empire had honed the mistrust of the Tlaxcalans to a fine edge. They had gotten advance word of these strange visitors who had come in great ships, of the fantastic beasts on which they rode, and of their thunder and smoke that killed. They also knew the men from the sea traveled to see Montezuma and marched in the company of his vassals. Thus they naturally assumed the foreigners were servants of their mortal foe, come to destroy them.

As Cortés neared the Tlaxcalan frontier, he sent ahead two Cempoalan chiefs as envoys. After waiting two days with no word, the column resumed its march and soon encountered the terrified envoys. Having arrived in the midst of war preparations, they had been seized as suspected spies. The Tlaxcalans, they said, positively burned with the fervor of determined resistance. None would listen to the Spanish overtures of goodwill. The only reply to Cortés’ offer of friendship was a resolve, often repeated in the captives’ presence, that whether the intruders were supernatural beings or mortal men, the Tlaxcalans would tear out their hearts and gnaw the flesh from their bones. Threatened with the same, the envoys had managed to slip away from their inattentive guards. Undaunted, Cortés unfurled his banner and marched forward.

A force of some 3,000 screaming Tlaxcalans sprang from ambush, unleashing a hail of arrows and fire-hardened darts

The Spanish column had not traveled far when scouts reported some 30 Tlaxcalans ahead, equipped for battle and observing the column. Cortés ordered a detachment to capture one or more of them. But when the Spaniards beckoned with their hands and made signs of peace, the warriors mounted a furious attack. As the vanguard met their charge, killing five of the enemy, a force of some 3,000 screaming Tlaxcalans sprang from ambush, unleashing a hail of arrows and fire-hardened darts.

Cortés immediately ordered the rest of the column forward. Soldiers brought their harquebuses and crossbows to bear, and once rolled into position, the artillery barked out death on the massed attackers. The Tlaxcalans were well accustomed to the sounds of battle as they knew it—drums, horns, the thud of weapons striking flesh, the cries of men—but they entered a new realm of sensation as the report of firearms thundered in their ears, and terrible echoes rolled back from the surrounding hills. Death descended on thunderous wings. Yet while the warriors gradually gave way under this novel destruction, they did not flee. They retreated in an orderly fashion, maintaining their ranks. Encamping by a stream, the Spaniards spent an uneasy night sleeping in their armor with weapons ready. The horses remained saddled and bridled, and sentries and patrols kept vigilant watch.

The next morning they resumed the march, only to find their path blocked by an army of 6,000 warriors who made their deadly intentions clear through hostile demonstrations. Cortés once again tried diplomacy, sending forth three captives of the previous day’s fight bearing a message of peace. The message was ill-received. No sooner had the captives blended into the ranks of their fellows than the entire multitude began to howl with rage, their weapons and colorful plumage swaying like a forest whipped by storm winds. Battle was joined.

The Tlaxcalan fighters were no unruly mob, but an organized army with strict military discipline. Many were slain in the initial assault, and the survivors fell back. But their purpose was not swift victory; rather, by a gradual and controlled retreat they sought to lure their enemy forward into difficult terrain where many thousands of their fellows waited in ambush. When those warriors did spring the trap, the Spanish were in a fix, unable to adequately defend themselves on broken ground where their cavalry was of little use. Fighting their way through a shower of missiles past several ravines, they drew up on level ground and dressed their lines. Cortés realized that cohesion of their formation was the key to survival. As they were surrounded, any advance of the infantry would necessarily open gaps through which warriors might pour. The only mobile arm of the Spanish force was the cavalry, led by Cortés himself, which for the better part of an hour wheeled and charged endlessly within the shrinking sphere of open ground. Only after eight of their captains fell slain did the Tlaxcalans finally withdraw, concluding what the Spaniards would call the Battle of Tehuacingo, fought on Sept. 2, 1519.

The dawn of September 3 brought no fresh assault, so the Spaniards spent the day resting, repairing equipment and replenishing their stock of crossbow bolts. Cortés used the time for reflection. The courage and tenacity displayed by the Tlaxcalans in battle made them even more desirable as allies, yet they had met every attempt at amicable communication with threats or immediate attack. How, Cortés wondered, could he overcome the mistrust and hatred the Spaniards’ presence seemed to engender and establish diplomatic discourse?

Among the 15 captives taken on the second day of battle were two chiefs, and Cortés had them brought before him for questioning. To their surprise they had been well-treated and were thus willing to talk. From them Cortés learned much about the land and people of Tlaxcala. Each locality had its own lord, maintained and supported through a system of feudal dependency not unlike the structure that had long prevailed in Europe. Assembled in council, such lords represented the government of Tlaxcala, and each contributed forces for their mutual defense.

The chiefs informed Cortés their supreme commander was Xicotencatl, a most fierce and resolute man. It was he who adamantly maintained the Spaniards were spies of Montezuma and insisted on their annihilation. His was the banner spotted waving over the warriors who had fought with such ferocity, and his colors adorned their faces. Cortés emerged from council with the chiefs strengthened in his conviction the Spaniards must press on—continuing to extend diplomatic overtures, yes, but destroying all who rose against them. The next morning he led out a force to seek provisions in nearby towns and take prisoners, lest his foe infer from inaction the Spaniards had been weakened or discouraged by the resistance they had encountered.

Released from captivity, the pair of tlaxcalan chiefs later returned to Cortés with a message that peace would come only when the gods had been appeased with an offering of Spanish hearts and blood

Cortés returned to camp that afternoon with some 20 additional captives, who doubtless anticipated a horrible fate. Instead, they were fed, presented with beads and entreated by interpreters to lay down their anger and become brothers with the Spaniards. Cortés then set them free. He also released the two chiefs, directing them to bear another message of peace to the capital. Intercepted by sentries and taken before Xicotencatl, the pair returned to Cortés with a message that peace would come only when the gods had been appeased with an offering of Spanish hearts and blood. Adding to this bleak pronouncement, the chiefs reported that the combined forces of Tlaxcala had gathered to destroy them. Spanish padres kept busy all night hearing confessions.

The sun rose on men prepared for death. Thinking it better for morale to keep the men active than to wait in uncertainty, Cortés assembled the army. His remarks were practical rather than inspirational. All were to remain calm and methodical. Artillerymen were to direct their fire into dense groups of the enemy. Some crossbowmen and harquebusiers were to load while others fired, thus maintaining as continuous a stream of fire as possible without wasting ammunition. Swordsmen were to employ their points, thrusting into the bowels of their adversaries. Horsemen were to charge at half speed, restrain their mounts and aim their lances at the face and eyes of the enemy. None were to break ranks. To fail to maintain cohesive lines or succumb to exhaustion was to die. With those words of grim advice ringing in their ears, the men marched forth. Even the wounded, with the aid of their comrades, donned armor, grabbed weapons and kept pace as best they could, for all knew no man could be spared from this crucial contest.

They had not gone far when the Spaniards beheld the largest army they had yet seen in the New World. Sun glinting from spear points of copper and obsidian formed undulating waves of light above the throng of warriors. All shouted defiance and raised a fearsome war cry to accompany the thunder of drums. From what he had learned of native heraldry, Cortés could identify the banners of principal captains, as well as Xicotencatl’s personal armorial device—a white heron atop a rock. Beside it flew a banner emblazoned with a golden eagle on outstretched wings—the standard of the Tlaxcalan state. Spanish chroniclers estimated enemy numbers at anywhere from 50,000 to 150,000 men. Even at the low estimate, the position of the 400-odd Spaniards and their handful of Indian allies would have been akin to a sandcastle trying to hold back the sea.

No embassies were exchanged. When the Spaniards came into range, warriors released a spattering of missiles, which quickly became a torrent. Cortés and his men suffered their stings until reaching a distance more favorable for their guns and artillery. The volleys they fired into the densely packed enemy ranks inflicted dreadful carnage. The Tlaxcalans could not carry the dead and wounded from the field as quickly as they were struck down.

No longer able to endure this punishment, Xicotencatl’s warriors surged forward like a crashing tide. Spears and clubs hammered against the rodelas of the swordsmen as the latter strove to maintain the line. Their arms burned with fatigue as they repeatedly thrust into the bodies of a seemingly unending stream of attackers. Though crossbowmen and harquebusiers desperately poured fire into the enemy horde, the weight of numbers began to tell, and breaches opened in the Spanish line. Cortés bellowed orders but could not make himself heard above the din. For a moment it looked as though the Spaniards and their allies would be swept away.

Yet even as their victory seemed at hand, the Tlaxcalans were no longer able to sustain the attack. The price had been too high. The ground was littered with their dead and wounded, maimed and torn in ways they had neither experienced nor imagined. Their energy was spent, and the tide receded. The battle had lasted some four hours.

The Spaniards, nearly all wounded in one way or another, were utterly exhausted. As they staggered back to camp, the soldiers raised prayers of gratitude to God for their survival.

On the heels of his almost miraculous victory Cortés again sent envoys to the Tlaxcalan capital, seeking peace and safe passage. Angered rather than chastened by their army’s defeat, the lords rejected the overture and ordered Xicotencatl to mount a nighttime assault. Though he attacked with 10,000 of his best warriors, the Tlaxcalan commander fared no better, as the Spaniards were constantly on the alert.

On the heels of this latest failure the next day’s embassy received a more favorable reception. Among the elder lords, held in great respect, was the namesake father of Xicotencatl. He advised making peace with the Spaniards. Like Cortés, he thought the valiant soldiers from across the sea would make invaluable allies. Cempoalan envoys who had accompanied the Spaniards from the coast reported to the lords that Cortés had ordered Totonac settlements in the high sierra to cease paying tribute to Montezuma. The news allayed Tlaxcalan fears these visitors were servants of their great enemy and gave weight to Spanish declarations of goodwill. Heeding the elder Xicotencatl’s counsel, the lords ordered their army to cease attacking the Spaniards.

But the younger Xicotencatl, his blood up, was loath to lay down his arms and reaffirmed his intention to annihilate the Spaniards. Negotiations ground to a halt as the four chiefs chosen as ambassadors would not proceed for fear of the obstinate commander. The lords then got word to the army’s captains not to obey Xicotencatl unless he made peace with Cortés.

At last the commander agreed to send an embassy of 40 gift-bearing Tlaxcalans to the Spanish camp. His emissaries remained there overnight, making detailed observations. The alert Cempoalans suspected these men to be spies and warned Cortés that Xicotencatl had encamped nearby with the likely intention of mounting another nighttime assault. Convinced of the same after interrogating two of the emissaries, Cortés sent an uncompromising message. Taking 17 spies captive, he cut off the hands of some, the thumbs of others, and had these grisly trophies sent to their commander. The message the returning emissaries bore was unequivocal: Xicotencatl was to present himself in two days to accept the Spanish offer of peace, or Cortés would seek him out and destroy him.

The results of his gambit were immediate. The four ambassadors, no longer blocked by the army, approached camp that very day. Appearing before Cortés, they made deep obeisance and begged his pardon for having attacked him. The Tlaxcalans, they explained, had believed the Spaniards to be agents of Montezuma, who had never ceased in his attempts by force or fraud to invade their country. The ambassadors asked forgiveness for their error and accepted Cortés’ offer of friendship.

The Spaniards entered the capital of Tlaxcala on Sept. 23, 1519. Taking the lords aside, Cortés questioned them closely concerning interior Mexico and the Aztec empire. He heard again of the great power and wealth of Montezuma and was given a detailed description of the Aztecan capital of Tenochtitlán—the causeways by which it was approached, its fortifications, its infrastructure and its public buildings. The Tlaxcalan elders even brought pictures painted on henequen cloth depicting their battles with the Aztecs, from which Cortés learned much concerning Montezuma’s command structure and tactics.

The Spanish alliance with Tlaxcala continued to yield much of value throughout the conquest of Mexico. The Tlaxcalans provided supplies, fought alongside the conquistadors against the hostile vassals of Montezuma, gave the Spaniards safe haven after their initial expulsion from the Valley of Mexico, contributed warriors to the siege of Tenochtitlán and participated wholeheartedly in the final destruction of the hostile and oppressive Aztec empire. Cortés’ olive branch had fostered that successful military alliance. MH

Justin D. Lyons is an associate professor of history and government at Ohio’s Cedarville University. For further reading he recommends A True History of the Conquest of New Spain, by Bernal Díaz del Castillo; Conquest: Cortés, Montezuma and the Fall of Old Mexico, by Hugh Thomas; and History of the Conquest of Mexico, by William H. Prescott.