My Father, a WWII Veteran, Gave His Sergeant the Ultimate Honor

final homecoming

THE TRAIN PULLED INTO the station in Franklin, Tennessee, on December 16, 1948. It was 9:13 in the morning on a gray, overcast day. The temperature was in the 60s, warm for that time of year. On board were the remains of Technical Sergeant Lee Gordon Allen Jr.—“L. G.,” as he was known to his family and friends.

The article announcing his return was on page six of the afternoon edition of the Franklin Review-Appeal, tucked between Christmas ads for McClure’s department store and Tohrner’s Shop for Ladies. Were it not for the brief four-paragraph item in the local paper, his homecoming likely would have gone unnoticed by anyone outside of his family.

Sergeant Allen’s return home came exactly four years and two weeks after he was killed in a firefight with German soldiers in the French town of Sélestat. It was not unusual for so much time to pass between a soldier’s death and the return of his remains. After World War II, with 359,000 American dead scattered across both hemispheres, the military mounted a six-year recovery effort that yielded the remains of 281,000 fallen servicemen.

The low-key nature of his homecoming seemed a reflection of how L. G. appears to have lived his life: quietly, unassumingly, without fanfare. Still, if it is true that actions speak louder than words, Sergeant Allen’s actions on December 2, 1944, for which he was awarded the Silver Star, speak volumes about his bravery, his dedication to his troops, and his character.

My father, a private in Sergeant Allen’s unit, saw him not only as a leader but also as a mentor and, yes, as a good friend. And, it turned out, someone he was determined to remember in a special and very personal way.

forging a friendship

L. G. ALLEN WAS BORN on July 7, 1918, outside of Franklin, in a rural area of Williamson County. He was one of four children born to Lee Gordon and Minnie Allen. Allen enlisted in the army on December 6, 1939, at age 21. He had only an elementary school education. He served two years in Panama, re-enlisted, and was then stationed in Iceland for 18 months. In the spring of 1944, he was assigned to Camp Howze, outside Gainesville, Texas.

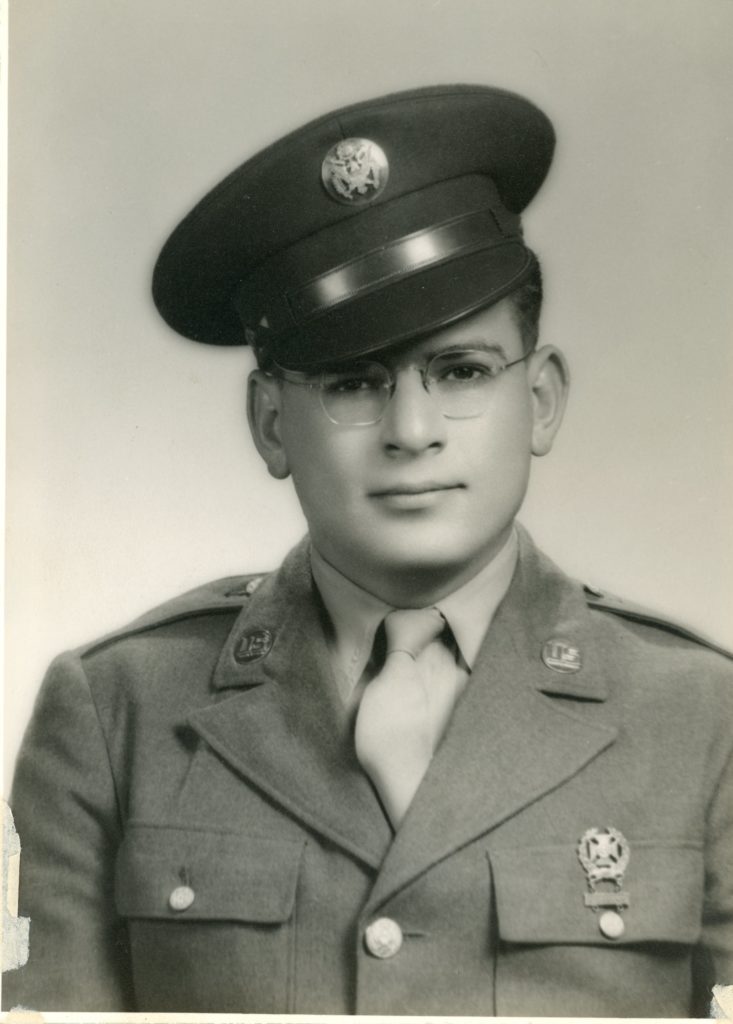

It was there that my father, Sam Kamlet, would have met L. G. Dad enlisted in the army on June 17, 1943, a day after graduating high school in Denver. He was 18 years old. He reported first to Camp Fannin, near Tyler, Texas, where he received his initial training. He was eventually enrolled in the Army Specialized Training Program—a course to train army personnel in technical fields such as engineering, dentistry, and medicine—and attended classes at Texas A&M in College Station. He had high hopes of becoming an engineer. Though he did well in his classes, the army abruptly ended the program. Dad found himself assigned in March 1944 to Company A, 409th Regiment of the 103rd Infantry, the “Cactus Division.” He packed his duffel bag for Camp Howze.

Like many veterans, Dad rarely spoke about his war experience. Whenever he was asked about it, he mostly deflected the question, saying it all seemed like a dream. Like it wasn’t real. He didn’t want to make a big deal out of it.

However, toward the end of his life, Dad agreed to discuss his experience in some detail, creating something of a memoir based on four different sources: a recorded conversation with my siblings and me; an interview conducted for the Library of Congress’s Veterans History Project; a brief, handwritten autobiography he produced at my insistence; and hundreds of letters he wrote home during the war. One thing that stands out is a singularly focused and consistent recollection of, and fondness for, Sergeant Allen. Whenever he spoke aloud about Allen, he would break down in tears, struggling to compose himself. It bordered on reverence.

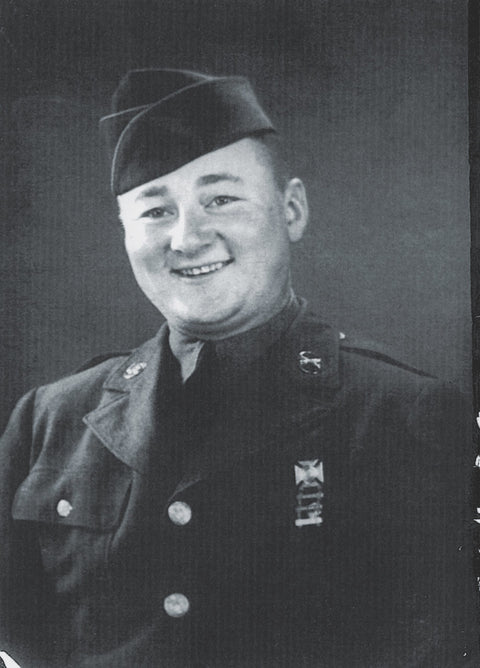

“One of the most remarkable people I met in the Army was my platoon sergeant whose name was ‘Dog’ Allen,” he wrote. “He was really tough on the outside but at heart a very feeling person. He was regular Army. He was a short, stocky guy and hard as nails.”

I cannot say for certain why the two men became friends. I regret never asking Dad before he died in 2008, but I have my theories. Dad was someone who respected authority and believed in the chain of command, so it was natural that he would respect his sergeant. Beyond that, it may be that because Allen was six years older, Dad saw him as something of a big brother.

Or perhaps the clue is in L. G.’s nickname: “Dog.” Maybe it wasn’t a casual choice, but rather reflected Allen’s true nature: steadfast, fiercely loyal, and protective. “You build relationships on trust,” Dad said. “And people like that, you think are invincible. And it’s not true.”

recorded for posterity

I HAVE SPENT MANY HOURS poring through the hundreds of letters that my father wrote during his year and a half in the army. Most were to my mother before they were married.

Many of his interactions with Allen that he wrote about were routine: requests for a pass into town; working hard to get through inspection; overnight hikes. And yet, by November 1944, it seemed that something of a brotherhood had been formed. On November 12, as their unit made preparations for shipping off to Europe, Dad wrote that he, Sergeant Allen, and the assistant squad leader had vowed “not to shave until we get our first German. I hardly expect to grow a very long beard,” he mused.

Their bravado was soon replaced by uncertainty. In that conversation with my siblings and me, Dad told us about the regiment’s arrival in Marseille, France: “When we first landed, before we went to the line, [Allen] went around with a little notebook [and got] our home addresses, and you know, who our next of kin were.” Dad went on to say, “And we were real dummies, [asking] ‘What are you doing that for, Dog?’” Allen answered, “Well, after this war is over, I’m going to come and sponge off of all of you guys.” Dad paused for a moment and added, “Well, that’s not what happened.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

The 409th had been in France only weeks when the soldiers were engaged in a battle to liberate the town of Sélestat in Alsace at the foot of the Vosges Mountains. The town was strategically important. Located just 11 miles from the German border, it sat at the junction of several major roads, including the Strasbourg-to-Colmar highway. The Germans had heavily fortified the town, placing machine gun nests to form an outer defensive ring. Roadblocks had been mined and were protected by snipers in nearby buildings.

Early on the morning of December 2, 1944, members of B Company had taken cover in a house in Sélestat when they came under heavy shelling from German tanks firing directly into the house, followed by concussion grenades. The Americans inside were trapped, their condition unknown.

The official citation issued in recognition of Sergeant Allen’s Silver Star explains what happened next: “Without further orders, [Allen] organized a squad for an advance on this enemy held position. He successfully located the house and finding three wounded soldiers, calmly prepared them for evacuation. Sergeant Allen then returned to his platoon and organized an assault on the enemy position. With utter disregard for his life he led his platoon forward, knowing that no communications were available to contact support in the rear. When pinned down by strong enemy fire, he placed his men in comparative safety. Then showing great devotion to duty, he fearlessly exposed himself to enemy fire in order that the source of the fire could be ascertained. Sergeant Allen was last seen gallantly carrying out this valiant task.” The citation concludes, “Throughout this action his conduct was in accordance with the highest traditions of military service.” Sélestat was liberated two days later.

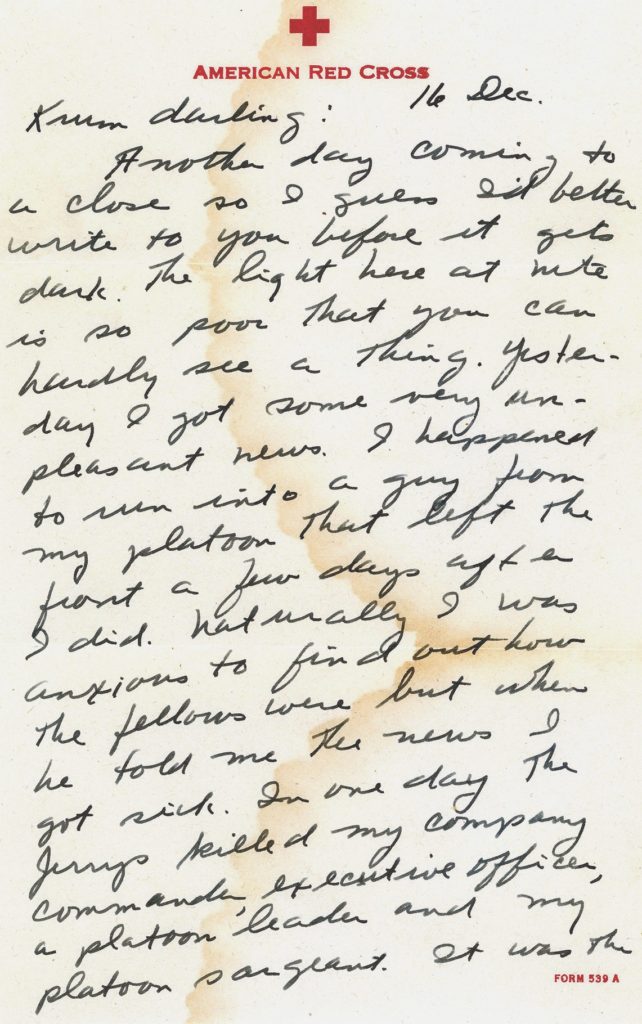

It’s possible my father would have been in that firefight, were it not for the fact that two days earlier he had suffered an ankle injury and was in a rear field hospital being treated. It was there he learned what had happened. In letters home to my grandparents and to my mother, my father wrote of his anguish. “I found a guy from my outfit here and he told me some very bad news. In one day, we lost four of our best men. The company commander, platoon leader, executive officer and my platoon sergeant. The sarge was really a swell guy…. It really hurt me to hear he was killed. He was the best soldier I ever knew and as fine a man as I ever want to know. There wasn’t a man in the entire company that wouldn’t go to hell for ‘Dog.’ I’ll miss him terribly and I’ll always remember him as a true friend and a real soldier.”

Dad’s sorrow then turned to anger. “After hearing something like that and then reading about the ridiculous things people back home are doing, it just makes a guy feel nauseated. Remember when I wrote you and said people back home were too optimistic? Well they still are. If they could only see the things I’ve seen in the little while I’ve been here, they would realize that this war isn’t a picnic and the G.I.’s here are going through a hell they will never be able to forget. But what’s the use of talking—America will still keep on dancing, wasting and having a big time and G.I.’s will still keep on going through hell. Gee honey, when I get started on something like that, I forget myself. I’m sorry but the sergeant’s death really hit me pretty hard.”

My father’s emotions were apparent once more when, on December 20, 1944, he wrote again to my mother from the hospital. “They had a retreat parade today to present the purple heart to some of the guys. I think it will be a long time before I feel the way I did today. Retreat is supposed to be a tribute to fallen comrades. Well, at this retreat I really had someone to pay tribute to and that was my platoon sergeant. When the bugler played The Star Spangled Banner I felt a chill run through me. Believe me a man gets to appreciate our flag and country after he’s away from it.”

Not long after, my father returned to his platoon, which was soon engaged in the Battle of the Bulge. He wrote more letters home, with mentions about guarding German POWs, helping a fellow soldier who had been partially paralyzed by enemy fire, and later being wounded himself. The bullet in his left shoulder ultimately led to his own return home, and his discharge. He was awarded a Purple Heart with an oak leaf cluster, a Combat and Expert Infantry Badge, and a European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with three bronze campaign stars.

Years later, we took Dad to see the National World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. He was overwhelmed with emotion. He stood by himself for the longest time, lost in his thoughts. In something of a symbolic reunion, both he and Sergeant Allen have been honored by having their names entered into the memorial registry.

A MAN TO REMEMBER

RECENTLY I TOOK A TRIP to Franklin to meet Sergeant Allen’s niece, Corinne Aiken. She was a two-year-old toddler when Allen enlisted in the army, and only seven when he was killed. She has no recollection of him. Corinne’s sister Carolyn, who is 18 months older, told me in a phone interview of her vague memories of the funeral service at the family home on Main Street in Franklin, and of going to the cemetery for the burial. Both women remember the gun salute, the playing of taps, and the flag that was taken from Allen’s casket, folded by the honor guard, and given to his mother, Minnie.

Corinne took me to visit his gravesite. For me it was an important milestone in my journey to learn more about him. His grave is marked by a simple headstone. As I expected, it is engraved with the name he preferred, “L G Allen.” It does not mention his Silver Star.

Corinne recalled that her grandmother, Allen’s mother Minnie, was overcome with grief after his death, as well as by the accidental drowning death of Allen’s sister in Franklin just six months after he was killed.

Both Corinne and Carolyn remember their grandmother, whom they called Mama, singing songs she had written about the deaths of her two children. The song about L. G. is sad and beautiful, expressing the love of a broken heart.

Come let’s go down by the ocean and sit in the moonlight

I’ve got a sad story to tell you and it must be told right.

I’ve got to go and serve my country, it is Uncle Sam’s demand.

I want to make a good soldier and do the best that I can.

We used to sit by the ocean and watch the tide come and go

Never dreamed our hearts would be broken,

our morale so sad and low.

Will you promise me my darling before I bid you adieu,

That you will always be faithful and find nobody new.

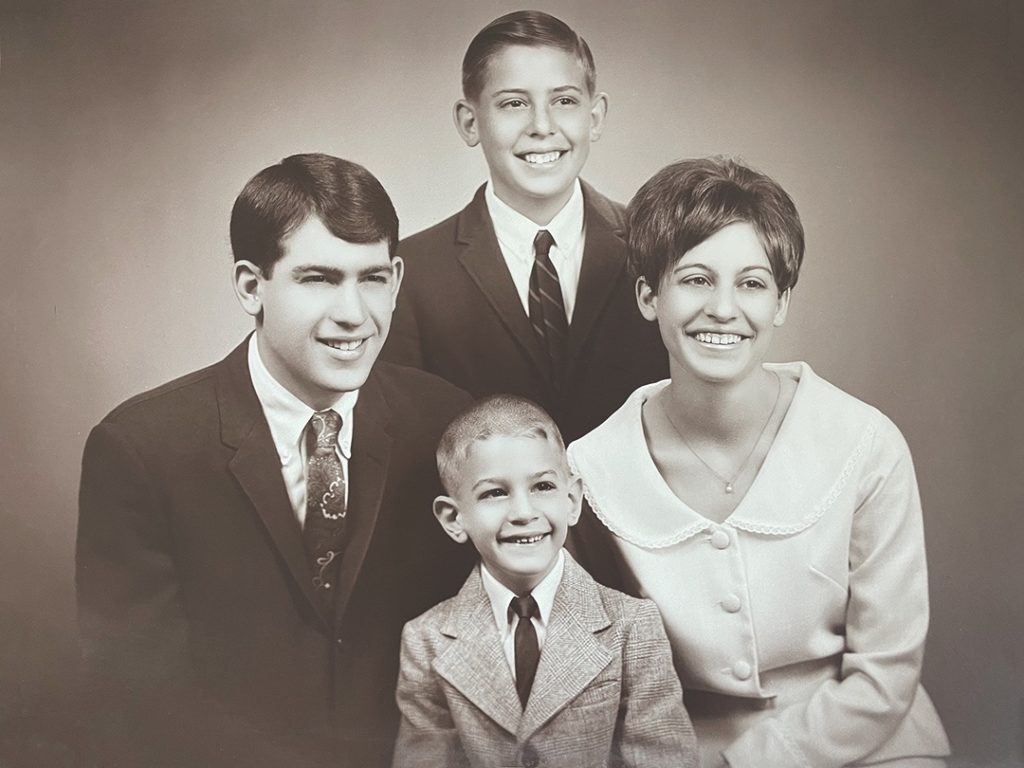

Just as Mama continued to mourn the loss of her son, so, too, did my father for his friend. In one of his last letters sent to my mother before he returned to the States, Dad wrote again about the man he admired. “I received a letter from you yesterday and you mentioned how pessimistic one of my letters had made you feel. That’s not what I intended to do but I guess my heart was full and I needed to pour some of it out somehow. Still, it is not often that one meets a man as fine as Sergeant Allen was. Frankly, I’d like to name one of our kids for him.”

I am that kid. Lee Gordon Kamlet.

Among my most treasured possessions are the flag that draped my father’s casket and a framed copy of Sergeant Allen’s Silver Star citation. They are priceless gifts from two men who played central roles in my life: one whom I love and admire, and one whom I admire and whose namesake I am privileged to be. Each has taught me the meaning of strength, courage, humility, and honor.

All photos courtesy of Lee G. Kamlet, except where noted.