How a Steamboat Saved a Confederate Army

On January 19, 1862, a Confederate army led by Brig. Gen. George B. Crittenden suffered a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Mill Springs. Fought in south- central Kentucky, the loss shattered the right flank of a defensive line that the Confederate army held across the southern half of the commonwealth. This Federal victory also led to additional military successes and helped consolidate Unionist control of the Bluegrass State at a critical time. Although the Union army sent the Confederates reeling, part of Crittenden’s command survived to fight another day. This was thanks to the small steamboat Noble Ellis , which carried Confederate soldiers across the Cumberland River after the battle. Like many of Crittenden’s troops, however, this vessel became a casualty of war.

That winter, Crittenden’s army was positioned at an entrenched camp at Beech Grove, Ky. Located approximately 20 miles from Somerset on the northern bank of the Cumberland River, the Confederate commander was unhappy with the site. Chosen by another officer, the location of the camp placed the Southerners’ backs against the water. “This river (greatly swollen), with high, muddy banks, was a troublesome barrier in the rear of Beech Grove,” Crittenden complained. “Transportation over it was, at best, very difficult. A small stern-wheel steamboat [the Noble Ellis ], unsuited for the transportation of horses, with two flat-boats, were the only means of crossing.” Although Crittenden bemoaned his logistical challenges, these small vessels eventually saved his army.

Crittenden, however, did not have time to redeploy. Union troops led by Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas, who were seeking to drive the Confederates from the region, soon advanced. Realizing it would be disastrous to defend poorly positioned and incomplete earthworks, Crittenden seized the initiative. He would leave camp and strike Thomas before reinforcements reached the Union army.

At midnight on January 18, Crittenden left Beech Grove to attack Thomas at Logan’s Crossroads, a small intersection ten miles to the north. It was a harrowing march. Sleet and rain churned the roads into deep mud, and it took the Confederates most of the night to reach their objective. Because of the rain, fog, and the troops’ inexperience, Crittenden kept his plan simple. His troops would advance northward up the Mill Springs road, toward Logan’s Crossroads. When they encountered the enemy, his regiments would deploy on either side of the lane and attack, using the road as their guide.

Major General George H. Thomas’ troops

overwhelm Confederate troops at the Battle of Mill Springs. His victory helped

the Union maintain a hold on Eastern Kentucky.

At daylight on January 19, the Confederate advance encountered Union pickets from the 1st Kentucky Cavalry. After some sporadic gunfire, the loyalist Kentuckians fell back to the 10th Indiana Infantry, who were posted in support a mile up the road.

The poor weather, mud, and limited visibility led to a piecemeal Southern assault. The 19th Tennessee and 15th Mississippi infantry regiments struck the 10th Indiana and the dismounted 1st Kentucky Cavalry near a fence located south of Logan’s Crossroads. After nearly an hour, the 4th Kentucky Infantry (U.S.A.) reinforced the Federal left flank along the fence. There, they battled the Mississippians and the 20th Tennessee Infantry. One Union soldier later recalled the severity of the fight, noting that “trees were flecked with bullets, underbrush cut away as with a scythe. Dead and wounded lay along the fence, on the one side the Blue on the other the Gray; enemy dead were everywhere scattered across the open field.”

Fog and lingering black powder smoke hindered visibility and fractured unit cohesion. Moreover, as a steady rain fell, many of the Southerners’ antiquated flintlock muskets became wet and failed to fire. The poor visibility soon had more disastrous consequences. At the height of the action, Confederate Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer, who led half of Crittenden’s army, accidentally wandered too close to the Union lines. Members of the 4th Kentucky Infantry shot him down. Confederate cavalryman R.R. Hancock later said, “the fall of our gallant leader was a desperate blow to the followers.”

Shortly after Zollicoffer’s death, Thomas arrived on the field. The Union commander quickly deployed the 2nd Minnesota at the fence to replace the weary 4th Kentucky. He then sent a brigade of Unionist East Tennesseans and Kentuckians to drive the Confederates out of a ravine on his extreme left flank. The 9th Ohio Infantry, a unit comprised of German immigrants from Cincinnati, then led a bayonet charge that shattered the Confederate left. Soon, other Union soldiers joined the charge, and the Rebel army fled back to their camp on the river. According to one Union colonel, “the whole [Confederate] line gave way in great confusion, and the whole turned into a perfect rout.”

A life lost, a career damaged: Felix Kirk

Zollicoffer, left, was killed when he mistook Union troops to be his own men,

and rode too close to their lines. Colonel Speed Fry of the 4th Kentucky

(U.S.) took credit for shooting him. The defeat at Mill Springs drove Maj.

Gen. George Crittenden, right, out of field service.

The Federals had approximately 4,000 men on the field while the Rebels had about 5,500 troops. It was reported that the Union army lost 39 killed and 207 wounded, and that the Confederates suffered 125 killed, 308 wounded, and 95 missing.

When Crittenden’s troops straggled back into their entrenchments, it was clear that they were in an untenable position. There were few provisions, and the fortifications were deficient. Furthermore, Union artillery deployed on high ground above the camp and shelled the Confederate works. With disaster looming, Crittenden ordered his men to escape across the swollen Cumberland River.

The attempt would have been impossible were it not for the small stern-wheeled steamboat, Noble Ellis. Built in 1860, it was named in honor of Noble D. Ellis, a Tennessee politician and co-owner of a Nashville iron foundry that manufactured everything from window sash weights to bank vaults and water wheels. Before the war, Noble Ellis ran a regular route on the Tennessee River, carrying freight between Nashville and Paducah, Ky. Good hauls made the news. In September 1860, for example, the Nashville Republican Banner reported that the Noble Ellis and another steamboat had arrived “from Paducah with a cargo of sundry articles.” Within months, the steamboat saved hundreds of Confederates at Beech Grove.

Fortunately for the Rebels, Crittenden found a capable captain for Noble Ellis. When the Confederate commander gave the order to abandon camp, C.C. Spiller, a member of the 4th Tennessee Cavalry who was also an experienced steamboat pilot, traded his spurs for a steam engine. Spiller hauled scores of soldiers across the river on the Noble Ellis with the two barges in tow. Because it was a small vessel, the army abandoned most of their equipment. Crittenden reported that “Many cavalry horses, artillery horses, mules, wagons, and eleven pieces of artillery, with baggage and camp and garrison equipage were left behind.”

Crittenden, however, was more concerned about the survival of Noble Ellis. When Union artillery shelled the camp, they also fired “a shot or two over the boat.” When darkness fell, the Union gunners ceased fire. They would wait until daylight to destroy the vessel. Crittenden knew that it was imperative for his troops to cross before morning. “The steamboat destroyed, the crossing of the river would have been impossible,” Crittenden explained. Therefore, that night, Noble Ellis rushed to transport the Confederate army across the water.

Within the Rebel works, the scene was chaotic. “We are on the river bank in one compact mass of excited and confused humanity,” a member of the 19th Tennessee related. “Thousands were crowded there waiting, each his turn to get on the Noble Ellis as she crossed and recrossed the river….What a racket and confusion reigned here, and right in the face of the enemy.”

As soldiers crowded on the vessels, dozens of other troops tried to swim across the river. Many were swept away by the fast current. Drowned men were later found downstream, which led Union Colonel Mahlon Manson and several newspapers to report that several hundred Southerners had died in the water. Confederate Brigadier General William H. Carroll confirmed the rumor, noting that as cavalrymen tried to swim their horses across, “many were drowned in the attempt.” Within six hours, however, most of the Rebel command had crossed safely.

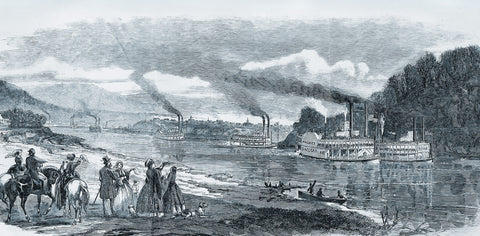

Not all river steamboats were glamorous, large

affairs. No image of Crittenden’s savior Noble Ellis exists, but it would have

been a smaller vessel, like this picket boat with an exposed boiler sketched

on Florida’s St. John’s River.

When the Union artillerymen returned to their guns at daybreak, Noble Ellis was steaming the last soldiers across the water. The gunners fired smoothbore artillery at the boat, but the shells fell short. They had better luck with two Parrott Rifles. According to the New York Times , one shot went through the vessel’s chimney while another “exploded over the wheel.” Union gunner Joseph Durfee wrote that “we saw a steamer just crossing the river. We fired at her with the Parrott guns, and after firing ten shots, set her on fire….When we shelled her, she was loaded with horses and baggage. The horses jumped overboard, some were saved and some drowned.” A reporter on the scene remarked, “It is uncertain whether the steamboat was fired by our shells or destroyed by the rebels. The conflagration was watched from the hills by our men while ‘bombs bursting in air,’ lent a terrible reality to the scene.”

While multiple Union correspondents said that Federal artillery ignited Noble Ellis , Crittenden later reported that the captain of the vessel had torched the boat. “Much is due to the energy, skill, and courage of Captain Spiller, of the cavalry, who commanded the boat, and continued crossing over with it until fired upon by the enemy in the morning, when he burned it by my directions,” Crittenden wrote. The Confederate commander did not want the steamer to fall into Union hands. At least one Northern soldier understood, writing, “I think it an error about our destroying the steamboat, but that the rebels had crossed and set it on fire on leaving it.”

Upon realizing that Crittenden’s army had escaped, Thomas’ troops entered the camp. They were surprised that the Confederates had abandoned so much property. “The enemy having crossed the river during the night, or early in the morning, the rout was complete,” one witness contended. “It seems as though there was a perfect panic among them, their tents having been left standing, and their blankets, clothes, cooking utensils, letters, papers, etc., all left behind. Here were all, or nearly all of their wagons, some twelve or fifteen hundred horses and mules, harnesses, saddles, sabres, guns; in fact, everything. It was a complete stampede, and by far the most disastrous defeat the Southern Confederacy has yet met with. Ten pieces of cannon, with caissons, are also here. To all appearances, they seem to have completely lost their senses, having only one object in view, and that was to run somewhere and hide themselves.”

In addition to weapons and animals, the cache included sugar, rice, coffee, bacon, pork, potatoes, soap, candles, letters, watches, and tobacco. Thomas was elated, telling his superiors that “the enemy had abandoned everything and retired during the night.” Colonel Manson added that, “The panic among them was so great that they even left a number of their sick and wounded in a dying state upon the river bank.”

George Thomas

Although Thomas was thrilled to have driven Crittenden away, he regretted his inability to chase the Confederate army. “The steam and ferry boats having been burned by the enemy in their retreat, it was found impossible to cross the river and pursue them,” Thomas reported. Union Colonel John Marshall Harlan of the 10th Kentucky Infantry concurred. Harlan wrote, “Further pursuit was impossible, since the rebels in their retreat had utterly destroyed or removed all means of crossing the river.” The Noble Ellis had saved the Confederate army, and its destruction blunted the Federal pursuit.

Crittenden’s army had escaped, yet they were in a precarious position. One Union soldier wrote his brother that, “I learn one of their steamboats, which was carrying them across the river, was shot into and fired by our artillery, destroying all in it in toto.” He added, “After crossing the river the rebels did not stop, but ran like devils.” The day after the battle, a member of the 15th Mississippi Infantry informed his family that “they whipped us by overwhelming numbers. We burned our steamboat, destroyed our boats, and are trying to rally. The Gen. is doing everything to save his command.” That command was fractured, but thousands had been saved thanks to Noble Ellis.

Although the steamboat had ensured Crittenden’s escape, Unionists were still elated. One called the Battle of Mill Springs “a great victory on our side,” while a Unionist Kentuckian said it was “the first blow which breaks the back of this rebellion.” Thanks to the Federal victory at Mill Springs, Confederate troops were ultimately driven from the Bluegrass State. It also began a chain reaction; in February, Fort Henry and Fort Donelson surrendered. Nashville then fell to Union forces. By the end of March 1862, the Confederates had withdrawn to Corinth, Miss. One Union soldier wrote home, “I think we have more than paid them up for Bull Run….Their army is perfectly destroyed and demoralized.” Yet, they would have been annihilated were it not for Noble Ellis.

Stuart W. Sanders is the author of four books, including The Battle of Mill Springs, Kentucky . His latest, Murder on the Ohio Belle , examines antebellum violence, Southern honor culture, vigilante justice, and the Civil War though the lens of an 1856 murder on a steamboat.