How a 17-Year-Old New Yorker Became the First Jewish Medal of Honor Recipient

"He is a frequent and faithful and capable officer in the civil service, but he is charged with an unpatriotic disinclination to stand by the flag as a soldier, like the Christian Quaker.” So wrote Mark Twain in Harper ’s magazine in 1897, reflecting a virtually worldwide stereotype of his time and all too often still believed today. In contrast to his contemporaries, however, Twain was not averse to publicly admitting how wrong he was just a year later. Having more closely checked the “statistics,” he discovered that Jews had taken up arms for the United States since the Revolution. As to an “unpatriotic disinclination to stand by the flag as a soldier,” Twain could have kept his foot out of his mouth had he checked the Civil War career of Pvt. Benjamin Levy.

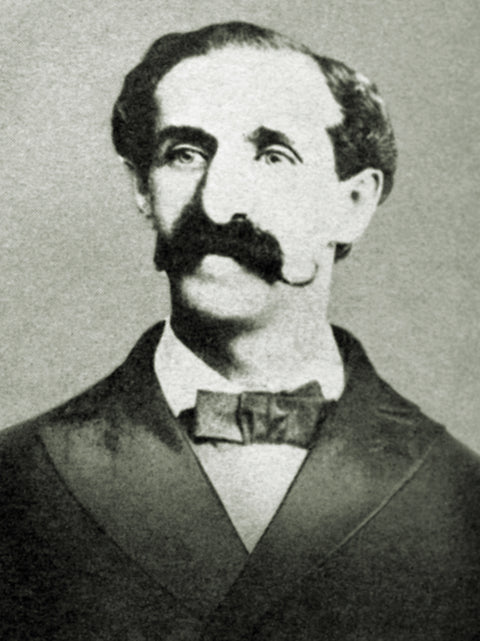

Aside from being born in Brooklyn, New York on Feb. 22, 1845, little or nothing is known of Benjamin Bennett Levy’s prewar schooling or employment. The only known photograph of him was taken years after the war, but confirm descriptions of his being a small, scrawny individual. What is recorded is that he enlisted in the Union Army on April 22, 1861, just days after war broke out.

Commended by Two Generals

Not yet 17 years of age, he was assigned to Company G of the 1st New York Infantry Regiment of Volunteers as a drummer boy. Commanded by Col. Garret W. Dyckman, the 1st N.Y. was then part of the 1st Brigade, 1st Division, Department of Virginia. It may be added that Ben’s younger brother, Robert, also enlisted and was likewise assigned as a drummer boy to the 7th New York Infantry.

October saw the 1st New York in Newport News, Virginia. Besides his regular training, Pvt. Levy spent some of his time there assigned as an orderly to Brig. Gen. Joseph King Fenno Mansfield. In February 1862, Levy was carrying dispatches from Mansfield to Maj. Gen. John E. Wool at Fort Monroe aboard the steamboat Express when the vessel came under attack near Norfolk by CSS Sea Bird , a sidewheeler seized by the Confederates, armed with a 32-pounder smoothbore cannon and a 30-pounder rifle and made the flagship of the small but aggressive “Mosquito Fleet” harassing the Union coastal blockade. Express was unarmed and towing a water schooner, whose weight and drag clearly favored the enemy gunboat’s prospects of overhauling its prey.

This battle flag carried by the 1st Regiment of the New York

Volunteer Infantry shows the U.S. national pattern as prescribed by the U.S.

Army in January 1862. Levy saved the regimental flags from being captured and

used them to rally fellow New York troops against Confederate forces. Levy was

awarded the Medal of Honor in 1865.

Swiftly assessing the situation, Levy cut the schooner loose. This resulted in its capture by the Rebels, but gave Express the extra knots it needed to outrun its pursuer. After its safe arrival at Fort Monroe, Levy was commended by both generals Mansfield and Wool for his quick-thinking initiative. CSS Sea Bird did not last much longer—after participating in the unsuccessful defense of Roanoke Island from Feb. 7–8, it was rammed and sunk by the Union warship Commodore Perry off Elizabeth City, North Carolina on the 10th.

Levy subsequently returned to the 1st New York, which on June 6, 1862 was attached to Brig. Gen. Hiram G. Berry’s 3rd Brigade, Brig. Gen. Philip Kearny’s 3rd Division, Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman’s 2nd Corps of the Army of the Potomac. Under the overall command of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the army marched up the Virginia Peninsula to seize the Confederate capital of Richmond—which would have been a brilliant lightning stroke if only McClellan hadn’t executed it at a snail’s pace.

Caught Up in the Seven Days Campaign

As Confederate forces resisted the Army of the Potomac’s slow but seemingly inexorable advance, they lost two generals in quick succession: Joseph E. Johnston, wounded at Seven Pines (aka Fair Oaks) on May 31, and the ailing Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith, who proved too indecisive to lead the army. With nobody else available at that point, Confederate President Jefferson Davis placed his military adviser, Gen. Robert E. Lee, in charge of Richmond’s defenders, who Lee reorganized into what became the Army of Northern Virginia.

Recommended for you

Benefiting from a wealth of talented subordinates, Lee suddenly took the offensive at Gaines’ Mill on June 27, defeating the Union 5th Corps and initiating a week of battles which, while costly and sometimes ending in tactical defeat, wrested the initiative from McClellan and drove his army back down the Peninsula.

The penultimate battle of Lee’s Seven Days campaign centered on Glendale Crossroads (also called Frayser’s Farm). McClellan’s army had to pass through it to reach the relative safety of Harrison’s Landing on the James River, where U.S. Navy ships and vitally needed supplies awaited. With the opportunity to cut off the Army of the Potomac from its base and split it in two, Lee devised a complex plan to launch attacks to the north and south of Glendale, to be followed by a final blow to the Union center. With a demoralized McClellan agonizing aboard the ironclad warship USS Galena , the Army of the Potomac’s fate lay in the hands of his field officers and individual soldiers fighting for survival.

Among them was Pvt. Levy, whose regiment was then on the right (northern) flank when it faced an onslaught by elements of Brig. Gen. Roger A. Pryor’s 5th Brigade of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s Division at 3:30 p.m. This was just a small element of Lee’s effort to trap the Army of the Potomac, with Longstreet’s and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill’s divisions advancing north and south of the Long Bridge Road to seize Frayser’s Farm, in the process of which they crashed into the 5th Corps’ Pennsylvania Reserve Division under Brig. Gen. George A. McCall.

A Broken Drum And the Death of A Friend

Although Brigadier Generals Phil Kearny, Joseph Hooker and John Sedgwick launched counterattacks to support them, the Pennsylvania Reserves were routed and McCall, taken prisoner. The Confederates pressed on to cut off the Union southward retreat route along the Willis Church Road.

Levy’s drum was destroyed in the course of the afternoon’s fighting. He retired to a tent at Charles City Crossroads, assisting the company surgeon, as was the standard secondary role played by the Musician Corps. While there, he came upon a tentmate, Jacob Turnbull, suffering with malaria, just as the sound of gunfire in his sector was reaching a crescendo.

Snatching up Turnbull’s rifle and equipment, Levy rushed off to join his comrades in the line. Just as the 1st New York launched a countercharge, he saw another friend holding the regimental colors, Charley Mahorn, suddenly fall, shot in the chest.

In a war dominated by line infantry, each firing a single-shot rifle musket, the unit flag was, as much as the drum or the bugle, an essential means of communication. The rifles were most effectively used if fired all at once, essentially constituting a horizontal shotgun. To form the line, the company literally “rallied ‘round the flag.” Beyond that, the battle flag was an object of unit pride, whose presence or absence in the field affected morale.

Rallying Men To The Flag

Company G lost cohesion and was in danger of breaking and running in the face of a Confederate attack. Realizing that, Levy ran over, recovered the flag and, waving it and shouting amid the pandemonium, rallied the wavering New Yorkers, whose restored line checked the enemy advance. The unit then conducted a fighting retreat, during which Levy spotted another flag on the ground and recovered that as well. As the 1st New York emerged from the tree line, Brig. Gen. Kearny noticed Levy carrying a flag on either shoulder. Heartily commending him, he promoted Levy to color sergeant on the spot.

Thanks to its soldiers’ collective efforts, the battered Army of the Potomac escaped Lee’s trap and retired south along the Willis Church Road to Malvern Hill. Although inconclusive, the Battle of Glendale had been a bloody affair, with 3,673 Confederate and 3,797 Union casualties representing the wide range of ranks involved, from Sgt.Levy, who was slightly wounded, to his corps commander, Heintzelman, who was badly bruised in the left wrist by a spent bullet and unable to use it for several weeks.

This map shows the Battle of Glendale which took place on

June 30, 1862, in which Levy demonstrated heroism in retrieving two battle

flags and managing to hold the line against a Confederate advance. Brig. Gen.

Kearny promoted Levy to color sergeant immediately as he saw him victoriously

carrying the battle flags on his shoulders.

The next day, July 1, saw Lee’s last bid to maul the Army of the Potomac at Malvern Hill, but this time Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter had installed his 5th Corps on the high ground, backed by 171 guns and three nearby warships, against which Lee hurled three assaults with inadequate artillery support. The result was a disastrous 5,650 Confederate casualties compared to some 3,000 Union.

At one point, however, the wind and dust gave the 1st New York’s uniforms such a grayish patina that some of the Union guns began firing on its position. In response, Col. Dyckman ordered Levy to advance on the field and unfurl the colors. That identified the regiment to the artillery, but it also attracted Confederate sharpshooters who put several bullet holes in the flagstaff and in Levy’s equipment but miraculously missed him.

Levy Re-Enlists

Malvern Hill ended the Seven Days battles with a stinging tactical defeat for Lee, but McClellan’s only follow-up was to continue his retreat, ending his Peninsula Campaign with Lee the strategic victor. For almost three years thereafter the eastern United States was bathed in blood as the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia battled it out.

Levy served through this succession of campaigns until May 1863, when the 1st New York’s term of service expired. He was among the troops mustered out. Levy seems to have been unable to accept a life of relative peace amid an ongoing war. On Jan. 18, 1864, he re-enlisted in Company E, 40th New York Volunteer Infantry, with the rank of private.

The 40th New York was attached to the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, 2nd Corps, Army of the Potomac. Although the army’s latest commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, had won a resounding victory at Gettysburg in July 1863, Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia remained a force to be reckoned with.

In March 1864, however, the Union Army got an aggressive new commander in chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. And in late April Grant launched a multi- pronged offensive against the Confederacy in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, in Georgia and in eastern Virginia. Seeking battle with the Army of Northern Virginia, the Army of the Potomac was officially led by Meade, but Grant, accompanying him, would truly lead the campaign.

The grave marker of Sgt.

Benjamin Levy honors his Civil War service, Jewish heritage and the Medal of

Honor he received for his heroism. He is one of at least five Jews to have

received the medal during the Civil War.

On May 5, 1864 the Army of the Potomac was marching through the Wilderness when it was intercepted by its Southern nemesis. On roughly the same ground where he had defeated it in the Battle of Chancellorsville a year ago, Lee hoped to repeat history. Late that morning Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s 2nd Corps, including the 40th New York, moved down the Orange Plank Road. The formation behind it, Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 6th Corps, was attacked by Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division of Lt. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill’s 3rd Corps. Hancock pulled back to assist Sedgwick, while Hill reinforced Heth with Maj. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s division.

Wounded in Battle

In the fiery exchange of ordnance that followed, Levy became one of 213 casualties suffered by the 40th New York in the battle when a Rebel bullet inflicted a compound fracture on his left thigh. The Battle of the Wilderness ended on May 6 in a narrow tactical victory for Lee. But unlike Chancellorsville, which ended with Maj. Gen. “Fighting Joe” Hooker ordering the Army of the Potomac to retreat, Grant spread the word that the army was to resume its march on Richmond—an order that dictated the entire course of the campaign to its ultimate conclusion on April 9, 1865 with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House.

At the end of the war the 40th New York recorded the deaths of 10 officers and 228 enlisted men killed in action. Two officers and 170 succumbed to disease. Its unit history includes: “Sergeant Levy, Benjamin, age 19 years, enlisted at Eighth District New York, to serve three years, and mustered in as private, Co. E, January 18, 1864; wounded in action, May 5, 1864, at the Wilderness, Va., letter of company changed to B, July 7, 1864; discharged for disability, May 31, 1865, at Washington, D.C.; prior service in First Infantry; veteran.”

What the 40th New York overlooked in its chronology was that on March 1, 1865, Levy was awarded the Medal of Honor with the following citation: “This soldier, a drummer boy, took the gun of a sick comrade, went into the fight, and when the color bearers were shot down, carried the colors and saved them from capture.” Details of his postwar civilian activities are unknown.

Levy was 76 when he died on July 20, 1921 and was buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn. There is also a historical marker in Henrico County, near Richmond, in the approximate place where he became the first Jewish American to receive the Medal of Honor. At least five other Jews are known to have received the medal during the Civil War and many more would follow thereafter.