History of the Condom: Why It’s Still the Only Contraception for Men

While scholars argue about the murky origins of the word “condom” — first documented in print in English as “condum” around 1706 — nobody disputes that it is the oldest and most widely adopted birth control device.

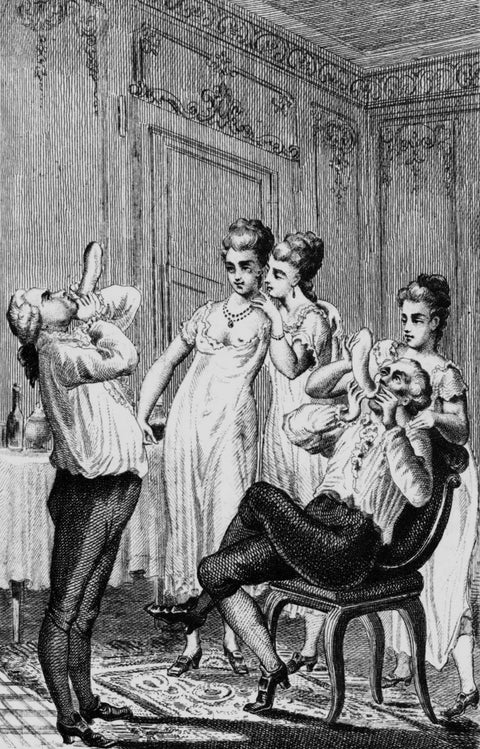

The earliest known condoms, made from animal intestines, were thick and reusable. Later varieties were made from oiled silk, linen, thin leather and fish-bladder ($5 for a dozen in New York City in 1860). All had flaws: uncomfortable seams, fragility or pleasure-sapping thickness. More recently, inventors have dabbled in products that block the release of sperm, either through hormonal or mechanical disruption. None has reached the market, although you will see that they have come tantalizingly close.

The barrier provided by even rudimentary condoms remains the only device available to men — and even then, it’s a not-so-reliable barrier, thanks to imperfect usage and breakage. Roughly 13% of couples that rely on condoms alone for birth control will become pregnant in a year. For much of U.S. history, the condom existed in the underworld, regarded as an accessory to vice and loose morals. The story of its widespread adoption coincides with industrialization in the United States, military mobilization in the world wars and the growing hazard of sexually transmitted disease.

Condoms for the People

Long a product for those wealthy enough to afford them, condoms reached a mass market only with the discovery of how to make rubber more useful and durable. That method, known as vulcanization, was the brainchild of Charles Goodyear, a star-crossed, tenacious manufacturer and inventor in New Haven, Connecticut.

Goodrich discovered in 1839 how to treat the sap from rubber trees with sulfur and white lead, at a high temperature so that it became non-adhesive, durable and flexible. He patented the technique in 1844 and got wrapped up — and defeated — in a suit against inventors in England who had figured out his technique. He died in debt in 1860, during a visit to his dying daughter. Goodyear never benefited commercially from his astounding discovery, although his family later received royalties.

While rubber tires are the best-known application of vulcanized rubber, it was also used to make condoms (and even before that, other contraceptive devices such as diaphragms and cervical caps). By 1889, a seamless rubber condom was being sold.

GET HISTORY 'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit

Crusaders Against Condoms

But it wasn’t sold in the mainstream. Anti-vice warrior Anthony Comstock had promoted legislation in 1873 that criminalized dissemination of birth control information and products, so buyers found them marketed under such euphemisms as “French male safes,” “gentlemen’s protectors” and “the English letter.”

A boutique business of making condoms, mostly a home-based enterprise, sprang up. The leader in the field was an immigrant in New York City, Julius Schmid, who had come from Germany to the United States as a penniless but resourceful teenager with a disability. While working in a sausage factory, Schmid put surplus intestinal casing to use making condoms in 1883. Schmid would later adopt Goodyear’s innovation and the company he founded would become the leading manufacturer of both rubber and “skin”-based condoms under the brands Ramses and Sheik.

Soldiers and Venereal Disease

Rampant venereal disease among young soldiers during a crisis on the U.S.-Mexican border in 1916 and during deployments for World War I would provoke an attitude more tolerant of condom use, if only to prevent the men from infection, and not the woman from pregnancy. Recruitment in World War I had exposed the widespread prevalence of venereal disease among young American men — in some areas, a third of the recruits were found to have venereal disease acquired before service. Opportunities only increased in military settings where young men assembled without family or spouses.

Sexually transmitted diseases spread easily during military campaigns. A horrific example is how syphilis swept across Europe following the campaign in 1494 of French monarch Charles VIII in Italy. Mercenaries fighting in the conflict from other regions carried the pathogen home, furthering the spread. In the case of the American Civil War, some 100,000 cases of gonorrhea were reported over two years in the Union Army . But venereal disease flourishes in peacetime, too. By 1904, venereal infection ranked as one of the top four reasons applicants to the U.S. military were rejected.

During World War I, American allies in France and Germany furnished soldiers with condoms and regulated brothels, but U.S. military leaders instead admonished soldiers to refrain from sex and required soldiers to arrange to be treated for “disinfection” after sexual activity. This involved cleansing the penis with a mercury solution, then injecting another substance into the urethra, followed by a coating of calomel on the penis. By Gen. John Pershing’s General Order No. 6, issued in July 1917, soldiers were to report for this treatment within three hours of sexual activity. Men who contracted venereal disease through what was deemed “neglect” would be subject to court-martial. This mandated treatment was never proven to be effective against the disease, although it may have curtailed sexual activity.

Out of roughly 3 million U.S. soldiers in World War I, there were about 415,000 cases of venereal disease, and about 100,000 were discharged for that reason. That adds up to about 7.5 million days devoted to care in hospital. It has been calculated to equal 21,000 soldiers missing for an entire year — equivalent to two infantry brigades. **** Andrea Tone, author of “Devices and Desires: A History of Contraception in America,” notes that, by the end of World War I, the United States had spent more than $50 million to treat sexually transmitted disease in soldiers. However, effective treatments for gonorrhea and syphilis were not available until 1937 and 1943, respectively.

By then condoms had gained a modicum of public acceptance. In 1930, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit had ruled that although condoms were illegal when promoted for “illicit sexual intercourse,” they were legal when they were purchased to prevent disease. This expanded the marketing options. Makers could now sell them across state lines.

Putting Out the Factory Fire ****

A technological breakthrough also came in 1930. A design by Fred Killian of Akron, Ohio, in 1930 enabled the creation of a condom assembly line that didn’t rely on human workers and could produce 800 condoms a day. Killian’s invention used latex instead of rubber, thus reducing the fire hazard that had plagued rubber condom production, which involved highly flammable ingredients for processing raw rubber. However, the machine cost $20,000 and came with hefty royalty fees, limiting entry for small-time manufacturers. By 1931, the top 15 manufacturers were making 1.44 million condoms a day.

When the United States entered World War II, soldiers could expect to have condoms available for purchase. According to Tone, **** condom production capacity doubled between 1939 and 1946. The addition of latex to the ingredient mix, along with production standards from the Food and Drug Administration, improved quality control.

The Army bluntly recognized the importance: “The condom affords the only practical protection against venereal infection. Post exchanges are required to stock condoms of approved quality. A condom will prevent gonorrheal infection which must enter the urethra."

Recommended for you

But accessibility doesn’t ensure compliance. One researcher claims that a GI in Europe during World War II had on average slept with 25 women — and frequently without condoms. Meanwhile, soldiers found other uses for condoms: as an ersatz surgical glove and water vessel, as well as a covering to keep a rifle clean.

Postwar, many Americans adopted condoms. But the birth-control pill, which altered a woman’s fertility hormonally, took off after 1965, along with intra- uterine devices, or IUDs. While 42% of Americans relied on condoms for birth control from 1955 to 1965, one source says that Americans were twice as likely to use the Pill as they were the condom in 1968.

However, condoms remained popular for casual sexual encounters or for those who preferred nonhormonal methods of birth control. And condoms became a mainstay for preventing HIV infection. Today, condoms are made with blends of rubber, latex and often other chemicals. The condom is a many-splendored thing, available in colors and flavors and textures, and often laden with spermicide.

Modern Male Birth Control

For decades, researchers have been looking for a male-centered pill that interrupts sperm production. Many efforts involve targeting one or more of the hormones involved in sperm production. One approach involves a monthly injection; another involves a cream applied to the shoulders daily. What researchers confront with these products is a regulatory standard requiring that the products must cause no harm. While women’s birth control products, such as the pill or the IUD, have side effects and risks, so does giving birth. That is why regulators accept risks for products related to women’s birth control. However, because men are not at risk for the hazards that accompany pregnancy and giving birth, contraceptives for men must be risk- free, as regulators are not inclined to approve products that impose an otherwise avoidable risk.

A story from the 1950s about this hazard involves a drug being tested in mice to control parasitic worms. The effect wasn’t what researchers hoped for, but they noticed that the mice given the substance weren’t reproducing. Indeed, their sperm counts had plunged, but no adverse effects were noted. When the researchers tested the drug among inmates at a prison near Salem, Oregon, they found that men taking the substance had drastically reduced sperm counts without adverse side effects. That is, not until one of the participants enjoyed some whiskey snuck into the prison. Or tried to enjoy: He immediately felt horribly sick. Ultimately, it turned out the drug being tested affected enzymes that function in both sperm production and alcohol metabolism. That put a stop to that substance as a risk-free birth control drug.

Another remarkable story involves the discovery of a sperm-crippling substance by an inventor in Kharagpur, India, who had developed a bactericidal compound to apply to water pipes. A professor, Sujoy K. Guha, was working out how to provide clean water in rural India, and in 1979 realized that the plumbing of men’s sperm-producing apparatus might be similarly targeted. A substance, a common polymer called styrene maleic anhydride, when injected in the vas deferens (the sperm-bearing connection to the urethra) would disable movement of a sperm’s tail, preventing transport to the egg. Moreover, the material could be easily dissolved after insertion, restoring normal sperm production. The contraceptive, known as RISUG (reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance) has been tested in India, both in animals and in ongoing clinical trials in men.

It may also prove to be an option for blocking egg transport in a woman’s fallopian tubes. Another possible contraceptive is the Shug, which consists of silicon plugs inserted into the vas deferens to block sperm movement, but it has not advanced to the market.

What is stymying further development is money — the cost of large clinical trials proving efficacy and safety, along with the reluctance of large pharmaceutical firms to create a low-cost product that could threaten the profits gained from selling various forms of the Pill and other female contraceptive devices. For now, it is a David and Goliath fight to bring new methods for male contraceptives to market. The Male Contraceptive Initiative, founded in 2013 as the Foundation for Male Contraception, funds investigators. Most focus on hormonal approaches. However, Revolution Contraceptives, a project begun by the MCI founder, is working on finding a partner with pockets deep enough to bring Vasalgel, a product based on the RISUG model, to production in the United States.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.