He Trained Behind Cannons. Then They Sent Him to the Front Lines.

Among the 28 regiments raised in New York as a result of President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 300,000 volunteers on July 1, 1862, was Colonel Joseph Welling’s 138th New York Volunteer Infantry, a regiment that was re-designated the 9th New York Heavy Artillery on December 9, 1862. Among those who answered Lincoln’s appeal and joined Welling’s regiment was Lewis Foster.

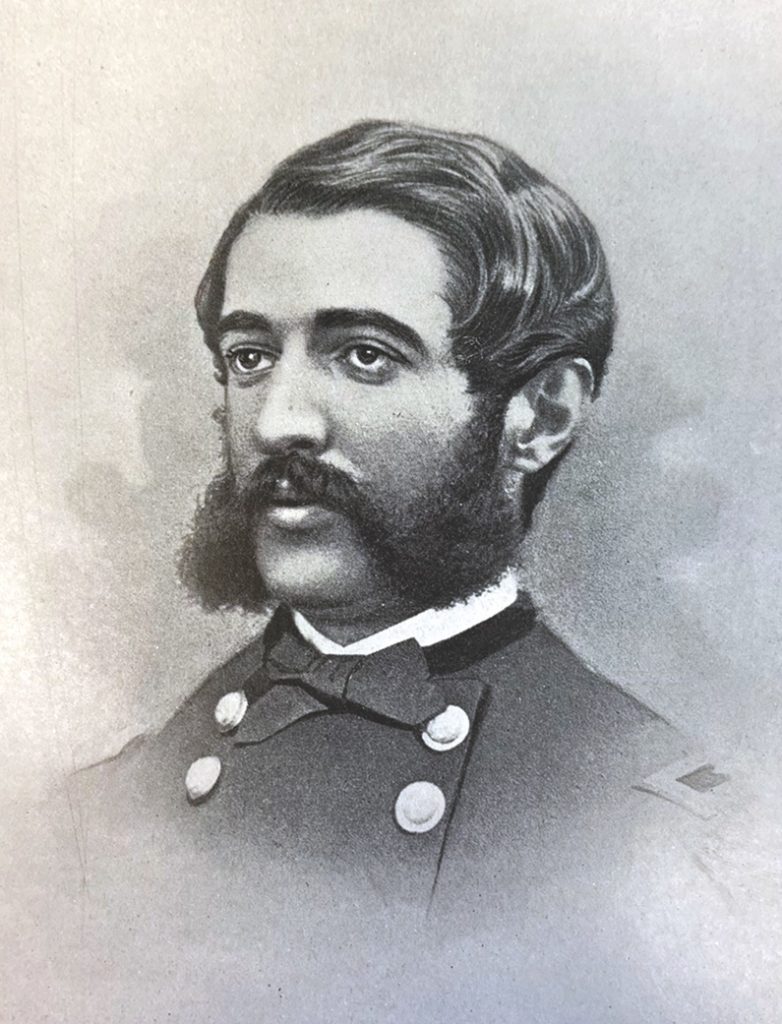

Foster stated his age as 18 at the time of his enlistment in Company C on September 1, 1862, but in actuality he had turned 16 just four days before. Promoted to corporal on November 14, 1864, the resident of Wayne County, N.Y., served for the war’s duration with the 9th New York.

On September 12, 1862, following a brief period of training, Foster and his comrades departed for Washington, D.C. Five days later they arrived in the nation’s capital. From that moment until May 18, 1864, the regiment served in Washington’s defenses. After that, however, they were one of the “Heavy” regiments pulled into the gory whirlpool of the 1864 Overland Campaign. The 9th never returned to its comfortable D.C. barracks, and spent the rest of its enlistment enduring rugged marches and bloody fights.

In the spring of 2020, Alexander MacLeod, a descendant of a veteran of the regiment, donated 22 letters written by Lewis Foster, along with approximately 40 other missives penned by 10 other members of the unit and scores of other documents related to the 9th NYHA’s service, to the care of Shenandoah University’s McCormick Civil War Institute. All of these letters appear in “A Good Cause”: Letters from the Ninth New York Heavy Artillery. The letters excerpted here from Foster and an unidentified member of the regiment, offer insight into the regiment’s tenure in the capital’s defenses, service with Army of the Potomac in the spring of 1864, and in the conflict’s final months.

Fort Gaines

May 28, 1863

Dear Mother,

I don’t see where the folks up north get the foundations for their rumors. I have not heard anything about this regiment being turned into infantry. Again the reason for the change of coats is that they want all the artillery to wear the same kind of coats. I don’t think we will leave here very soon… We are at work from 7 o’clock till ten. From 2 till 4 those that are not detailed on the fort have to drill on the big guns. I am detailed to work on the fort today… I am tired of working on roads and forts… I would like to go and garrison a Fort on the Sea Coast.

Give my love to all

Lewis

Fort Foote

January 25, 1864

Dear Aunt,

I have not been very well for about three weeks. It is three weeks ago today since I have done any duty. I am some better today… We expect our regiment will soon be filled up… It is so warm that the boys sit out by the side of the barracks in their shirt sleeves… We had some cold weather about a month ago. The river froze over so that the boys or some of them went across the river to Alexandria on the ice, but the ice is all out of the river now. [First Lieutenant Seth F.] Swift is getting to be pretty careless of his reputation, he drinks a considerable [amount]. He was on a spree one night with a lot of the officers and the next morning he was on guard and he was so drunk he could hardly stand up, he dropped his gun once, but the rest of the Officers was on and it all passed off. If the rest of the officers had not been on a spree with him and he come out to guard mounting drunk as he was then he would have been reduced to the ranks in no time. Cap[tain Harvey Follett] don’t drink much now, his wife is here and he carries himself pretty straight.

Your affectionate nephew.

Lewis

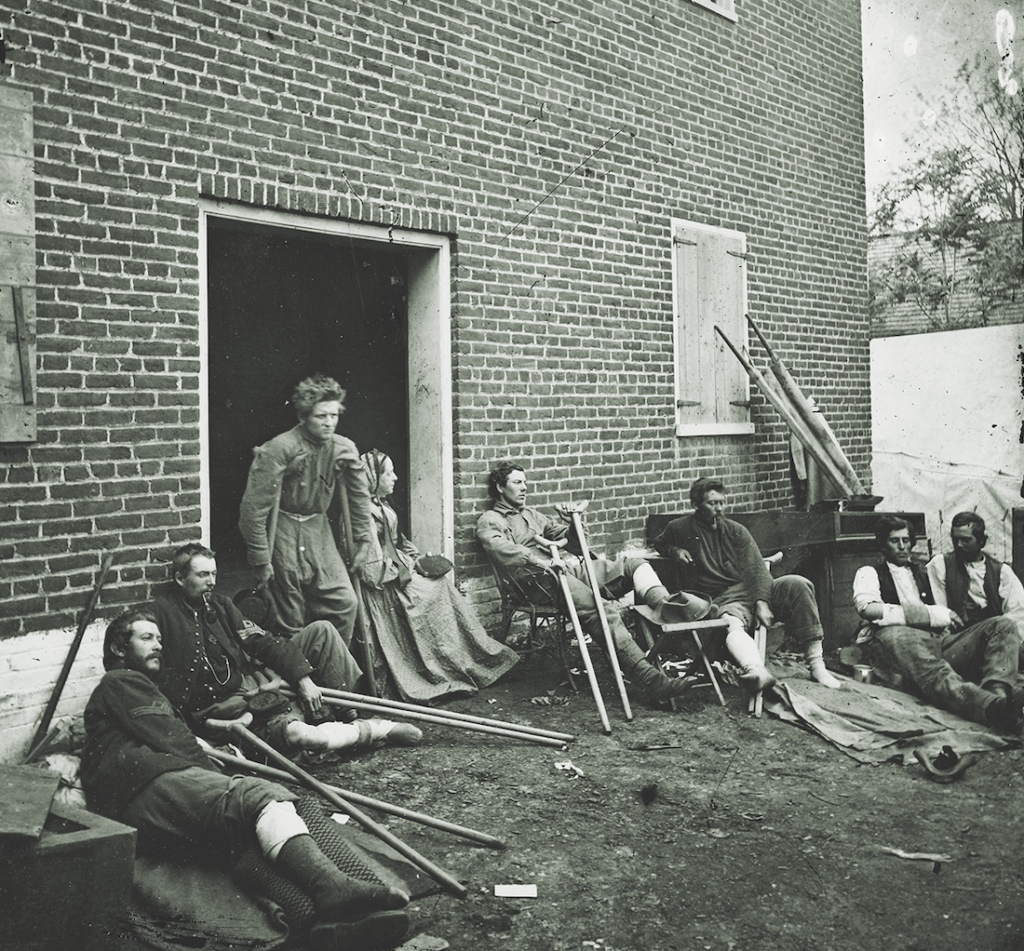

Although the work the regiment performed during its first 20 months of service—building roads, strengthening existing defenses, constructing new fortifications, and garrison work—proved important, some of the regiment’s members noted that they were “not particularly proud of its reputation” as construction laborers. They wanted to fight. That opportunity came in the late spring of 1864 when the regiment was ordered to join Maj. Gen. James Ricketts’ division of Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s 6th Corps. On May 18, 1864, the 1,900 men who comprised the 9th NYHA boarded three steamers—John Brooks, John W.D. Prouty, and State of Connecticut—and headed “to the front.” The scenes the regiment witnessed at Belle Plain Landing and in Fredericksburg, wounded from the battlefields of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, proved jarring.

When the 9th joined the 6th Corps near the end of the month the men seemed “particularly pleased” to be part of it. However, the corps’ veterans wondered how this regiment, now commanded by Secretary of State William Seward’s son, Colonel William Seward, Jr., would perform in combat. While some of the 6th’s veterans derisively referred to the 9th as the “White-gloved Soldiers,” those labels no longer seemed fitting after the regiment’s baptism of fire at the Battle of Cold Harbor on June 1, 1864—an engagement in which the 9th suffered 148 casualties.

Fort Ward, VA

May 17, 1864

Dear Mother,

Our Co[mpany] was sent to Fort Ward….We expect soon to go to the front. Our bed ticks have been turned in to the Quartermaster. We have turned in our shoulder scales and have to turn in our dress coats and draw blouses. A blouse is a loose kind of a sack coat, it is cool and comfortable. The barracks that we are in now are good comfortable ones. They are well ventilated with lots of doors and windows and on the roof is three little cupolas. The sides are made of slats so the barracks are well ventilated, our beds are easily described. We have got bunks and good soft boards to lay on with our knapsack for a pillow. We have orders to be ready to march at any time that we are called upon. We have got a lot of hard tack here ready so when we do march we can bid good bye to soft bread… There is lots of wounded soldiers coming into the city every day… According to reports Grant is whipping Lee all to pieces….Grant is bound to crush Lee before he can get to Richmond and I think he will.

My love to you mother,

Lewis

Fredericksburg

May 21, 1864

Dear Mother,

On the 18th our regiment embarked on board a transport and steamed down the river about 70 miles to Belle Plain Landing at the mouth of the Potomac Creek. It took three transports to carry our regiment… What sights of government property did we see there. There was train after train there of wounded soldiers and rebel prisoners….There is lots of guerrillas in this neighborhood. They quite often attack our trains. Every train has to be guarded from one station to another….There is lots of soldiers here and more coming every day. The rebel prisoners that are here are sulked and will not answer any questions. I don’t blame them for that….There is a train of ambulances at the dock that just came in from Grant’s army with wounded. Some are wounded in the arms, hands, some in the leg or feet, some in the head and face, some in the body…we may see some wild rebels before long.

Your loving son,

Lewis

Cold Harbor

June 8, 1864

Dear Aunt,

We have had one hard fight [Cold Harbor], probably you have heard….I went through the battle without a scratch except a slight mark on my nose. We had to fight in the woods. I stood behind a tree loading my gun when a ball struck the tree and glanced off a piece of bark hitting me on the nose starting the blood a little… Four companies of our regiment were supporting a battery….Our regiment was left back from the division to guard a wagon train but about one o’clock on the morning of the 1st of this month we was ordered to join our brigade. We marched about 10 miles and overtook our brigade then we marched about 7 miles and stopped and built a rifle pit and about three o’clock we was ordered to fall in line and attack the enemy. Our brigade formed in line of battle and charged on the enemy… We charged across an open field into the woods where the rebels were, we drove them through the woods…. Some of our boys got rebel haversacks with cornbread and bacon. I got some of their bacon….We have laid in reach of bullets every day this month….Some of the rebel prisoners say that if we drive them from this position Richmond is gone up. I hope it is so….Our men sent in a flag of truce last night for a cessation of hostilities to bury the dead. Our men and the Rebels met each other half way and exchanged papers. Our men are building rifle pits and batteries. They calculate to shell the rebels when they get everything ready.

Lewis

On July 5, 1864, Ricketts’ division, due to the threat Confederate General Jubal Early posed to the nation’s capital once his command of approximately 14,000 troops pushed beyond Harpers Ferry, received orders to “take transports for Baltimore.” After arriving in Baltimore on July 8, the regiment boarded train cars that carried them west to Frederick, Md. The following day, the 9th NYHA fought in what would be one of its costliest engagements—the Battle of Monocacy. The 9th suffered 207 casualties, Colonel Seward among them. In addition to receiving “a slight wound in the arm,” Seward broke his ankle after his horse “was shot” and fell on him.

Nine days after Monocacy, the regiment, although not engaged, “came under fire” along the banks of the Shenandoah River at the Battle of Cool Spring. Over the next three months, the 9th NYHA experienced incessant marching and intense combat in the Shenandoah Valley as part of Union Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s Army of the Valley.

Camp Near Kernstown, VA

November 26, 1864

We had a sort of Thanksgiving dinner yesterday, but it was a small fry. I tell you there was turkey and fowls of every [sort] sent by the folks at home, but they had to pass through so many officer’s hands before they got to us that there was not much left… It is reported in Camp today that the rebels are evacuating Petersburg, but I don’t believe it. It is only a rumor… You would laugh to see the huts we have got up here. They look almost half like beaver huts or something of that kind and [you] would smile to see the tools we have borrow[ed] from farmers here….We came across a wagon shop with lots of wagon spokes in it, all carved good….It was an old Rebel that owned the shop and I think he was a guerrilla as there was a lot of blue clothes found between the ceiling and the clapboards of the house….We took all the hay [he] had and a lot of potatoes and cabbages… Our men captured one Johnnie and the prisoners that our men captured today says that the Rebel soldiers are almost all tired of fighting and that there is lots of them that would desert and come into our lines but they cannot. They are kept well guarded. He also says that there is lots of them skulking around in the mountains that would come into our lines but they are afraid that the Yankees will treat them as they do guerrillas and that is to hang them. Some of the folks hide their things in the woods and bury them, but the boys manage to find the most of it. Today the boys found a lot of honey, butter, potatoes, cabbages, and other edibles hid in the woods.

Your affectionate son,

Lewis

During the first week of December, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered the 6th Corps to move from the Shenandoah Valley back to Petersburg. Shortly before noon on December 3, 1864, the 9th NYHA broke camp, marched to the train depot north of Winchester, and boarded cars that carried them to Harpers Ferry. Two days later the regiment reached Petersburg. Although the New Yorkers returned to a familiar place the regiment’s veterans reflected upon how different the unit looked compared to when it departed Petersburg the previous summer. The fighting from Monocacy to Cedar Creek had taken its toll. “Scarcely more than half as many men return to Petersburg as left it in the preceding July. The months had sadly ravaged our ranks,” one of the 9th’s veterans recalled.

Fort Wadsworth, VA

December 27, 1864

Dear Mother,

It is pretty rough times here now for some reason or another. We don’t get more than half enough rations now… One of the boys that tents with me… bought bread and flour and so we have got along better than some of the boys… We have more duty to do than we did in the summer. We have to do picket duty, guard duty, drill, and 25 men have to stay to the fort half of the night and keep awake and we have to all get up at five in the morning and stay to the fort until daylight then we have to carry our wood nearly a mile.

Since we got the news of the capture of Savannah there has [been] 180 rebs come into our lines. They said that a whole brigade started but some of their own batteries were turned on them. Some … say that there is thousands of them that will come to us as soon as they get paid again so their families can have the money to keep them from starving.

Your loving son,

Lewis

Fort Wadsworth

February 4, 1865

Dear Mother,

The pickets keep firing all the time. Once in a few minutes our reserve pickets fire a volley that stops the rebs for a while but they soon commenced popping again. There is all kinds of rumors in camp about peace. Some says they heard that peace was soon going to be declared and some says that [Francis] Blair’s mission to Richmond was an entire failure. Then rumor says the peace commissioners have gone to Washington from Richmond to see what terms can be agreed upon, but I don’t credit much of it, but I hope it is true… I wish the war would close and that we could go home….I have seen men enough killed to satisfy my war fever entirely.

From your loving soldier boy,

Lewis

Fort Fisher [Petersburg, Va.]

February 18, 1865

Dear Mother,

We have left Fort Wadsworth and are quartered at Fort Fisher about three miles from our other camp….The Rebel lines are but a short distance from our own and we can see them very plainly when they are at work on their forts and breastworks. There is no firing on the picket line except [when] the Johnnies try to desert….The picket lines are close to them and their men desert very fast. Some nights if it is pretty dark some few to twenty will come in one night. Sometimes a squad of the Johnnie’s pickets will come half way and some of our boys go out to meet them and talk with each other. We have got some strong works here, and if the Johnnies pitch into us here we will give them a warm reception….I can hear the pickets yelling at each other.

From your loving son,

Lewis

Following the Army of Northern Virginia’s surrender on April 9, 1865, the 9th NYHA protected the Richmond and Danville Railroad. The 9th performed this duty until May 22, when it was ordered to proceed north to Washington, D.C. On June 8 the regiment, along with the entire 6th Corps, participated in the Grand Review of the corps. While the review, as one of the regiment’s veterans recalled, presented an opportunity for “all those who had fought to save the Capital might, in triumph, march through its streets,” as the following excerpted letter, penned by an unidentified member of the regiment, notes it was a miserable experience.

Camp 9th NYHA

Near Washington, D.C.

June 9, 1865

Dear Parents,

We had that great Review yesterday. I thought I would write a few lines to let you know that I was one of the number to live through it, but I had a pretty rough time of it. The day was scorching hot there was not the least bit of air in the city. There was a great many men sun stroke & some died, some dropped dead in the ranks. Officers fell from their horses….It must [be] a great pleasure for them head officers…there is no use of these reviews….I shall not go on another review, if we have to go on another I shall fall out the first thing… All that lacks of our coming home is making out our discharges & our transportation….I don’t think I would give much for a soldier’s labor when we get home for they are like a lot of broken down horses. It will take food, clothing, rest, & washed about 3 times a week in warm water with some good bay rum in it to get his hide cleaned, a glorious old physic & the thorough cleansing of the blood & stomach to make anything of the worst of us.

Foster mustered out of the regiment on July 18, 1865, he returned to New York, but did not remain long in the Empire State. In 1867 Foster and his new bride, Albina (the couple married on September 15, 1867), headed west to Nebraska. According to Foster’s pension file the Foster family, which eventually included three children, lived and labored in Beaver Creek and Lincoln as a farmer for 25 years. For reasons unclear, the Fosters moved to Powhatan County, Va., by 1896. On September 28, 1912, battling various ailments including chronic rheumatism, arteriosclerosis, and “mental insufficiency,” Foster was admitted to the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Hampton, Va. He died at the home on November 2, 1912, and was buried in the Hampton National Cemetery.