Driven Mad By His Wife’s Passing, This Union Soldier Suffered an Ignoble Death

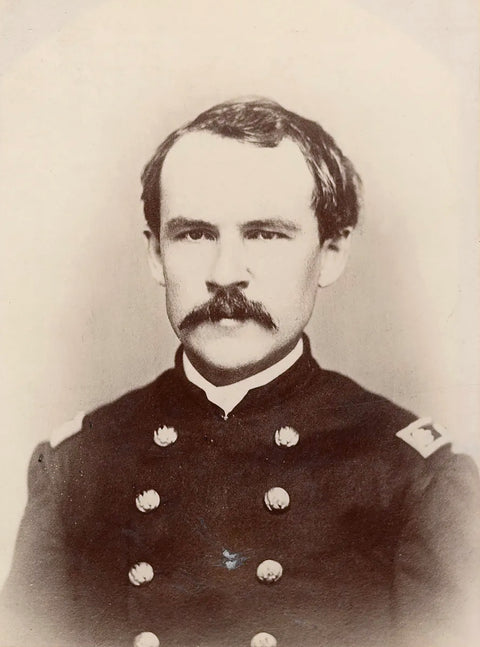

The Rev. George W. Pye waited in Dr. Abram H. Knapp’s office for a hospital attendant to retrieve his friend, Colonel John Wesley Horner. Pye was dismayed by Horner’s appearance. Before him stood a pale man with a restless stare, a once-proud veteran who anxiously rubbed his hands together and pulled at his facial hair. When Pye tried to talk to Horner, the colonel motioned that he was too feeble to talk and only answered in what the minister described as “indistinct monosyllables.”

“The colonel is a shadow of himself,” Pye recalled after the distressing visit. “[S]uch a look lingers with me yet.” He never visited his friend at the Kansas State Insane Asylum again, and when Horner died three months later, he was buried unceremoniously alongside the sanctuary’s other deceased patients.

A teacher before the Civil War, Horner was appointed a first lieutenant in the 90-day 1st Michigan Infantry in May 1861 and fought at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21. After the Union defeat, he was mustered out, but was then appointed a captain in the 18th Michigan Infantry in August 1862. By March 1865, Horner was the regiment’s colonel and had served in various administrative posts, such as the provost marshal in Nashville, Tenn., and in the District of Northern Alabama. He ended the war as the commander of the U.S. post at Huntsville, Ala.

Relocating to Kansas, Horner resumed his teaching and writing career. He became president of Baker University in Baldwin City, Kan., and a professor of mental and moral philosophy at Kansas State University in Manhattan. Horner also served as the superintendent of Chetopa’s schools and started the Chetopa Advance newspaper. The Manhattan Beacon called him “one of the foremost educators in this portion of the State, an eloquent speaker and a brilliant essayist.”

Shrouded Veterans recently placed a Civil War veteran headstone inscribed with

Horner’s name and military service at the hospital’s cemetery.

In November 1873, however, Horner’s wife, Abigail, was stricken by an unknown brain disease, dying only two days after she had been diagnosed. A few weeks later, Horner suffered a mental breakdown and even attempted suicide several times. On December 29, he was admitted to the Kansas State Insane Asylum in Osawatomie. Abigail’s sister, Caroline Stocum, stepped in to care for his two young daughters, Catherine and Alice.

Horner finally passed on August 16, 1874, just 40. “His insanity and subsequent death are not only a great and irreparable loss to our country” reported the Chepota Advance. “It is a calamity to our State.”

Although Horner’s friends in Chetopa sent a telegraph to the Kansas State Insane Asylum requesting his remains be shipped home on the first available train—and also scheduling a funeral for the day the body would arrive—the missive apparently never reached the asylum and he was interred on the hospital’s grounds.

At the time, patients who died were buried with only their patient number carved on a simple marker, no names. Shrouded Veterans recently placed a Civil War veteran headstone inscribed with Horner’s name and military service at the hospital’s cemetery.