A Mother’s Grief

Russell Forrest Keck, nicknamed “Rusty,” was a 20-year-old serving in the U.S. Marines when he was killed in Vietnam on May 18, 1967. A Machine Gun Squad Leader of Company A, Battalion Landing Team 1/3, Ninth Marine Amphibious Brigade, Rusty was taking part in Operation Beau Charger in Quang Tin Province when he sacrificed his life to save a comrade.

Posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for his heroism, Rusty was credited with “courageous actions, bold initiative, intrepid fighting spirit and sincere concern for others.” He “rushed to the aid of his men under vicious enemy fire, finding one lone survivor,” according to his award citation, and despite being wounded by a grenade, managed to take down an approaching enemy. Knowing that “only one man could possibly make it back across the deadly fire-swept terrain,” Rusty told his comrade to run for it while he provided covering fire. Tragically, Rusty was killed.

His loss was deeply felt by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Keck. After his burial, his mother brought her grief straight to the person who she believed was responsible for their terrible loss — U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson himself, who she had written to earlier to express her worries about her son’s life…in vain.

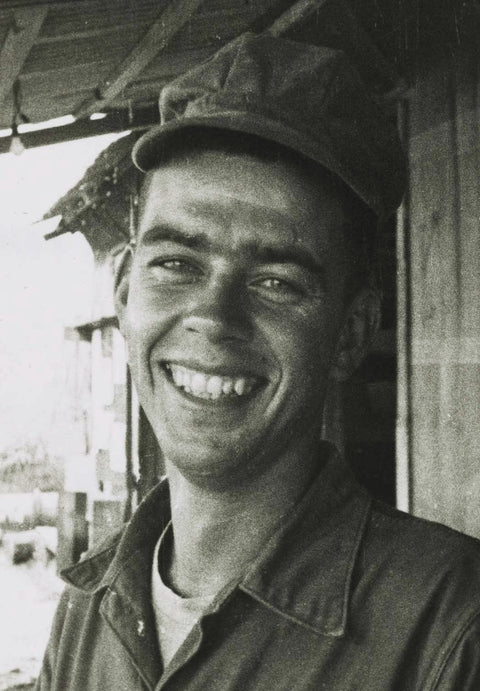

Along with her letter, Mrs. Keck also sent Johnson a photo of her smiling son — drawing attention to the face that neither she nor her husband would ever see again, nor were able to look at even for one last time due to the horrific injuries their son had received in battle.

Here is what she wrote to the president:

Dear Mr. Johnson,

Not long ago, I wrote you objecting to our son’s short military training period, prior to being flown to Vietnam, and the fact that he was fighting when many South Vietnamese were not. I based this latter view on my husband’s report of what he had seen during his visit to Vietnam last fall.

Well, Mr. Johnson, yesterday we buried our son. He was hurt so badly we were not able to see him. But we do have a photograph that my husband took while he was with him in Da Nang, and I’m sending you a copy.

While it would be easier for us to believe that his death was God’s will, the fact is that you are responsible for taking his life.

She went on to say that Johnson could have prevented her son’s death and that it was within the president’s power to prevent further “deaths and sufferings” in other families.

Johnson had not answered Mrs. Keck’s first letter, written while Rusty was still alive, but he responded to this letter following the young man’s death — although White House records show that the commander-in-chief found it difficult.

The numerous scribbles and cross-out marks on one of Johnson’s drafts demonstrate that he had difficulty expressing himself clearly on two matters — responding to the parents’ grief, and addressing the issue of his own responsibility.

Looking at Johnson’s confused scribbling in response to this heartbreaking loss, and in view of of Rusty’s last act of heroism, raises some important questions about the nature of duty and leadership. Could President Johnson have done better in this situation? If so, how? Was his higher duty to America as a nation, as he suggests in his draft, or did he fail to consider that families such as the Kecks — and individual soldiers making heroic sacrifices like Rusty — were part of the nation he was elected to serve? How do you think Johnson comes across in his various attempts to answer the family?

Reflecting on this, we may stop and think for a moment about the responsibilities we entrust to those we elect to political office, and to what extent political leaders are responsible for lives affected by their decisions.