Why Did Lincoln’s Right-Hand Men Call Him the ‘Tycoon’?

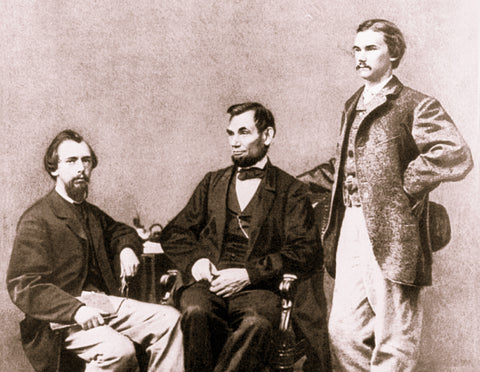

John G. Nicolay, John Hay, and William O. Stoddard served as secretaries to Abraham Lincoln. Nicolay and Hay worked in close proximity to their chief throughout the war, while Stoddard spent significant time in the White House between July 1861 and July 1864. Loyal to “The Tycoon,” as they called the president, the three young men logged endless hours and experienced frustration and exhilaration in generous measure. They also created valuable testimony that Southern Illinois University Press published in a quartet of essential volumes: Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay (1997); Burlingame, ed., At Lincoln’s Side: John Hay’s Civil War Correspondence and Selected Writings (2000); Burlingame, ed., With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865 (2000); and Harold Holzer, ed., Lincoln’s White House Secretary: The Adventurous Life of William O. Stoddard (2007).

Hay’s observations shed light on innumerable events and personalities. On November 11, 1864, the just re-elected Lincoln spoke to his Cabinet about the famous “Blind Memorandum.” He took the document, written on August 23, 1864, from his desk and said, “Gentlemen do you remember last summer I asked you all to sign your names to the back of a paper of which I did not show you the inside? This is it.”

The president “had pasted it up in so singular style that it required some cutting to get it open” before he could recite the brief text: “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so cooperate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterwards.”

Lincoln next explained that in late August he had believed George B. McClellan would receive the Democratic nomination and meant to urge “Little Mac” to “raise as many troops as you possibly can for this final trial, and I will devote all my energies to assisting and finishing the war.” Secretary of State William H. Seward remarked that McClellan would have said, “‘Yes—yes’ & so on forever and would have done nothing at all.’ ‘At least’ added Lincoln ‘I should have done my duty and have stood clear before my own conscience.’”

GET HISTORY'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit

Hay’s diary underscores Lincoln’s disappointment in the wake of Gettysburg. On July 11, though “rather impatient with Gen Meade’s slow movements,” the president believed his general “would yet show sufficient activity to inflict the Coup de grace upon the flying rebels.” Three days later “the Prest. seemed depressed by Meade’s dispatches of last night. They were so cautiously & almost timidly worded—talking about reconnoitering to find the enemy’s weak place and other such. He said he feared he would do nothing.”

On July 15, Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s eldest son, “says the ~~Tycoon~~ President [Hay made the substitution] is grieved silently but deeply about the escape of Lee. He said ‘If I had gone up there I could have whipped them myself.’ I know he had that idea.”

A year earlier, Nicolay described reaction to George B. McClellan’s retreat after the Seven Days’ Battles. President Lincoln recently made a “flying visit” to the Army of the Potomac and seemed to have “returned in better spirits.” For the public, in contrast, it “has been a very blue week here among all classes of society….I don’t think I have ever heard more croaking since the war began than during the past ten days.” Many leaders exhibited “little real faith and courage under difficulties,” commented Nicolay, while the “average public mind is becoming alarmingly sensational. A single reverse or piece of accidental ill-luck is enough to throw them all into horrors of despair.” Although Nicolay played down the significance of McClellan’s failure at Richmond, his letter suggests the degree to which the Seven Days’ countered recent Union success in other military theaters.

On August 25, 1864, Nicolay vented to Hay about the volatile political situation that had prompted Lincoln’s solicitation, two days earlier, of signatures on his blind memorandum. “Hell is to play,” he began, “The N.Y. politicians have got a stampede on that is about to swamp everything.” Moreover, “Weak-kneed d---d fools like Chas. Sumner are in a movement for a new candidate—to supplant the Tycoon.”

William

O. Stoddard wrote memoirs that remain an important source on the Lincoln White

House, even if exaggerated at times.

With everything in “darkness and doubt and discouragement,” Nicolay thought the nation had reached “a turning point in our crisis.” He lauded Lincoln’s “patience and pluck” and hoped other Republicans would emulate his example. “If our friends will only rub their eyes and shake themselves,” he concluded, “and become convinced that they themselves are not dead we shall win the fight overwhelmingly.”

William O. Stoddard’s recollections of Lincoln, notes editor Holzer, inspired dismissive comments from both Nicolay and Hay. Historians also have questioned some of Stoddard’s claims, as when he insisted the president asked him to manage the substitution of Andrew Johnson for Hannibal Hamlin as the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1864. Yet his autobiography contains ample material of interest. Charged with sorting the mass of unsolicited daily mail addressed to Lincoln, Stoddard had his pulse on the concerns and attitudes of the loyal citizenry and created excellent snapshots of key moments in the war.

One such moment conveys anticipation of public anger over news of Joseph Hooker’s ignominious defeat at Chancellorsville. Nicolay remembered that “[A] terrible, great, black cloud…came rolling across the Potomac and into the White House from the lost battlefield of Chancellorsville.”

John Hay told him that “Stanton says this is the darkest day of the war. It seems as if the bottom has dropped out.” Stoddard knew on that “awful day,” when it “almost seemed as if the White House itself had been transferred to the battlefield,” what the mail would soon bring. “[T]he wails and the mourning…would quickly come down from the North,” he foresaw, “and, mingled with these, would be the sounds of despair and the unsuppressed curses of the unreasoning people who would surely hold Mr. Lincoln and his administration responsible for this one more lost battle and its dead.”

Best read together, Lincoln’s secretaries afford readers an insider’s glimpse into an administration caught in the crucible of a great war. They also remind us of our debt to scholarly editors and university presses.