When Germany Attacked Norway It Aimed to Capture the Country’s Gold. The Norwegians Stayed One Step Ahead.

At 4:16 a.m. on the frigid morning of April 9, 1940, the German heavy cruiser Blücher steamed within view of the Norwegian fortress of Oscarsborg. The Blücher and its accompanying ships formed Gruppe V of Operation Weserübung , Germany’s unprovoked invasion of Norway. Gruppe V was one of six naval task forces making synchronized dawn attacks on all of Norway’s key coastal assets, stretching from Kristiansand in the south to Narvik, more than 1,000 miles to the north . Situated on a small island in the middle of Oslofjord, Oscarsborg provided the last line of defense for Oslo, Norway’s vulnerable capital and its largest city.

Of all Weserübung’s targets, Oslo was the biggest prize. It was home to the royal family, the Storting (Norway’s Parliament), all government offices, and the headquarters of the Bank of Norway, guardian of the nation’s gold reserves. In their earlier incursions into Austria and Czechoslovakia, invading Germans had seized almost 140 tons of gold to help finance their military juggernaut. Norway’s reserves now appeared within their grasp as well.

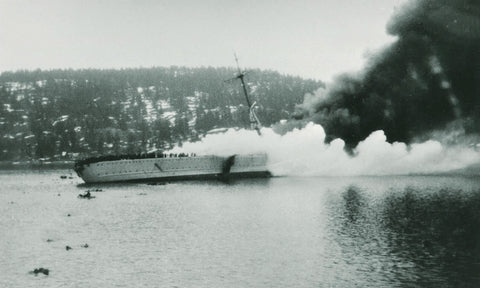

In the murky pre-dawn light, Colonel Birger Eriksen, Oscarsborg’s commander, had a split-second decision to make. Was the flotilla friend or foe? Attacking it would either make him a hero or result in a court-martial. Nevertheless, he didn’t hesitate. Eriksen’s men shot first and two 560-pound shells slammed into the Blücher with devastating effect. Two torpedoes from a nearby shore battery did the rest, and the ship capsized and sank, killing a large portion of the crew as well as the invasion force. The remaining ships in Gruppe V prudently retreated down the fjord to regroup. Norway was now at war with Germany.

By sinking the Blücher, Eriksen bought Norway’s leaders precious hours to organize an evacuation of King Haakon VII and members of his government. By 7:30 a.m. they had all departed Oslo on a special train, heading north to Hamar, 80 miles away.

A gold coin

bears the likeness of Norway’s King Haakon VII. The nearly 54 tons of gold

that Norway denied the Germans included coins like this.

But what of the gold housed in the Bank of Norway?

Norway’s government had fervently hoped that Hitler would respect its neutrality and as a result had been taken completely by surprise by the events of April 9. Norway’s central bankers, however, had taken no chances. In the years, months, and weeks leading up to the invasion, Nicolai Rygg, governor of the Bank of Norway, made three crucial decisions. First, starting as early as 1936, Rygg had ordered the construction of three special bombproof vaults: in Oslo, in Stavanger on the west coast, and in Lillehammer to the north. Secondly, following the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939, Rygg moved the bulk of Norway’s gold reserves (134 tons, or more than 70% of its total holdings) to safety in the United States and Canada, leaving only the minimum amount required by law in Oslo. Thirdly, Rygg had all remaining bullion, still weighing in at 53.8 tons and worth about $3 billion in today’s valuation, carefully packed into 1,542 sturdy wooden crates and barrels for immediate transport. Without this latter effort, it would been impossible to pack and move such a large shipment in the few hours Eriksen had purchased at Oscarsborg.

One matter Rygg had not yet addressed, however, was an emergency evacuation plan for transporting such bulk at a moment’s notice. In the early morning of April 9 bank officials scrambled to round up 25 trucks. The drivers were not told what they were transporting and were warned they could be bombed and strafed along the way. Nevertheless, with no time to ask questions, weigh risks, or even alert their families, they stepped up. It was the first of what would be many such selfless acts in the attempt to save Norway’s gold.

Loading almost 54 tons of gold (including the crates, the total payload came to 58.4 tons) was backbreaking work, equivalent to moving almost 1,300 90-pound bags of cement. Once loaded, each truck immediately set off for the bombproof vault in Lillehammer—115 miles to the north. The last truck departed Oslo early on the afternoon of April 9, just minutes before the first German column finally marched into town and accepted the local garrison’s surrender.

Norway had won the opening round.

Lillehammer’s vault could shelter the gold only so long as the city held. Unfortunately, Norway’s armed forces—a hasty patchwork of partially mobilized units, volunteers, and even rifle club members—were no match for a heavily armed foe with mastery of the air. Within days it became clear that Norway could not defend Lillehammer indefinitely. It was also apparent that safeguarding and transporting gold in wartime required skills not typically found in a central banker. Consequently, on April 17, Oscar Torp, the minister of finance, authorized Fredrik Haslund to take charge of the effort. Haslund, age 41, seemed an unlikely choice. Trained as an engineer, he was at the time secretary of Norway’s Labor Party. Torp, as the party’s head, must have noticed something special about Haslund’s organizational skills and resourcefulness. As events would prove, Haslund was an inspired choice.

On the night of April 18-19, all 58.4 tons in the Lillehammer vault were loaded back onto trucks for the short drive to the local train station, where it was transferred to awaiting train cars. Haslund’s destination was Åndals- nes, a port town of 2,000 lying 150 miles northwest of Lillehammer at the head of the Romsdalsfjord. It appeared to be a sensible move. The British, rushing to Norway’s aid, had landed at two sites in central Norway: Åndalsnes, south of the strategic city of Trondheim, and Namsos, a port north of Trondheim. Åndalsnes thus seemed to offer the strength of British arms to protect the gold, and, should the worst occur, the ability to evacuate the gold by sea.

The situation, however, also had drawbacks, since the British presence acted as a magnet for Germany’s Luftwaffe. Shortly after the gold train arrived in Åndalsnes at 4:30 a.m. on April 20 the Luftwaffe arrived to pound the town with relentless air attacks. Instead of being a refuge, Åndalsnes became a target. The town—almost entirely wood-built—became an inferno. British ships could safely load and unload only between nightfall at 10:00 p.m. and sunrise at 6:00 a.m., when German airplanes once again filled the skies. In the face of all this, the gold train hastily retreated a few miles southeast to a secluded rail siding in a steep valley. That same day, Norwegian officials notified their stunned British counterparts that all of Norway’s remaining gold lay hidden on a nearby train and requested help evacuating it to England.

By now it was apparent that safeguarding the gold in the face of relentless German advances was almost impossible, and that the British—unprepared, disorganized, and poorly equipped—were losing the battle of Norway. Lillehammer fell to the Wehrmacht on April 22. As in Oslo, the Germans rushed to the offices of the central bank and once again found an empty vault. Norway had won round two.

German

soldiers advance deeper into Norway. The invasion took the Norwegians and the

British by surprise.

With little left in Åndalsnes to destroy, German air attacks slowed, and Haslund took advantage of the lull to deliver 200 cases of gold, weighing almost nine tons, portside. HMS Galatea , a British light cruiser, had just arrived with British troops and equipment. By early morning on April 24 all soldiers and supplies had been disgorged and the gold onloaded. The Galatea sailed off. Two days later the ship and its special cargo arrived safely in Rosyth, Scotland.

As Galatea retreated down Romsdalsfjord, Haslund turned his attention to the slightly more than 49 tons still in his care. True, the Germans didn’t know exactly where it had gone, but they certainly understood that the gold must be somewhere along the rail line between Lillehammer and Trondheim. In any event, Åndalsnes had become completely untenable. The village was in shambles, and the British were growing increasingly nervous about risking their capital ships inside the narrow fjords. Moreover, the Germans were close to breaking through the new defensive line the British and Norwegians had hastily thrown up after Lillehammer fell.

The port of Molde, 30 miles by land northwest of Åndalsnes on the Romsdalsfjord, offered a sheltered, deep-water harbor that had escaped the kind of attention the Luftwaffe had lavished on Åndals-nes. Equally attractive to the British, it was closer to the open sea. Unfortunately, there was no rail connection with Åndalsnes, and only one rather primitive road, which included a ferry crossing, linked the two towns. But Haslund didn’t have many other options; the Germans were approaching from the south and time was running out.

Consequently, he had the remaining 1,342 cases of gold laboriously detrained and reloaded onto trucks for the perilous trek to Molde. The narrow, unpaved road was pocked by bomb craters and potholes; conditions were exacerbated as the spring thaw turned such roads to mush. As overloaded trucks broke down, their contents had to be redistributed to others in the convoy. Farmers along the way were roused in the middle of the night to enlist their draft horses to rescue trucks that had slipped into ditches. The ferry along the route could handle only two trucks at a time; it took six hours for the entire convoy to make it safely across the narrow fjord. If that were not enough, the convoy was repeatedly strafed, but miraculously emerged unscathed.

In the early morning hours of April 26, the convoy finally reached Molde, a town of 3,200 inhabitants. The gold was unloaded and stored in the basement of a factory that was close to the town pier and had a basement of reinforced concrete.

When German forces entered Åndalsnes on May 2, only hours after the last British soldier had been evacuated, they found the town in ruins. But once again they found no gold. Norway had won the third round.

If Haslund hoped that Molde would offer a respite from the chaos of Åndalsnes, those hopes were quickly dashed. The Luftwaffe started its assault shortly after the last case of gold had been unloaded into the factory basement. This could not have been due to the gold, because its location remained a mystery to the Germans. A more likely explanation was the arrival, on April 23, of King Haakon and his government ministers, making Molde the de facto capital of Norway. The king’s location was supposed to be a closely guarded secret but, as one historian observed, “However they were receiving the information on the King, wherever he appeared, an uncannily short time later the bombers would arrive overhead.” Whatever the reason, Molde, like Åndalsnes, suffered mightily as incendiaries rained down from above.

Finally, on April 29, Haslund received instructions from the British to deliver the gold to Molde’s main pier at 10:00 p.m., when the light cruiserHMS Glasgow was expected. Glasgow’s primary, top-secret mission was to evacuate the king, his son (the crown prince), and other government officials to England or any other “place of safety” they chose. Haakon, still unwilling to abandon his country, chose to go to Tromsø, Norway’s northernmost city, located almost 850 miles north of Molde and still safely under Allied control.

The Glasgow reached Molde at 11:00 p.m. Its captain was determined to depart no later than 1:00 a.m. to ensure his ship was clear of the fjord and at sea before dawn. King Haakon, his son, and various government ministers boarded within minutes of the ship’s arrival, and the gold, delivered by small boats as well as trucks, soon followed.

At 1:00 a.m. a German Heinkel He-111 bomber passed overhead “so low that it seemed certain to hit our masts,” in the words of one sailor. The Glasgow got underway so quickly that one overlooked mooring hawser remained tied, and the ship dragged part of the quay into the sea. In what has been described as “seamanship of the highest order,” the cruiser, almost 600 feet long and displacing 11,000 tons, ran at full speed in reverse for over an hour down the narrow, twisting, and darkened fjord before turning around and sailing away.

In the space of two hours, under the most trying conditions, Haslund had gotten 29.5 tons of gold safely stowed aboard the Glasgow, leaving only 20 tons behind. After depositing the king and his ministers in Tromsø on May 1, Glasgow and its gold proceeded to Great Britain, arriving on May 4.

With all the confusion at the quay, some government officials and soldiers had not escaped with the king aboard the Glasgow, and they found refuge on a nearby steamer, the Driva. Haslund, with 20 tons of gold still on his hands, sent his remaining trucks racing through burning Molde to the undamaged pier where the Driva was taking on passengers. The gold transfer continued until an aerial bomb set the pier aflame and exploded so close to the Driva that it lifted the 330-ton steamer out of the water, miraculously without damaging it. This was a sign for Driva’s skipper to leave—gold or no gold. By then only about half the remaining reserves—10 tons—had been loaded.

It was now 2:00 a.m. Before the Driva departed, Haslund arranged with its skipper to rendezvous the next day in Gjemnes, a fishing village about 30 miles north of Molde, to take on the remaining 10 tons still on his trucks.

Steamers like the Driva were too slow to cross the North Sea to England unescorted, and too large to simply blend in with the small fishing boats that were ubiquitous along Norway’s coast. Before Driva had even reached Gjemnes, a Junkers Ju-88 bomber attacked. Rather than risk his valuable cargo, Driva ’s skipper ran the ship aground. Eventually the bomber moved on without scoring any hits, but the Driva was stuck fast by the bow. The crew started to manually transfer all the gold, then amidships, to the stern. The work was as toilsome as ever but, helped by a rising tide and a tow from a fellow steamer, the shipwriggled free and proceeded to its scheduled rendezvous in Gjemnes. Haslund, whose truck caravan had reached Gjemnes ahead of the ship, knew he needed to adopt yet another plan of escape—the Driva was simply too conspicuous to risk on a long voyage.

Haslund’s thoughts turned to “puffers,” stubby and broad-beamed fishing boats that got their nickname from the characteristic puff of smoke—and accompanying sound—from their single-stroke engines. As one historian noted, “The German pilots never seemed to realise the full value of the puffers to the Norwegians and the Allies.… Too small to be bombed under most circumstances, some puffers were machine-gunned if suspicion had been aroused. Unless the crew was hit directly, however, this had limited effect on the sturdy ships.”

Haslund requisitioned four puffers in Gjemnes to take on the remaining gold from the Driva and the truck caravan. He set aside a fifth puffer for the use of escaping officials and soldiers. By 2:00 a.m. on May 1, the flotilla got underway, ostensibly headed as far north as Namsos, where the British were still believed to be engaged.

On the way, Haslund’s puffer group learned that the British had already evacuated Namsos. The prospect of now transporting 20 tons of gold many hundreds of miles north, in defenseless boats, through German-patrolled skies and German-patrolled seas, seemed hopeless. In any case, the puffers’ skippers had not agreed to go farther than Namsos. They had risked their boats, their livelihoods, and their very lives for their country, but there were limits. Once again Haslund had to adopt a new expedient. He concluded that any flotilla larger than two boats—even puffers—might attract undue attention. So, at the tiny island of Inntian, lying at the mouth of the Trondheimsfjord, he had the gold reloaded—yet again—this time onto two larger, newly-requisitioned fishing boats, each carrying approximately 10 tons.

Thus began the final, and longest, leg of Haslund’s odyssey, and in many ways the most perilous, requiring all his improvisational skills. He was no longer in touch with his superiors. He lacked a clear picture of where the Germans were. The British had abandoned central Norway, leaving the Germans free to roam at will. In the chaotic, panicked atmosphere then prevailing in Norway, paranoia regarding any strangers ran high. Haslund’s mysterious party, on the other hand, couldn’t say where they were going, where they had come from, or what they were carrying. All this fed suspicions that they were spies, or worse; suspicions that hindered Haslund’s efforts to obtain needed information, supplies, and food along the way. For his part, Haslund didn’t know whom he could trust, given the suspected presence of “Quislings,” Norwegian traitors sympathetic to the Nazis. One false move could easily betray the entire mission.

The

last of the gold was finally loaded aboard the HMS Enterprise on May 24 and

transported to safety in England.

In addition to dangers lurking on land, enemy airplanes circled above and enemy ships roamed at sea. With each passing day, and each passing mile northward, the hours of daylight increased, and the crucial protection provided by darkness lessened. In fact, Tromsø, Haslund’s ultimate destination, has no true night after March 27 and before September 17 each year.

On May 9, 30 frenetic days since Colonel Eriksen’s bold actions bought Norway a few precious hours, Haslund’s two-boat flotilla sailed at last into Tromsø harbor. The gold’s 1,000-plus-mile odyssey, through almost the entire length of Norway, was over. The final 20 tons still needed to be moved—one last time—into the hold of the British light cruiserHMS Enterprise. It marked at least the seventeenth time some or all of Norway’s 58-ton gold reserves had been physically moved. On May 24 Haslund boarded the Enterprise and departed Tromsø along with his gold, reaching the English port of Plymouth five days later. All the gold was now safe.

Norway had won the final round.

Despite being totally unprepared for the Nazis’ sudden onslaught, the Norwegians had somehow accomplished something neither Austria nor Czechoslovakia had. Nor would many of the countries subsequently invaded by Germany succeed in safeguarding their gold reserves, a list that included the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Greece, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and Italy. Before Germany was finally defeated, it would seize a total of almost 600 tons of gold from nearly a dozen countries. But it did not get any from Norway.

Equally impressive, despite the multiple loadings and unloadings, always under chaotic wartime conditions, a mere 297 coins, amounting to a few pounds, were lost during the gold’s laborious trek to safety.

This remarkable feat represented Nicolai Rygg’s foresight, Birger Eriksen’s intrepidity, and Fredrik Haslund’s resourcefulness. But it also represented the incredible labor and unflagging courage of untold anonymous Norwegians—soldiers, truck drivers, train personnel, puffer crews, farmers, and townspeople—who helped keep the gold always one step ahead of the Germans.