What You Don’t Know About Ben Butler: An Interview with His Biographer

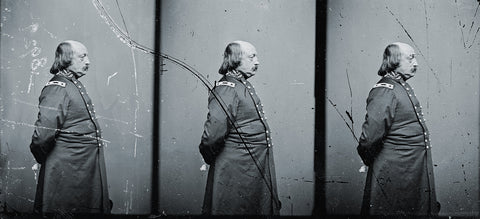

Elizabeth Leonard's interest in General Benjamin Butler was piqued when she was tasked to write a description for a large portrait of the alumnus of Waterville College (now Colby College) when it was reinstalled in the college’s alumni center. What she found paints an entirely new portrait of the politician and general in Benjamin Franklin Butler: A Noisy, Fearless Life. In fact, the book’s cover image is an unfamiliar photograph of Butler. “That’s exactly what I want you to feel,” Leonard says: “It’s him but it’s not him. You think you know him, and you do, but you don’t.”

Elizabeth Leonard (Photo by Thom Blackstone)

CWT: Tell us a bit about his early life.

EL: He was born in New Hampshire, born into a situation of relative poverty, and very soon his father was gone. His mother wanted him to be able to do well and sent him off to school and she went down to Lowell, Mass., to become a boardinghouse-keeper in those early days of the Lowell mills. He soon joined her there. And that was his home for most of his life.

CWT: How did he become a general?

EL: He had wanted very much to go to West Point. It was not possible for him to do so. His mother sent him up to Waterville College in Maine, where his portrait hangs in our alumni center here. When he was back in Massachusetts pursuing his career as lawyer, he joined the Massachusetts volunteer militia. That would serve him well when the war came and he was able to position himself as someone who had previous military and leadership experience.

CWT: He was involved in the war from the start.

EL: His ego was never weak. A combination of true patriotism and a desire, always, for glory and military opportunity. All those things combined to make him one of the first—he and his regiments—to be involved in the defense of Washington in those early days. He’s everywhere: he’s in Baltimore when the first troops are being shot at; he’s at Fort Monroe when the enslaved people are coming for protection.

CWT: You describe his talents as an administrator, and that he helped found the veterans’ homes.

EL: Some people have a natural ability for organization. He seemed to have it in spades. Even people who didn’t like him couldn’t say he was a bad administrator. It seemed to allow him to survive—people realized he had too much talent, but sometimes too much is threatening. He did so much in New Orleans that people were begging him to come back and keep New Orleans clean.

CWT: People know him as the guy who stole the spoons. Did you know about his commitment to Black civil rights and support for the poor?

EL: Absolutely not. It’s really interesting how much I didn’t know about him and how powerfully the repressive influences have extracted all of his contribution to Black rights he strove so hard to make. But I had two clues: Harold Raymond, my predecessor at Colby, wrote in 1964 that Butler deserves a reappraisal, and I knew this wonderful historian wouldn’t say that if it wasn’t so. Then Gary Gallagher suggested I look into his story more deeply. The comparison between the Beast Butler/Spoons Butler mockery, including the images and illustrations of him that had been so common, and what I saw from this other group of people was stunning. Frederick Douglass sent a massive floral display to his funeral and his son was a pall bearer at his funeral.

CWT: Spell out that commitment.

EL: The first thing he did was not to return the three enslaved men who came to him at Fort Monroe. The news spread like wildfire, and hundreds soon came. For him, it was a big step on his journey. There was his experience in New Orleans: He turned the Louisiana Native Guard into Union soldiers and had this ongoing contact with enslaved people and their desire for freedom and the sacrifices they were willing to make. Then there’s his work with the Army of the James and its Black regiments. After the war he never looked back. He rode past the dead bodies of his Black soldiers at Chapin’s Farm in the fall of 1864, and I just imagine that as a moment that he promised to himself “I will never abandon you.” And he didn’t while others did. His political career after the war has often been treated as if he’s been fickle or that he was just about his own power. He always said “these parties are shifting around me and I’m clinging to these principles. I don’t care what the party’s name is.” That’s what you see in his correspondence: dump the Republican Party if they’re not going to help Black people.

CWT: What do you think was his biggest accomplishment?

EL: Refusing to return the three enslaved men who fled to Fort Monroe was a huge accomplishment in terms of what it meant to the enslaved people and as a prod to the federal government. You better come up with a policy for these enslaved people because they’re running away and we need to figure out how we’re going to handle this. His importance in holding Maryland, when the loss of Maryland would have been enormous. Then after the war, all of his work in Congress. He was involved in the Civil Rights Act, the KKK Act—and then as governor of Massachusetts also.

CWT: Would you like to comment on his conduct in the war? He seems to have been singled out for criticism.

EL: I think part of it is the New Orleans business. But when we think about the timing and the distance from Washington and the kind of situation he was confronting in New Orleans, I think he was doing the very best he could— and certainly some New Orleanians thought so too. I think he has been maligned even for his wartime experience not just by White Southerners but by White Northerners who didn’t like his attacks on the elite. As Whites in the postwar period North and South sought to make peace with each other to advance a certain vision of America, he was saying “No, no we have to lift up the poor, lift up these freedpeople, we have to protect the rights of black Americans.” He ticked a lot of people off, more than just his former enemies in the South. There’s a wonderful quote when he was running for president in 1884 and someone brings up the lingering resentment of certain white Southerners. He says, Well you know it’s true, when they were my enemy, I fought them tooth and nail, but they should know that when I am their friend, I will be equally their friend and won’t they be better off with me than with someone who says he is their friend but doesn’t really mean it. I am who I am, I will do what I say.

CWT: He supported William Mumford’s wife, the spouse of a man he executed for tearing down a U.S. flag in New Orleans.

EL: It is also completely forgotten that he watched out for her over the course of her life. I find him very charming and sweet with his grandchildren and little Ben. We forget how many people loved him so much and how many people he really did extend a hand to. He got kind of tired at the end of his life people asking him for money. Still, he maintained his commitment to high principles. He did believe there was a need for basic fairness and believed in people’s capacity to rise up and achieve, as he had done. And he saw that really slipping away. And it bothered him terribly. I think that is out of his own experience. I think he deserves his time in the sun.

this article first appeared in civil war times magazine

Facebook @CivilWarTimes | Twitter @CivilWarTimes

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.