Was the Trial of Billy the Kid Fair?

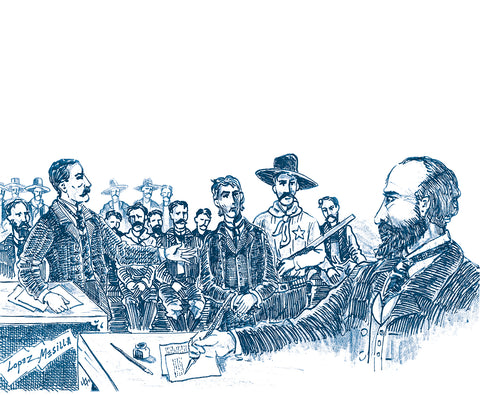

On Monday, March 28, 1881, Billy the Kid and Billy Wilson were escorted from their jail cells in Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory, to the train depot by Deputy U.S. Marshal Tony Neis and Police Chief Frank Chavez. Accompanying the lawmen and their handcuffed prisoners was attorney Ira E. Leonard. Though they were being transported to Mesilla, nearly 300 miles to the south, to face trial for serious crimes—the Kid for having killed Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady and Andrew L. “Buckshot” Roberts, Wilson for counterfeiting—the pair must have been elated at their relative freedom. They had been locked up in the Santa Fe jail for 91 days.

The southbound train went only as far as Rincon, some 30 miles shy of Mesilla. As the party disembarked, they were confronted by a mob of “roughs” who intended to wrest Billy from his escorts. Marshal Neis was able to shepherd the Kid and Wilson to a saloon across the street where he and Chief Chavez barricaded themselves and their prisoners in a back room. Neis, not knowing whether the mob intended to free or to lynch Billy, advised his prisoners that if the door were breached, his first action would be to “turn his guns loose” on them. Disinterested men on the outside eventually convinced the roughs to disperse.

Recommended for you

The next morning the party took the stagecoach to Mesilla, passing through Las Cruces. Hostile crowds were waiting at both places. On reaching their destination, Neis and Chavez turned over the Kid and Wilson to Doña Ana County Sheriff James W. Southwick, who placed the pair in the two-cell Mesilla jail, which already held 14 prisoners. The jail was within a high-walled placita. Forming one wall of the placita was the Mesilla Courthouse, which served as a primary school when court wasn’t in session. Katherine Stoes, a student the year Billy was tried, described the courtroom:

At the back end of the room is a small platform on which are a table and chair for the judge. On either side of the platform is a small table with two chairs. In one corner of the back wall is a large bookcase with the glass missing from one door. At the other corner is a stove in front of the fireplace. There is no other furniture in the room except 16 or 18 wooden benches without backs. In front of the desk was a small clearance where the lawyers came to make their pleas.

The jurors sat in the first two rows of benches. During deliberations they were cloistered in Joshua Sledd’s Casino Hotel, one block south of the plaza. Witnesses were also isolated there prior to their testimony. The court paid Sledd $2 a day for the use of his hotel, one of three in Mesilla at the time.

The Third District Court, in which the Kid and Wilson were to be tried, had jurisdiction over both federal and territorial cases. Court regulations required it to address federal business before territorial business, so each morning the court would open in federal session. After the federal business wrapped up, that session would adjourn, and the territorial session would open. The district magistrate, in this case Judge Warren Henry Bristol, presided over both sessions. Territorial lawyers sometimes served as prosecutor in federal cases and as defense lawyer in territorial cases, or vice versa. The court met six days a week, resting on Sundays.

The Kid appeared before Judge Bristol first thing on March 30 to face charges of murder and accessory to murder in the killing of Buckshot Roberts, who’d been mortally wounded on April 4, 1878, amid the Lincoln County War. The case was being pursued in federal court, as the site of the killing, Blazer’s Mill, was on the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation. Jurisdiction over reservations was limited to the federal government.

The Kid pleaded destitution, and Bristol appointed Leonard as his attorney. Leonard then asked the court for time to prepare Billy’s defense, and the court granted the motion. The next day, March 31, the Kid appeared before Judge Bristol and pleaded not guilty to Roberts’ murder.

On April 6 Billy’s trial for the murder of Roberts opened. At the suggestion of attorney Albert Jennings Fountain, Leonard moved Billy’s not guilty plea be withdrawn and the case dismissed, as the federal government lacked jurisdiction. Leonard argued that although Blazer’s Mill, the site of Robert’s killing, sat amid reservation land, the mill itself was on private land. Thus, the site fell under territorial jurisdiction.

Ira E. Leonard

Acting Attorney General Simon Bolivar Newcomb filed a demurrer, arguing while it was true the federal government lacked jurisdiction, that fact was irrelevant to the case. Judge Bristol overruled Newcomb’s demurrer, quashed the indictment and ordered Billy “go hence without delay.”

Of course, the Kid was not free to simply walk out of the courthouse. After granting a dismissal in the Roberts murder case, Judge Bristol remanded Billy to the custody of Sheriff Southwick to be held for trial in the killing of Sheriff Brady.

The next day, in federal session, Billy Wilson’s counterfeiting trial opened. Defense attorney Sidney Barnes (Leonard could not represent Wilson, as he had been subpoenaed as a witness against him) immediately requested a change of venue to Santa Fe, a motion opposed by Newcomb. Bristol agreed to send the case to Santa Fe.

On April 8, in territorial session, the Kid appeared before Judge Bristol to answer for the killing of Brady. He again pleaded destitution. Newcomb represented the territory, while the court assigned Fountain and John D. Bail as Billy’s lawyers. They pleaded not guilty on behalf of their client.

Billy the Kid became well acquainted with The Doña Ana

County Courthouse, the second building on the right, on the southeast corner

of the Mesilla Plaza. Inside, besides the courtroom where he was tried, were

the office of the sheriff, the office and residence of the head jailer and the

cell in which Billy was held.

Jury selection followed. The opposing sides went through the jury pool and three dozen talesmen before finding 12 mutually acceptable jurors. Almost all the potential jurors were Hispanic. An analysis of Fountain’s strategy shows he rejected the only four Anglos in the jury pool, suggesting he believed his client had a better chance with an all-Hispanic jury. The prosecution logged only six objections and found all four Anglos acceptable.

Census data gives us a picture of the jurors. They ranged in age from 27 to 56. All were married, except one widower. Six were farmers, and two were freighters. Five could not read or write. Territorial law required jurors to be male citizens, heads of families and between 21 and 60 years of age.

The Kid’s trial began the next day. The prosecution called four witnesses to testify against him—Jacob B. Mathews, Saturnino Baca, Bonifacio Baca and Isaac Ellis. Because no known transcript survives, it is necessary to reconstruct their testimony.

GET HISTORY 'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit

Mathews was one of four deputies walking down Lincoln’s main street with Brady on April 1, 1878, when the sheriff was killed. He would have testified about having suddenly come under fire and Brady getting hit, then sprinting to shelter and returning fire on the ambushers. Mathews would have identified the source of the firing as the corral of the late English rancher John Tunstall, who’d been murdered on Feb. 18, 1878. He would have recounted having seen the Kid and Jim French dash out from behind the corral and seemingly attempt to recover something from Brady’s body.

Saturnino Baca had been teaching school in the torreón, a fortress built in the 1850s for protection against Apache raiders, when Brady was killed. Bonnie Baca, Saturnino’s oldest son, had been in the street when the killing occurred. Both would have testified to having seen Brady fall and then the Kid and French run to the body. Ellis also would have testified to having seen Brady fall, as he was outside when Brady was shot.

No witnesses spoke in Billy’s defense.

The critical question is whether any of these witnesses had seen who fired the fatal shots. The answer is no. They knew the shooting came from behind Tunstall’s 10-foot-high corral wall (or gate in some accounts), but none was in a position to see the gunmen.

Behind the corral wall at the time of the shooting were eight men—Billy, French, John Middleton, Henry Brown, Fred Waite, Frank McNab, Robert Widenmann and Sam Corbet. Yet, strikingly, a grand jury had indicted only the Kid, Middleton and Brown for Brady’s murder. French, though spotted running from the corral with Billy to search the sheriff’s body, was not indicted. Did the grand jury have an evidentiary basis for selecting the trio, or did they just not know who else was behind the wall?

Many researchers have wondered whether Billy testified in his own defense. He did not.

The history of testifying in one’s own defense is surprising. Being able to tell one’s side of events when accused of a crime would seem a fundamental right. Yet it is a relatively recent legal right of a defendant.

Under English common law a defendant had no right to testify in his own defense, as he was presumed an incompetent witness due to self-interest. This was true for both civil and criminal cases.

After spending 91 days in the Santa Fe jail, Billy was

transported south for trial in Mesilla. The train only went as far as Rincon

(station pictured). There a mob either wanted to free or lynch the Kid. But

the next morning Billy and guards were able to continue by stagecoach.

As English common law formed the basis for U.S. law, defendants in the United States also had no right to testify in their own defense—at least initially. In the 1860s American legal scholars started to advocate for such a right. The first state to permit a defendant to testify in his own defense, in civil cases, was Maine, in 1864. Massachusetts followed suit in 1866, then Connecticut in 1867. Legal reformers then argued that defendants in criminal cases should be able to testify in their own defense. In 1869 New York became the first state to permit the practice in such cases.

In February 1880 the New Mexico Territorial Legislature passed a law permitting a defendant to testify in his own defense. Thus, Billy had the right to relate his side of the shooting to the jury. Why did he not?

Perhaps Fountain was so unfamiliar with the novel practice of having a defendant testify on his own behalf that he didn’t consider the option. The author has been unable to find any case prior to the Kid’s in which Fountain put a defendant on the stand to testify in his own defense. Or maybe Billy simply refused to plead on his own behalf—he had done it, Brady had deserved it, and he was not going to lie about it.

The latter explanation seems unlikely. At the time of Brady’s killing Fountain, founding editor of The Mesilla Valley Independent , had interviewed one of the men behind the corral wall (likely the Kid) and reported, “One of the murderers subsequently stated that Brady was killed by accident; that it was their intention only to kill [George] Hindman, as one of the murderers of Tunstall; and that one of the shots intended for Hindman took effect on Brady.”

With that statement Fountain had grounds to argue the killing of Brady had been unintentional. He could have called defense witnesses to bolster the argument. Corbet, among those behind the corral wall when Brady was shot, was in Mesilla during Billy’s trial. Why had Fountain not called him as a witness?

Following the witnesses’ testimonies and respective attorneys’ arguments, Judge Bristol presented the jury instructions for their deliberation. This was the decisive moment of the trial.

Territorial law required that to convict a defendant of first-degree murder, the jury must be certain beyond a reasonable doubt the defendant did it and equally certain the act was intentional.

Fountain prepared instructions to the jury that explained and emphasized these two requirements. Bristol rejected those instructions. Instead, he presented the jury with three pages of dense instructions of his own, instructions that, as far as the author has been able to determine, were longer than any presented to a jury by Bristol during his judgeship.

Regarding the requirement they be certain the defendant had killed Brady, Bristol told the jury that even if they did not believe the Kid had fired the fatal shot, they could still find Billy guilty for having encouraged, incited, aided in, abetted, advised or commanded the killing. As none of those actions could be proved without the testimony of a participant in conversations preceding the shooting, that part of Bristol’s instructions was irrelevant, its purpose seemingly to confuse the jury.

Regarding intention, Bristol instructed the jury this way:

As to this premeditated design, I charge you that to render a design to kill premeditated, it is not necessary that such design to kill should exist in the mind for any considerable length of time before the killing.

If the design to kill is completely formed in the mind but for a moment before inflicting the fatal wound, it would be premeditated, and in law the effect would be the same as though the design to kill had existed for a long time.

In effect Bristol asserted the intention to kill need exist for only a “moment” to qualify as premeditation. Such a definition of intention would qualify almost every crime as premeditated.

Saturnino Baca

Bristol had his complex instructions read to the jury in English and then given to them in written English for use in their deliberations at the Casino Hotel. Yet few of the jurors (perhaps none) spoke English. The editor of Newman’s Semi-Weekly , a short-lived Las Cruces–based newspaper, addressed a similar oversight regarding the conviction of Frank C. Clark for first-degree murder in the same court session:

We desire to call the attention of the court and bar to the manner in which trials are conducted in this county through the medium of interpreters.…We on Thursday watched for several hours the progress of the trial of Clark for murder. Here was a man being tried for the highest crime known to the law; his life hung in the balance, and he was certainly entitled to all the protection and all the guaranties which the court and the laws of his country could throw around him. He was entitled to an impartial trial; and in this term “impartial” is embraced the right of his attorneys to advance and explain any theory of the case which they might consider would relieve him of the terrible suspicion resting upon him. If their theory is not thoroughly and lucidly explained, and the abstract principles and ideas advanced by them are not interpreted to the jurors in a manner to be perfectly understood by them, then it appears to us that Clark has just ground of complaint that a fair trial has been denied him. We maintain that this was not done; and any Spanish scholar who watched the proceedings will bear us out.

There is reason to believe such obstacles to a fair trial were also a factor in the Kid’s trial. If such obstacles did exist, his trial would be viewed today as a mockery of justice. On April 9, 1881, the jury found Billy guilty of Brady’s murder.

Almost every author who has written about the Kid and the Lincoln County War has questioned why there is no surviving transcript of Billy’s trial. Most have speculated that either no transcript was made or else the transcript was lost or stolen.

In fact, the court clerk would have made a transcript, as territorial law mandated the transcription of trial proceedings. But another rule of the court was that if attorneys did not appeal a case, the court would not pay a clerk to make a formal copy for the case file, as that would have been considered an unnecessary expense.

On April 13 Billy returned to court to learn his fate. Judge Bristol sentenced him to hang “by the neck until his body be dead,” on May 13, “between the hours of 9 of the clock in the forenoon and 3 of the clock in the afternoon.”

Billy had several grounds on which to appeal his conviction. One was that Bristol had given the jury its instructions in English, though none of the jurors could read or necessarily speak English. Another was that Bristol had instructed the jurors they could only consider first-degree murder or acquittal. Territorial law recognized five degrees of murder, and had the jury been permitted to consider all options, they likely would have convicted Billy of a lesser charge. Over the next 18 months defendants convicted of first- degree murder would appeal their convictions on both of these grounds.

The 1850 building on the Mesilla Plaza that once served as

the Doña Ana County Courthouse and jail now houses the Billy the Kid Gift

Shop. After the county seat was moved 5 miles north to Las Cruces in 1882, the

county sold the building to the town.

Fountain filed no appeal for the Kid, however, as Billy lacked the money to pay for one. Territorial law required the state to pay for a destitute defendant’s legal representation in a trial, but not for an appeal.

On April 16, three days after his sentencing, an escort of six men—Bob Olinger, David Wood, Daniel Reade, Tom Williams, Billy Mathews and John Kinney—loaded the Kid into an ambulance (wagon) for transport to Lincoln. “[Billy] was handcuffed and shackled and chained to the back seat of the ambulance,” reported Newman’s Semi-Weekly. “Kinney sat beside him; Olinger on the seat facing him. Mathews faced Kinney …and Reade, Wood and Williams [were] riding along on horseback on each side and armed to the teeth.”

They were transporting the Kid to Lincoln to hang because territorial law mandated a defendant sentenced to death be hanged in the county in which the crime was committed. On April 21 Billy’s escort delivered him into the custody of Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett.

Seven days later the Kid escaped from jail at the Lincoln County Courthouse, killing Deputies Olinger and James Bell in the process. On July 14, at about midnight, Sheriff Garrett fatally shot the Kid in friend Pete Maxwell’s bedroom at the latter’s family ranch in Fort Sumner—62 days after Billy would have died by hanging.

Based in Las Cruces, N.M., David G. Thomas is a historian, filmmaker, producer, actor, screenwriter and travel writer. Thomas wrote the feature “He Shot the Sheriff,” about the killing of Pat Garrett, in the February 2021 Wild West. He adapted this article from his 2021 book The Trial of Billy the Kid , part of his Mesilla Valley History Series.