Tormenting Tories: How American Rebels Ran Loyalists Out of Town

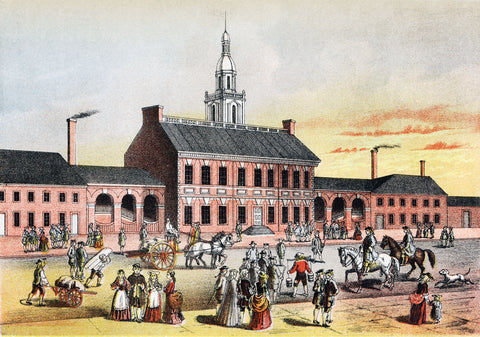

Fists banged on Grace Galloway’s front door early on the morning of Thursday, August 20, 1778. From the entryway where she and a servant had been awaiting unwanted visitors to her stately home at Market and Sixth Streets, a block from the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, Galloway shouted that she would not be admitting anyone. Her callers, all male, circled the house trying every door, finding each locked. Using a scrubbing brush, the men stove in the kitchen door. Red-faced and short of breath, the intruders rushed to where Galloway stood. First among the raiders was Charles Willson Peale, an artist and fervent American Patriot who that day was acting in his official role as a commissioner in charge of confiscating property from foes of the Revolution. Peale and companions had come to evict the Galloway family.

On the Outs. Dedicated

Loyalists had to be prepared to undergo rude searches, harassment, and much

worse. (Granger, NY)

The city’s so-called commissioners for forfeited estates really were out to punish Grace’s husband Joseph, a prominent politician who had aided the British army during its recent occupation of Philadelphia. When in recent months the army pulled up stakes, Joseph had fled. Peale had warned Grace on Wednesday that he would be coming to take possession of the Galloways’ Philadelphia home. Face to face with Peale and his men, Galloway declared that “nothing but force should get me out of my house,” she wrote later in her diary. One interloper said he knew how to deal with that: They would throw her clothes into the street. Onlookers, including friends of Galloway’s, appeared. After a while a carriage arrived for Galloway, and one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest women reluctantly walked out to join tens of thousands of Americans dispossessed by the Revolution.

A Woman

of Wealth and Taste. Grace Galloway moved comfortably among the upper strata

of colonial Philadelphia society, but the Revolution knocked her family for a

loop. (Wiederseim Associates)

Sparked by hated new taxes, hostility to Britain had emerged and spread rapidly in the Crown’s North American colonies in the decade before the colonies declared independence. But only about 40 percent of their 2.5 million inhabitants ardently desired independence. Another 40 percent were on the fence. About 20 percent, known as Loyalists or Tories, wished to remain part of Britain. Not only were Patriots waging war against the world’s mightiest empire—they were conducting a campaign to bring along Loyalist neighbors, whether by persuasion or by violence. Patriots whipped up mobs, confiscated property, and forced Loyalists into exile. Many Loyalists fought back in armed militias or in the British army. But in nearly any area lacking a sizable British military presence, zealous Patriots gained control of local government and stamped out dissent. Grace Galloway’s diary and letters provide a window into the experiences of this internecine conflict’s losing side.

A merchant’s daughter , Grace Growden married Joseph Galloway, an up-and- coming Philadelphia lawyer, in 1753. Upon their father’s death, Grace and her sister Elizabeth inherited multiple estates covering thousands of acres of property collectively valued at more than £110,000. Grace bore several children, but only one, also named Elizabeth, survived infancy. Joseph’s career took off. Elected to the Pennsylvania assembly, he served as that body’s speaker from 1766 to 1775, during which period onerous new colonial taxes prompted widespread rioting, attacks on symbols of British authority, and bans on British imports.

Charles Peale

(Philadelphia Museum of Art)

When the colonies convened the First Continental Congress in 1774 to coordinate resistance, Galloway attended as a member of the Pennsylvania delegation. Decrying the new taxes but fearing a bloody, futile confrontation, he proposed converting the Congress into an American parliament with power to block British legislation affecting all the colonies. Congress, voting colony by colony, rejected Galloway’s plan by a single vote, opting instead for a comprehensive trade boycott.

To enforce that boycott, Congress created local committees. These bodies forcefully cracked down on attempts to sidestep the bans and gradually took over local militias and other functions of governance. Such hard line tactics alienated moderates like Galloway, who stayed away when Congress convened again in May 1775. The colonies hurtled toward a declaration of independence and the carnage he had predicted. A little over a year later, Galloway crossed over to the British side to offer his services, and when General William Howe occupied Philadelphia in September 1777, he made Joseph Galloway his chief of police.

Within the year, forced to reassign troops due to France’s entry into the war, the British had pulled out of Philadelphia. Soon, so had Joseph Galloway, taking daughter Elizabeth with him to New York. Grace stayed behind to try to protect their holdings. The commissioners for forfeited estates came calling to say they would be seizing these properties, many of which she had inherited from her father, and evicting her from her Philadelphia home. Aided by powerful friends, Galloway appealed to the Pennsylvania Executive Council. The council replied that a wife automatically ceded to her husband ownership of property she brought into the marriage. Should a husband prove treasonous, the state could seize his holdings, with title reverting to his widow or her heirs following his death. On August 19, Peale gave Galloway until 10 the next morning to vacate her home.

Joseph Galloway

(New York Public Library)

The reality of eviction distressed Galloway but left her relieved that the protracted tussle had ended and hopeful that she would recover her property. She moved in with her friend Molly Craig and her husband, noting in her diary that after lunch they visited other friends. “I did not seem to be much concerned,” she wrote. Benjamin Chew, a former chief justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania who had urged Galloway to fight her eviction as unlawful, advised her to sue the commissioners of forfeited estates, alleging illegal forced entry. Galloway demurred. At the end of her diary entry for that day she wrote, “I am just distracted, but glad it is over.” Still, her newly reduced circumstances chafed. “People are soon tired with intruders,” she wrote, adding later, “Mrs. Craig I think is tired and what she does is really through charity.” Her hosts’ own political divisions complicated the situation. Mr. Craig was a “strong” Patriot, Mrs. Craig a “violent” Loyalist. After two months, Galloway began bunking with her friend Debbie Morris. One evening, walking to Morris’s home, Galloway saw her former carriage pass by—a reminder of all she had lost. “My dear child came into my mind and what she would say to see her mamma walking 5 squares in the rain at night like a common woman and go to rooms in an alley for her home,” Galloway wrote in her diary.

In New York City, the hub of the British war effort, Joseph and Elizabeth Galloway were poised to sail for London. As they waited they corresponded frequently with Grace in secret, smuggling letters in pen quills and other hiding places. Patriot authorities, who sometimes expelled Philadelphians after intercepting messages residents had sent containing information deemed to be of military value, intercepted an affectionate farewell note Joseph Galloway had sent his sister and published the contents in local newspapers.

A Spouse’s

Dilemma. Joseph Galloway had to flee his hometown for his life because he

had sided with the Crown. He and his wife smuggled letters to one another.

(New York Public Library)

“It did him no dishonour,” Grace noted in her diary, though the episode unsettled her. In an early letter to Grace, Joseph Galloway asked if her hardships were as he had heard them described, and, if so, urged her to come to New York. She refused, citing their daughter’s welfare. “Should I leave this place…then perhaps, my dearest child may become a beggar,” Grace wrote of Elizabeth. “Therefore, while I have the least shadow of saving something for her, I will stay.”

Her daughter’s absence tore at Grace. “My child is dearer to me than all nature and if she is not happy or anything should happen to her, I am lost,” she wrote in her diary. “Indeed, I have no other wish in life than her welfare.” Joseph’s welfare, less so. It came to Grace that she didn’t miss her husband, recalling him as imperious and unkind. “The liberty of doing as I please makes even poverty more agreeable than any time I ever spent since I married,” she wrote that November. “I want not to be kept so like a slave as he always made me in preventing every wish of my heart.” As she grasped that his financial arrangements were making her life more difficult, her rancor grew. The state now controlled the Galloway holdings, but some tenants still paid her rent—except those with whom Joseph had made side deals. One man told her that at her husband’s request he had advanced him £400 in rent before Joseph left town. “This unhappy man has ruined himself and I find he conceals all he can from me,” Grace wrote of her husband. “His base conduct with me when present and his taking no care of me in his absence has quite made me indifferent toward him.”

Grace’s diary entries for late 1778 often cite health problems. Christmas Day was snowy and extremely cold, and Galloway noted her pleasure at having been able to procure firewood. She sat alone most of that afternoon, sleeping. “Am so unwell can hardly keep up,” she wrote in her diary. On New Year’s Day she summoned doctors. “Before they came, I was taken with a puking and found it was a true bilious colic,” she wrote. “By the time the doctors came, I got ease; but they all thought me in a dangerous way. Oh, my dear child, how did I then think of you…I got up in the evening and was better but continued ill for many days after.” Mostly bedridden through February, she ignored her diary until March.

this article first appeared in American history magazine

Facebook @AmericanHistoryMag | Twitter @AmericanHistMag

Lonely, impoverished, and ill, Galloway relied for aid on a robust network of friends. Colonial-era America was a close-knit society, and among Philadelphia’s upper classes, personal history seems to have prevailed over current-day politics. Galloway’s diary frequently refers to meetings with friends, some of them such prominent Patriots as Continental Congress delegates John Dickinson and Elias Boudinot. But wariness was afoot. Many in her circle hesitated to have Galloway in their homes, a harsh turn for a person of once exalted standing.

Men of her acquaintance, especially, worried that receiving an accused traitor’s wife could raise community eyebrows.

“Why must I have people by dozens that will not get me to their houses but let me dine at home; so that I can give them a dish of tea tis all they care,” she wrote. “The whole town are a mean pack.” Some friends grew standoffish.

A Fond Welcome. A 1783 print portrays steadfast

Loyalists being greeted as they arrive in Britain after the Revolution.

(Granger, NYC)

Benjamin Chew, initially solicitous, became less willing to help with her legal troubles, and Galloway noted with disgust that Chew and family, despite their Loyalist sympathies, consorted with French officers and radical Patriots. “I know [the Chews] are no friends to me and mine,” she wrote. “Chew is for keeping in [with] both sides but suspected by all.”

Meetings with friends offered a much-needed opportunity to vent frustrations. “I told them I was the happiest woman in town, for I had been stripped and turned out of doors, yet I was still the same,” Galloway wrote after one such encounter. “It was not in their power to humble me, for I should be Grace Growden Galloway to the last…that if my little fortune would be of service to them, they may keep it, for I had exchanged it for content.” Ranting brought her happiness, though she noticed one witness wincing. Sometimes Galloway worried in entries that she should show more caution. Shocked to discover in conversation that a friend was a Patriot, she worried afterwards that she might have said something improper to the woman. “[I] am vexed about Sally Zanes,” she wrote. “I wish I could always be on my guard.” One night after a gathering at which she feared she had said too much, she awoke in a fright. “I dreamed I was going to be hanged,” she recorded in her diary.

Signed public oath of allegiance to the

monarchy. (Hum Images/Alamy Stock Photo)

Loose talk of Loyalist ideas could be dangerous. Patriots generally imprisoned and executed only individuals who aided the British war effort—which fate might have befallen Joseph Galloway had he remained in Philadelphia. A lesser but still horrifying punishment, tarring and feathering, involved stripping accused individuals bare and slathering them in molten tar topped with a coat of feathers, then parading the unfortunates through the streets. In May 1779, shortages of many basic goods in Philadelphia prompted rioting by Patriot militia and violence against Loyalists. “A mob is raised in the town, and they are taking up Tories,” Galloway said in her diary. “I was much alarmed…We put away our valuable things thinking they will search the house for [flour] and stores.” Rioters demanded that all Loyalists be expelled from the city. “I am afraid to be sent away,” Galloway wrote.

A couple of months later, authorities advertised Galloway’s estate for sale in local newspapers. Galloway, who had been thinking of sailing to London to find Joseph and Elizabeth, agonized over whether to make a new claim on her properties or try to buy them back. She feared this could amount to acknowledgement of Patriot authority, risking charges of treason or wrecking her reunion plans. Friends and acquaintance gave conflicting advice. Patriot authorities “knew they had no right to my estate, and that I would not ask that as a favour, which I had a right to command,” she wrote in her diary, “and that I never did or would acknowledge their authority, as I was an Englishwoman.” Upon reflection a few days later, she wrote, “I am yet undetermined how to act. I think it best to leave it, but my child’s interest argues for buying…I am almost out of my wits.” Merchant Abel James offered to buy a couple of Galloway properties being auctioned and hold the parcels in trust for her to preserve stands of trees—a valuable source of firewood. She gratefully accepted, but James was outbid.

Pledging Allegiance—To

the King. Many colonists who fervently believed in the Crown signed public

oaths of allegiance to the monarchy, above. These recorded displays of fealty

sometimes meant that it was best for signatories to get out of town, left,

when British armed forces retreated. (Granger, NYC)

Through early 1780, Philadelphia newspapers carried notices of sales of Galloway properties. By now many prominent Loyalists had left town, their downtown mansions occupied by new owners. Executive Council President Joseph Reed was living in the Galloway house. Deteriorating health forbade Grace to travel to London and smuggling missives had become difficult, but she continued to write letters to Elizabeth that she hoped to show her daughter one day. In one of the last, Grace Galloway wrote, “It is now going on three years since I was left in this dreadful situation, and my health now so impaired that I never hope to have it in my power to see my relations or native country more. Want of health and to save your inheritance alone detains me. If by it, I save my child, all will be right.” She died on February 6, 1782. She was in her fifties.

The war was winding down. A decisive defeat at Yorktown in October 1781 prompted the British to begin negotiating with the Americans and withdrawing their troops. The crown maintained a strong sense of responsibility toward the faithful who had stood fast. Decamping from Charleston, Savannah, and New York City, British troops took with them tens of thousands of Loyalists who feared for their safety. During the war, at least 60,000 Loyalists fled the former colonies, mostly relocating in other parts of the empire. The Peace of Paris signed on September 3, 1783, committed the Americans to ending persecution of Loyalists and returning their property. Initially authorities mostly ignored that mandate, as Elizabeth Galloway discovered when from London she began to try to recover her mother’s estate. But over the years Pennsylvania authorities allowed Elizabeth to gain ownership of most of the family properties. The state dropped any claim to the Galloway estate when Joseph Galloway died in 1803, 26 years after Grace Galloway’s eviction.

Forced Out

In their high stakes bid for independence, American Patriots, unwilling to tolerate potential enemies in their midst, made Loyalist neighbors choose: Change sides or leave. These efforts gained steam after the First Continental Congress in 1774. Patriot committees and mobs, and later state legislatures, required that citizens renounce the Crown and swear allegiance to their states of residence. Those who balked first suffered social and economic isolation and, if they persisted, physical attack and property confiscation. Eight states banished prominent Loyalists, threatening execution if they returned.

Hitting the Road. Neighbors’ ire and

governmental pressure propelled many Loyalists out of their homes and into an

uncertain future elsewhere. (Granger, NYC)

This treatment spurred many Loyalists to flee, first to British-held areas such as New York City and after the war elsewhere in the empire. Men branded traitors often left behind wives and children in efforts to hold onto property otherwise apt to be seized. Sometimes authorities allowed wives to retain such property, or at least portions thereof. This apparently was what the Galloways were hoping for when Grace stayed in Philadelphia, though husband Joseph’s notoriety probably precluded any leniency toward Grace Galloway.

The largest number of émigrés went north to Quebec and Nova Scotia, where the British helped them resettle with free land, seed, tools, and provisions. Others went to Great Britain, where authorities started paying refugees pensions and offering compensation for their losses. In 1783, Parliament established a commission in London to hear Loyalist claims. Before the evacuation of British troops and Loyalist residents from New York City that same year, commission representatives traveled there, as well as to Quebec, Montreal, St. John, and Halifax, to allow refugees to file for compensation. By 1788, a total of about £3 million had gone to more than 4,000 claimants. One was Joseph Galloway, granted £500 a year. Galloway initially remained active in politics, advising the British government on policy toward its rebellious American colonies and writing pamphlets on the subject.

At a parliamentary inquiry into the conduct of the former head of the British war effort in America, William Howe, Galloway criticized Howe for neglecting to make more and better use of Loyalist civilians to reassert British control and of alienating disaffected colonists by failing to rein in his troops’ excesses. —Jonathan House

This article appeared in the Autumn 2022 issue of American History magazine.

GET HISTORY 'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit