Thespians in Chief

Americans have finally found a politician they can admire—Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. Since Russia invaded his country on February 24, 2022, Zelensky has blanketed the news, a model of patriotism, toughness, humanity, even humor. Whether inspiring his people, mourning the dead, or lecturing the world, Zelensky has seemed made for his moment.

He prepped for his job by playing it on Ukrainian television. From 2015 to 2019 he starred in Servant of the People , a satirical series in which a high school teacher gets elected president after an anti-corruption rant he delivers in class goes viral. In 2019 the entertainer ran for president for real and won.

Americans of all people should not be surprised by the arc of Zelensky’s career. Our 40th president, Ronald Reagan, starred in Hollywood before he ascended to the White House. But he was not the only American politician to savor and master the dramatic arts. As biographer Noemie Emery put it, Reagan was not our first actor president—though he was the first to have acted in movies for money.

The first thespian-in-chief was that figure of so many firsts, George Washington. He brought several sets of skills to his role as America’s leading man. First was a fan’s appreciation of the craft. Washington had a lifelong love of the theater, soaking up any performance that came his way, from puppet shows to Shakespeare. Theatrical metaphors dot his writing.

At the end of the Revolutionary War, in a letter to Lafayette, Washington compared his new country to an actor “treading this boundless theater”—that is, the world stage. On his last day as president, writing to Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull, Washington compared himself to an actor about to make his exit: “The curtain drops on my political life…this evening, I expect for ever.”

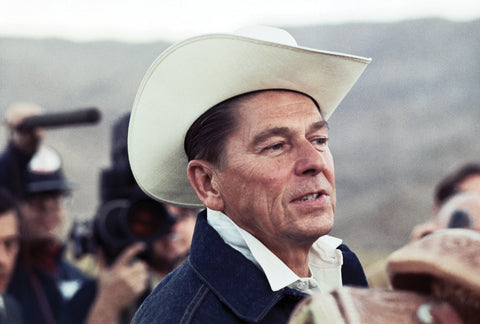

When

in Doubt, Act the Leader. George Washington, here on July 15, 1776,

accepting command of the Continental Army, long harbored an appreciation for

dramatics. (MPI/Getty Images)

Washington lacked certain qualities we associate with performers—he was neither eloquent nor witty—but he brought other natural endowments to the job. He was tall and imposing, assets he emphasized with his posture, his composure, and, as a soldier, his uniforms, typically of his own design. His presence astride a horse—where most people saw him—enhanced the overall effect. Thomas Jefferson, himself no mean equestrian, called Washington “the most graceful figure that could be seen on horseback.”

Washington made use of the late 18th century’s understanding of the word character.

We think of character, good or bad, as internal. But to Washington and contemporaries, character was how you carried yourself. Character was “a persona that one deliberately selected and always wore,” historian Forrest McDonald explained. “If one chose a character that one could play comfortably and played it long enough and well enough, by degrees it became a ‘second nature.’” Every man—and woman—was a character actor. Washington simply was aiming to get top billing.

Abraham Lincoln, like Washington, was a playgoer. He adored Shakespeare and was of course murdered at the theater—by an actor (see “Killer Cousin,” p. 58). But Lincoln had to adapt the role of president to his own talents—and lack thereof. He did not obviously look the part. He was tall and strong but his frame was gangly, topped by a face as homely as a shovel, especially after he grew that unfortunate beard.

Like many a funny-looking person, Lincoln decided early on to be funny, and became a master storyteller known for his humorous bits. He learned at home: his father Thomas, whom young Abe did not particularly like, was a fine yarn spinner. Lincoln the lawyer used stories to win over juries, and as a politician to woo audiences, repeating some tales so often they were known as Lincolnisms. He also used loquacity to keep people at bay. Leonard Swett, an Illinois crony, described him fending off importuning jobseekers during the interval between his first election and his first inauguration: “He told them all a story, said nothing, and sent them away.”

this article first appeared in American history magazine

Facebook @AmericanHistoryMag | Twitter @AmericanHistMag

As he entered middle age, and the country entered the home stretch to civil war, Lincoln still used humor—his favorite answer to Democratic charges that the new Republican party believed in race mixing was that just because he didn’t want a Black woman for a slave did not mean that he wanted her for a wife: he could just leave her alone. But he also began to rely on elevated rhetoric drawn from Shakespeare and the Bible. Lincoln was no orthodox Christian, but like every Protestant American he had been reading and hearing the King James Version all his life. By the time he reached the White House he could channel it, from musical effects (the Gettysburg Address phrase “four score and seven years” echoes Psalm 90, “the days of our lives are three score years and ten”) to expatiating on the Almighty’s will (his Second Inaugural address offered a war-torn nation Psalm 19: “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether”). In our time, actor Jim Caviezel has played Christ; Lincoln could play God the Father.

Franklin Roosevelt made his run for the White House in a wheelchair, albeit one concealed from the public. He brought to his auditions a good profile—the dime carrying his image is our most attractive coin—and a million-dollar smile: just what America needed in the depths of the Depression. FDR also brought a melodious tenor voice, well suited to the new medium of radio. His accent—an amalgam of New England r-dropping (he was a Groton/Harvard alum) and haute WASP pseudo- Brit—strikes our ears as too theatrically rich by half. But listeners of his time heard the tones of a genial aristo. FDR emphasized the friendliness by using simple constructions and contractions; one speechwriter who helped him dial it down was Broadway scribe Robert Sherwood. Radio itself made FDR seem friendly: he called his periodic addresses “fireside chats” because they came into homes through consoles by his listeners’ firesides—or stoves, or radiators.

One of Roosevelt’s last performances was a live marathon. His fourth run for president in 1944 was dogged by rumors about his ill health. To refute the chatter, he made an all-day campaign swing that October in an open car, in pouring rain, through four of New York City’s five boroughs, ending with an appearance at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. A mid-ride change of clothes and a shot of bourbon kept him going. He died six months later; the rumors of bad health had been true. But only after he had won his race.

Our most recent performer president was Donald Trump. Unlike Zelensky, Trump never played a national leader. But he did play a CEO on 14 seasons of The Apprentice —a run which, along with his last-century books on his career as a real estate mogul, accustomed Americans to him being presented as being in charge. No matter that his real estate deals often went sour or that The Apprentice dealt in scripted stakes: the show went on. Zelensky won Ukraine’s presidency as a corruption fighter. He now finds himself fighting a sadistic superpower. The role of a lifetime may become the role of his deathtime. In real life, scripts change without warning.

GET HISTORY 'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit