The Turkestan Incident

On June 2, 1967, with Wing Commander Colonel Robert Scott away, Colonel Jacksel “Jack” Broughton was serving as acting commander of the United States Air Force’s 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, based at Takhli, Thailand. Broughton had flown a strike mission into North Vietnam that day and, after landing, he went to his office to catch up on paperwork and then headed to the officers’ club for dinner. As he ate, two pilots—Majors Frederick G. “Ted” Tolman and Alonzo “Lonnie” Ferguson—asked to talk to him. They knew Broughton was someone who listened to and cared about his pilots, and they wanted to discuss the mission they had just flown.

Tolman related what had happened. He and Ferguson had been piloting Republic F-105 Thunderchiefs that day, with the call signs Weep 3 and Weep 4, Tolman flying lead and Ferguson as wingman. Their mission was to fly through Route Pack 6, a heavily defended corridor over North Vietnam, and bomb a railroad junction. Along the way, Tolman and Ferguson had flown over the North Vietnamese port of Cam Pha.

When Majors Frederick Tolman (left) and Alonzo Ferguson

(right) inadvertently strafed the ship in Cam Pha harbor, they kicked off a

diplomatic incident and left themselves open to charges.

Like the larger harbor of Haiphong 40 miles to the southwest, Cam Pha had been placed off limits for American attacks under the Rules of Engagement (ROE) set by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara for Rolling Thunder, the tactical bombing of North Vietnam. President Lyndon B. Johnson and McNamara both wanted to avoid any military actions that might “widen the war,” as McNamara put it. That meant avoiding anything that could bring Red China or the Soviet Union into direct warfare with the United States. Soviet ships were on the forbidden list, even if they were known to be delivering MiG fighters and surface-to-air missiles that would be used against American aircraft.

As the two pilots passed over Cam Pha, their “Thuds” became the target of anti-aircraft fire. They did not fire back but continued on toward their target, although Tolman—“an aggressive, hard-hitting pilot,” as one contemporary described him—said he made a mental note of the AA locations and decided he would make a strafing pass on the return leg.

After hitting their target and heading for home, the pilots flew back over Cam Pha and encountered heavy fire again. With Tolman in the lead, the two Thuds made a diving strafing run at the batteries with their six-barreled Vulcan 20mm cannon. At an airspeed of more than 400 knots, the strafing run lasted mere seconds. As their cannon shells tore into the line of AA emplacements, Tolman suddenly noticed a ship anchored in the harbor that was directly in his line of fire. Instinctively he centered his gunsight on the vessel and loosed a short burst.

He and Ferguson pulled up, streaked over the ship and resumed their flight. A storm forced them to land at the auxiliary base at Ubon, where they were debriefed while waiting for the weather to clear. By then Tolman realized the ship he had fired on was probably Soviet and he understood the implications of his actions. He told his debriefers about the AA barrage, but that he and Ferguson had not returned fire, a false statement that went on the official record. Ferguson did not contradict Tolman’s account, further muddying the issue. Once back at Takhli, the two pilots decided to ask Broughton for advice.

Left: An aerial

photo shows the situation Tolman and Ferguson faced above Cam Pha Harbor on

June 2, 1967. Their attention was focused on the anti-aircraft emplacements.

Right: The two pilots passed over Cam Pha on their way in and out of North

Vietnam.

Colonel Jack Broughton was 42 years old and a graduate of West Point’s class of 1945 who had flown 114 missions during the Korean War and later commanded the Thunderbirds, the Air Force’s demonstration team. He would fly an additional 102 missions in Vietnam. As vice commander of the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, Broughton seemed like perfect image of a combat fighter squadron leader. “Colonel Broughton was a large man with a square-set jaw, stern eyebrows, and close-cropped hair, which he brushed straight up from his forehead,” wrote Ken Bell in 100 Missions North: A Fighter Pilot’s Story of the Vietnam War. “He exuded confidence, with just a trace of danger.” Broughton had planned and led bombing missions to destroy key North Vietnamese Army sites along Route Pack 6, and many of those flights passed over or around Cam Pha and Haiphong. Subordinates and superiors alike considered him an excellent leader and pilot. He also had a withering contempt for the civilian and military managers in Washington and the restrictions they forced pilots to observe, which Broughton later called “probably the most inefficient and self- destructive set of rules of engagement that a fighting force ever tried to take into battle.” Broughton listened to Tolman and Ferguson and gave the matter serious thought. If Tolman or Ferguson had started their cameras before opening fire on the AA emplacements, the footage would show whether they had fired at the Soviet vessel. By this time the film had been removed from the airplanes and was waiting to be flown out by a courier aircraft to another base for processing. As Broughton later wrote, “I could either follow the established procedures and they would be court-martialed for firing on an unauthorized target and making false official statements, or I could do something about it.”

An image from

newsreel footage shows damage to the Turkestan, but the cause remained in

doubt.

Broughton decided he would do something about it. He called the duty sergeant at the photo lab and had him bring the undeveloped film canisters to him. Together they opened the canisters and exposed the film with the lab truck’s headlights. This was certainly against all the rules, but Broughton already disagreed with many of the ROE he and his pilots were forced to follow. His men had to face real guns and real missiles, not paper evaluations written up in some Pentagon office 12,000 miles away. “I could have let that film go through its normal channels and thrown Ted and Lonnie to the wolves,” he said. But that was not Jack Broughton’s way. “As far as I was concerned, nobody could ever establish firmly that we had done any damage to a ship that was delivering weapons to be used against us.” After telling Tolman and Ferguson what he had done, he told them to get some sleep. They would resume flying missions as usual.

Broughton was betting that the incident would blow over. He was wrong.

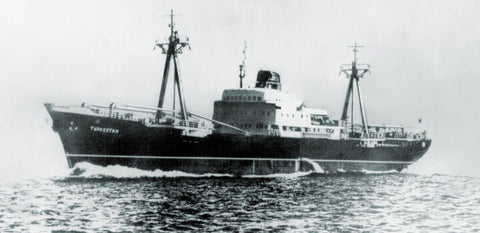

The vessel that Tolman and Ferguson had seen at Cam Pha was a Soviet- registered freighter named the Turkestan. After the incident, its caption radioed his superiors in Hanoi, claiming that two American fighters had fired on his ship without provocation, causing great damage and killing one of his crew. The report immediately went up the chain of command to the Soviet Foreign Ministry in Moscow. The Soviet Union issued an immediate protest of the incident, which it termed “a criminal violation of the freedom of navigation, an act of banditry which may have far-reaching consequences.” The Soviets claimed to have recovered an “unexploded” 20mm shell from the damaged ship.

By the following day, Johnson and McNamara had been briefed about the incident, but the Pentagon noted suspicions about the evidence the Soviets claimed to have. The Thunderchief’s 20mm cannon did not eject its spent shell casings or unfired rounds. Instead, the casings fell into a bin under the Vulcan cannon for recovery after landing. The only way the Soviets could have an unfired shell was if they had recovered it from one of the more than 140 F-105s that had been shot down the previous year. The Pentagon explained this to the White House, and for a short time the situation seemed to be losing steam.

That day the U.S. Government responded that the attacks had taken place but “only against legitimate military targets” and that it was “North Vietnamese anti-aircraft fire that had struck the Soviet vessel.” But since there had not yet been an official investigation, the U.S. government assured Moscow that an investigation would be conducted immediately.

President Lyndon Johnson (center) and Secretary of

Defense Robert McNamara (right) were determined not to widen the war in

Vietnam by antagonizing the Soviet Union, and as a result paid close attention

to the Turkestan incident. Secretary of State Dean Rusk is at left.

The 355th went on flying its missions and losing pilots to Soviet-manufactured SAMs and AA fire. But having heard nothing more of the Turkestan incident, Broughton thought he had put it behind him. He realized he hadn’t on June 17, when General John Ryan, the commander-in-chief of the Pacific Air Forces (PACAF), arrived, ostensibly to inspect the base and get briefed on the progress of Rolling Thunder. He had also been told by the Air Force’s vice chief of staff, General Bruce Holloway, to get to the bottom of the Turkestan affair. To avoid giving Broughton and the two pilots any chance to coordinate their stories, Ryan had not told them he was coming to conduct an investigation.

Ryan arrived on his personal aircraft, accompanied by a large entourage, most of it made up of Air Force investigators. After going through the motions of listening to briefings and assessments, Ryan lowered the boom. He had every person even remotely connected with the matter brought in for rigorous questioning. Ryan raked Broughton over the coals, demanding to know the truth about the incident. After spending days grilling every person involved, Ryan declared that a court-martial was in order. Broughton, Tolman and Ferguson were about to face a trial that would decide their careers and possibly their freedom.

Then the White House, hoping to defuse the situation, issued a statement on June 20. “The United States formally expressed regret today for damage to the Soviet cargo ship Turkestan off the North Vietnamese port of Cam Pha and gave assurances to Soviet authorities that every effort would be made to ensure that such incidents do not occur again,” the statement read. The White House did not mention the possibility that the ship’s crew had fired on the F-105s, and that the pilots might have been reacting in self-defense.

Shortly afterward, the Navy experienced its own similar incident. On June 29 two Navy fighters attacked the Soviet ship Mikhail Frunze in Haiphong harbor. The Defense Department announced that damage to the ship was “inadvertent,” and the matter ended there. Unlike the Air Force, the Navy had no plans to prosecute its pilots for violating the ROE.

Broughton, Tolman and Ferguson were brought up on charges written up by a legal officer from the Thirteenth Air Force. (Even though the 355th Wing was under the operational command of General William Momyer of the Seventh Air Force in Saigon, all administrative and legal matters came under the Thirteenth Air Force.) The indictment listed the charges as destruction of government property (the gun camera film) and conspiracy to deceive authority. Under Article 81 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the three officers could be dismissed from the service, with forfeiture of all pay and allowances, and face up to 12 years in prison.

Artist Adam Tooby

captures the sense of what it was like to attack North Vietnamese targets in

an F-105 Thud, an experience that Broughton, Tolman and Ferguson knew well.

The court-martial took place in October 1967 at the headquarters of the Thirteenth Air Force at Clark Field near the Philippine capital of Manila. The president of the court was Colonel Charles “Chuck” Yeager, the combat pilot who had achieved fame as the first person to break the sound barrier. He took the position after other officers had bowed out, knowing that if they issued lenient sentences, it could prove detrimental to their careers. “Jack was a helluva commander and a great combat pilot,” wrote Yeager. “Nobody was proud of his cover up, but I didn’t think he should be made the Air Force’s whipping boy.” Yeager sympathized with Broughton and his pilots and was determined to see that they got a fair trial, even though he knew the Air Force brass wanted to make an example of them.

Tolman and Ferguson were acquitted due to the lack of evidence, in particular the lack of gun camera footage. The court also dropped the conspiracy charge but found Broughton guilty of the lesser charge of destroying government property. It was the best compromise Yeager could arrange. He had conferred with the other officers on the court, and they agreed to follow this suggestion. Broughton was fined $100 per month for six months, the assumed value of the destroyed film.

Even though Broughton had avoided prison, the incident derailed his career. Yeager said later that the punishment “was a kiss of death because the only way for a senior officer to survive a scandal of that magnitude was to have all charges against him dismissed. He would never again have a command.”

An officer who had attended the court-martial told Broughton that one member of the board later said, off the record, that the entire affair was the “grossest miscarriages of military justice.” _ _

Colonel Harry C. Aderholt of the 56th Air Commando Wing, who also served on the court, said it was “the most disgusting episode of my life.” Ken Bell, who had flown missions with Broughton, was equally demoralized by the situation. “Three pilots who had risked their lives for their country had been whisked away and hung out to dry in an uphill fight for their honor and professional future,” he wrote. “I felt betrayed.”

A fellow pilot said Broughton

“exuded confidence, with just a trace of danger.” Broughton had hoped to

finish his time in Vietnam with 105 missions in the F-105, but fallout from

the Turkestan ended his combat flying. Instead he detailed his experiences in

books like Thud Ridge and Going Downtown. In the latter book Broughton

detailed his frustrations over the Turkestan incident.

On October 15, 1967, an article appeared in the Miami Herald , in which an unnamed but apparently reliable witness in Hong Kong stated that he had been aboard the Turkestan after the incident, and he had seen bullet holes in the bridge plating. He said the bullets had entered the metal at a horizontal angle, not from an elevated one that would have indicated an attack from an aircraft. The holes were made by 15mm and 40mm shells, he said, not American 20mm.The clear implication was that the North Vietnamese gunners, trying to hit the Thuds, had raked the Soviet ship by accident. But this revelation came too late to help Broughton.

Ryan, infuriated by the light sentence, ordered Broughton out of Vietnam. He was assigned to the Pentagon, where he began work on his memoirs, a scathing indictment of the air war that he titled Thud Ridge. He also worked with a lawyer on his appeal. In July 1968, the court findings were set aside in light of Broughton’s superb record. His status in the Air Force was at last cleared of all censure, but the entire affair left a bad taste in his mouth and he retired from the Air Force that August. “I found it interesting that in the entire history of the United States flying forces, only one other officer had ever had a general court-martial set aside and voided,” Broughton wrote. “His name was Billy Mitchell.”

Tolman and Ferguson were allowed to keep flying. Ferguson ended up with 103 combat missions and experienced a steady climb in the Air Force, retiring as a brigadier general in 1982. He died in 2007. Tolman also continued flying combat missions and retired as a colonel. Now 91, he lives in his native state of Maine.

Broughton wrote two other books, Going Downtown: The War against Hanoi and Washington (1988)and Rupert Red Two: A Fighter Pilot’s Life from Thunderbolts to Thunderchiefs (2008). Both are recommended reading for anyone interested in the air war over Vietnam. The holder of two Silver Stars, four Distinguished Flying Crosses and the Air Force Cross—the flying arm’s highest award—and one of the most respected officers who served in Korea and Vietnam, Broughton died in 2014 at the age of 89.