The Oral History of Billy the Kid

Recommended for you

With smoking six-guns Billy the Kid blazed a path across American folklore as wide as the Chisholm Trail. Fact and fiction meld inscrutably in the tales of the young desperado in a tradition rumored to have been started by Billy himself when he claimed to have gunned down 21 men, “One for every year of my life.”

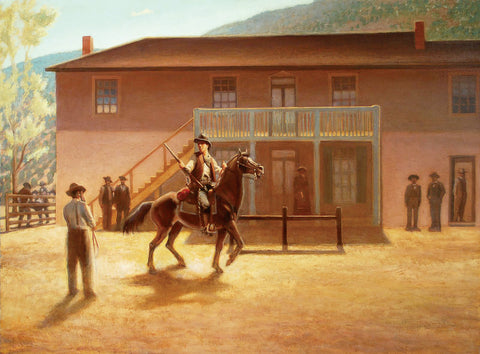

Countless books, articles and big- and small-screen productions have made the highlights of his brief life common knowledge to even the most passive Western aficionado. Young Billy first broke jail in Silver City, New Mexico Territory, in September 1875, killed a reputed bully in Arizona Territory in August 1877, then returned to his adoptive territory. By that November he was riding for English businessman/rancher John Tunstall in turbulent Lincoln County. When Tunstall was shot down in February 1878, the Kid and the other self-proclaimed Regulators sought revenge against his killers, setting off the Lincoln County War. Things heated up on April 1 when Regulators gunned down the county’s corrupt sheriff, William Brady, then boiled over in July amid a five-day fight between the competing factions that culminated with the burning of the McSween house and killing of businessman Alexander McSween. After the war the fugitive Kid, who had supported McSween, elected to remain in the county. That unwise decision led to Billy’s capture at Stinking Springs in December 1880, followed by a busy April 1881 marked by the Kid’s conviction for Brady’s murder at trial in Mesilla and his bold escape from the Lincoln County Courthouse, during which he killed two of Sheriff Pat Garrett’s deputies. Swearing never to be caught alive again, the Kid got his wish when shot down by the relentless Garrett on July 14, 1881, in friend Pete Maxwell’s bedroom at the latter’s family ranch in Fort Sumner.

Stories of the Kid’s romances have also made the rounds. Paulita Maxwell, a daughter of prominent rancher Lucien Bonaparte Maxwell and sister to Pete, was popularly believed to have been one of Billy’s lovers. Some even allege she was pregnant with Billy’s baby at the time Garrett gunned down the fugitive Kid in her older brother’s bedroom. Another rumored lover of the man known as William Bonney was Sallie Lucy Chisum, a niece of cattle baron John Chisum, although it is far more likely they were just friends.

But other stories rarely make it into the history books, tales of horse races, knife play, poker games and dances. Though less dramatic than such events as the public shooting of Sheriff Brady or the ambush killing of Deputy Bob Olinger from a second-story window of the Lincoln County Courthouse or Billy’s alleged romances with Paulita and Sallie, such anecdotes paint a more complete picture of the daring youth who captured the imagination of so many American readers.

One of the Kid’s reputed lovers was Paulita Maxwell, and

Joe Ciccarone depicts them as a couple in his black-and-white portrait Billy

the Kid and Paulita.

As part of the federal Works Projects Administration (WPA), which between 1935 and ’43 put some 8.5 million people to work to alleviate unemployment amid the Great Depression, the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) sent hundreds of writers nationwide to record the life stories of a broad swath of Americans. The resulting documents offer a unique glimpse into the past, recording diverse facets of interviewees’ lives, from their occupations and religious practices to their political views and even their favorite meals. Amid the fascinating tales of those who settled the West, alongside thrilling accounts of Indian raids and cattle rustling, is the occasional offhand reference to Billy the Kid.

Not all such recollections should be accepted at face value, of course. “One of the perils of a Kid/Lincoln County War historian,” explains one such historian, James Mills, “is having to differentiate between the realistic recollection of old-timers and where they got a little carried away or their memory muddled in some cases.”

Case in point is a tale told by Francisco Gomez, who was 83 years old when interviewed in 1938. Gomez had worked for the McSweens and claimed to have ridden with the Kid against a pair of rowdies who shot up Lincoln. “[Civil War veteran] Captain [Saturnino] Baca was sheriff then,” Gomez said, “and some tough outlaws came to Lincoln and rode up and down the streets and shot out window lights in the houses and terrorized people.” At Baca’s request, the old-timer alleged, Billy led Gomez, José Chavez y Chavez and two other men on a hunt for the badmen. “The outlaws went to the upper Ruidoso, and we followed them. We caught up with them and shot it out with them. One of the outlaws was killed, and the other ran away. None of us were hurt.”

In the 1930s Elbert Croslin, who was born four

years after Billy was slain, related a story in which he was in Portales, New

Mexico Territory, and nearly crossed guns with a poker player a hotel

proprietor warned him was the notorious Kid.

In all fairness, decades had passed between the time of the alleged events and when Gomez related his story. As historian Mills notes, however, Baca had finished his term as sheriff before Billy ever arrived in Lincoln County. “The incident may well have occurred while Baca was sheriff, but Billy wouldn’t have been involved,” Mills said.

So, was Gomez mistaken about the Kid’s involvement or wrong about who was sheriff at the time? Either seems feasible. But Gomez had other clear recollections of Billy. “He used to practice target shooting a lot,” the old- timer recounted. “He would throw up a can and would twirl his six-gun on his finger, and he could hit the can six times before it hit the ground.”

Interviewed by the FWP at age 82 in 1937, Annie E. Lesnett was married to a local storekeeper and hotelier and was the mother of two young children at the time of the Lincoln County War. Acquainted with Billy, she corroborated his skill with firearms. “The Kid was one of the quickest, most accurate shots in the Southwest,” she recalled. “He often said, however, that he wished he were as accurate with a six-gun as he was with a rifle. He was good with a pistol but excellent with a rifle.”

According to Jack Robert Grigsby, who was born in Tyler, Texas, in 1854, orphaned as a boy and moved to Lincoln County when he was 16, Billy was just as adept with a knife. In a cattle camp near Hackberry, Texas, Grigsby looked on as the Kid got into a fight with a fellow hand that quickly turned violent. “Billy cut the Negro across the side of the face and down the back with a long butcher knife,” Grigsby recalled. The victim fled, then collapsed. As the wounded man pleaded for his life, the Kid snapped, “Oh, shut your damn mouth! I have already done all to you that I want to.” Billy’s reaction, as reported by Grigsby, coincides with other accounts of the Kid’s cool detachment. “Billy stood there and wiped the blood off of the knife with his hands…as unconcerned as if he hadn’t done a thing. But he left after that. He was afraid the officers would hear of this and would get him for other things he was wanted for.”

The Kid certainly had a fearsome reputation. George Bede, who arrived in New Mexico Territory in 1877 and worked on Chisum’s Jinglebob Ranch near Roswell for five years, had regular interactions with Billy. “Whenever I met him, he acted mighty decent,” Bede recalled, “and ’twas generally said about him that he never turned a fellow down that was up against it and called for a little help. But, also, the folks ’lowed he would shoot a man just to see the fellow give the dying kick. ’Twas said he got a powerful lot of amusement out of watching a fellow that he didn’t like twist and groan.”

Apocryphal or not, such tales stood the Kid in good stead at times. Take, for example, an anecdote from Ambrosio Chavez, whose cousin Martín was a friend of Billy’s. Chavez recalled a prize match between Martín’s mare and a fast horse owned by a group of passing Texans. The bet was three fat beeves. But when Martín’s mare won the race by a wide margin, the Texans cried foul and angrily refused to honor the wager. Shortly thereafter the Kid arrived at Martín’s for a visit, and on hearing the story, he determined to visit the Texans and set the matter straight. “The women at Martín’s ranch just begged Billy not to go to collect the bet,” Chavez said, “as they were afraid that there would be trouble over it, and that Billy might get killed. But Billy just laughed at them.” Armed with two pistols and two cartridge belts, the Kid rode into the Texans’ cattle herd and shot down three of their best animals. He then told Martín to have the Texans deliver the meat. “The Texans were so scared when they found out that he was Billy the Kid that they broke camp and left right away.”

Another tale that cast the Kid in a heroic light came from Pedro M. Rodriguez, who was born in Lincoln County in 1874. His 1938 interview centers on Indian fighting, specifically his father’s service in then Captain (and future Lincoln County sheriff) William Brady’s 1st Regiment New Mexico Volunteer Calvary, headquartered at Fort Stanton. “In those days,” Rodriguez said, “the Indians roamed all over Lincoln County and were always killing people and stealing cattle and horses.” When Indians threatened the family cattle herd, Pedro’s grandfather gathered a posse of cowboys, the Kid among them, to ride into Turkey Canyon and drive the cattle down to the Ruidoso. Halfway up the canyon some two dozen Mescalero Apaches, led by Chief Kamisa, intercepted the wranglers. Amid a parley the Indians subtly moved in to surround the cowboys. Keeping a cool head, the Kid instructed his fellow hands in Spanish to tighten up their horses’ cinches and follow him. “Billy mounted his horse, with a six- gun in each hand, and started hollering and shooting as he rode toward the Indians. The rest of the men followed, shooting as they went. They broke through the line of Indians, and not a one of the men were hurt.” The cowboys then rounded up the cattle and returned them to Rodriguez’s corral. “The next morning Kamisa and a band of Indians came to my grandfather’s house.” A deal was struck, and for the paltry price of three beeves the Apaches vowed to leave Rodriguez’s herd alone. “The Indians kept their promise and never stole any more cattle.”

For every story that paints Billy as a steely gunman, just as many describe an amiable young man many called friend. Gomez remembered the Kid’s big roan horse. “Billy would go to the gate and whistle, and the horse would come up to the gate to him. That horse would follow Billy and mind him like a dog.” Lesnett also had benign recollections of the Kid. “He was very fond of children,” she said. “He called my little boy [Irvin] ‘Pardie’ and always wanted to hold the baby [Jennie Mae].…He also had a little dog…[that] would jump up on the Kid until he would laughingly pull his gun and begin firing into the ground. The dog would playfully follow every puff of dust, yelping joyfully.” Billy also frequented local dances. According to Ella ( née Bolton) Davidson, who shared a memorable spin around the floor with the Kid, many a local hostess believed “the Kid had been led into evil paths and, through kindness and friendliness of hospitality, might be led back into the straight and narrow way.”

Pat Garrett

Many people spoke of the polite young outlaw with overt fondness. Berta ( née Ballard) Manning was 10 years old in 1879 when she settled with her family in Fort Sumner. “Yes, I remember Billy the Kid real well,” she recalled. “He was not rough looking and was very quiet and friendly. I never saw anything ugly about him or in his manners.…He was kind and could be a good friend. But I am sure we should not make a hero of Billy, for after all he was a bandit and a killer.” Berta’s brother, Charles Ballard, had a similar impression of the Kid. “I remember good times I had with Billy the Kid,” he recalled. “He was not an outlaw in manners—was quiet but good company, always doing something interesting. That was why he had so many friends. We often raced horses together.” Charles also touched on the Kid’s reputation as an outlaw. “Billy was credited with more killings than he ever did. However, there were plenty that could be counted against him. It was reported he was the one who killed [McSween attorney Huston] Chapman when Chapman refused to dance when ordered, but Billy had nothing at all to do with that shooting.”

Recollections of the Kid in the FWP in terviews paint a picture of a young man seemingly caught up in circumstances beyond his control. But however congenial a friend he may have been, he was indisputably an outlaw. J.H. “Jake” Byler spent his adult life punching cows and shared hair-raising tales about stampedes, gunfights and cattle rustling. “I ran cattle all over west Texas, from Tom Green to the Pecos and from there to New Mexico,” he recalled. While working as a hand for Tularosa Basin rancher Pat Coghlan, who had a government contract to furnish beef to reservation Indians, Byler learned not to question where the cattle came from. “A new hand knew better than to ask questions,” he said. “If he had any sense at all, he kept his mouth shut and stuck to duty. If he didn’t, he didn’t last long.

“Billy the Kid was doing his part of the stealing [of cattle] on the Pecos and selling to Coghlan,” Byler said. “I’ve slept many a night right by Billy and never asked a question, just got up next morning and took the cattle he had brought in up to the reservation without a word.” But rustling wasn’t the Kid’s only source of illicit income. According to Byler, Billy worked a side deal with local stage drivers. At a prearranged point the Kid would meet a stage, take the driver’s gun, make off with the strongbox and then split the take with the driver. To thwart the young outlaw’s depredations, the stage company outfitted one Sam Perry with fast horses and his pick of possemen and set him off in pursuit of the Kid. “Sam was a crook too,” Byler asserted. “He came by where Tress Underwood and I were working and tried to get us to go with him. He said Billy the Kid’s hideout was on the border, that he knew where it was, and that we could sell out to him and split, then get us an old pack jack, trudge back and tell that the Kid and his gang overpowered us and took everything we had.” Byler and Underwood declined the offer, but some weeks later Perry returned “just as he had planned, leading the old jack and loaded down with money. He took us into Silver City, and we all got drunk.”

Obviously, the Kid was not the only rustler to ride the range. Rumor had it even Garrett had ridden and rustled beeves with Billy. “Pat had been a partner of Bill’s before Pat went to farming and ranching,” Bede claimed. “Under some sort of an arrangement Pat surrendered and was not sent to prison.” Bede lived for a time on Garrett’s ranch and claimed the Kid came by frequently at the rancher’s invitation. “When Pat became a lawman, he sent for Billy.” According to Bede, who “heard some of the chinning,” Garrett tried to persuade the Kid to give up his desperado lifestyle, but Billy would have none of it. “I guess the Kid hankered for his amusement of watching shot men kick and groan.” In support of his allegation, Bede offered another anecdote:

I am sure father and I heard the last words the two men said on the subject of the Kid’s surrender.…The Kid was mounted and ready to leave, and Pat said to him, “Billy, you can see it my way, I guess?”

“No, Pat,” the Kid said.

“Well, you understand I have to either resign or kill you, and I am not going to resign.”

“You mean that you’ll try to kill me’, the Kid answered while laughing; and then he rode off, saying, “So long, pardner.” It was some spell after that last call of the Kid’s when Pat killed the fellow.

Not all old-timers, though, accepted the fact of the legendary outlaw’s death. “There seems to be evidence that Billy the Kid was not killed by Garrett but that he lived to be an old man down near Marfa, Texas,” said Dr. John Randolph Carver, who was interviewed in Fort Sumner at age 67 in 1937. Carver cited three reasons so many people refused to believe the Kid had died that night in Maxwell’s bedroom. “One is that his sister came out to see him and then did not go to his grave but went directly east. That his horse was never seen again is another reason. Third is that Pete Maxwell and Pat Garrett were his friends, and that a Mexican was buried instead of Billy the Kid.”

As with Elvis, Amelia Earhart and others, tales of the Kid’s survival and rumored sightings abound. Take a story told by Elbert Croslin, who made a living as a rodeo performer and claimed to have run afoul of Billy during a poker game. For the record, Croslin was born in 1885, four years after Garrett killed the Kid.

Croslin’s undated interview centered on bronco-busting and other wild adventures out West. He related one particularly punishing series of rides in Bonham, Texas. “I took so many falls that it hurt my pride quite a bit,” he said. “I didn’t even want to stay around, so I caught some freight trains and went to New Mexico.” While in Portales the broke, recovering rider found himself spectating at a poker game, drawn to it by the pistols and heaps of gold coins stacked on the table before each player. “I’d seen money like that in banks before,” Croslin recalled, “but not out in public.” He proceeded to “sweat the game,” skulking along the fringes to study poker hands and learn each player’s style. When one of the men made a foolish play, Croslin grunted in derision. Bad move. “He jumped around so quick that I never realized he was moving till he was facing me, and, Lawd! Lawd! he had his six-shooter pointed at my biscuits.” Noting Croslin was a mere lad, the player grabbed him by the shirt collar, dumped him outside on the boardwalk and returned to the game without uttering a word.

Journalist and writer Henry Alsberg (1881–1970) was

founding director of this New Deal program that employed some 10,000 out-of-

work Americans during the Great Depression. Its writers, including those above

from New York, interviewed people of all stripes, including some who claimed

to have known Billy the Kid.

Angered and humiliated, Croslin decided to seek revenge. “I thought I was some pumpkins, and I also thought that since they didn’t know me, I could get away with tough stuff, and they’d just think I was sure tough.…I finally made up my mind to get [my] pistol and go kill the man.” As Croslin returned to the hotel lobby with gun drawn, the white-faced proprietor snatched the gun from his hand. “You wouldn’t have a chance with that man,” he explained. “Why, he’s Billy the Kid, one of the best and fastest pistol toters the world has ever seen.” Sobered by the warning, Croslin left his six-gun behind and caught the first homeward-bound freight train. Further down in his interview he mentions having later joined a party of drovers trailing a herd past Stinking Springs, a known hangout of the Kid. “I took it up for another chance to see Billy,” he said. “I was disappointed, though, because a fellow named of Pat Carret [ sic ] had already killed him somewhere. I think that’s the way it was. Anyway, I never saw him.”

“After I got back home,” he recalled, “I had quite a few tales to tell about the cowpunchers, and did I tell about Billy the Kid. Of course, it goes without saying that I never told what really happened between him and me. The tale I told had a different ending!”

One may assume Croslin was simply relating a tall tale to his interviewer. “I always was kind of a hand to brag on anything,” he admitted. It’s likely the well-meaning barkeep simply told the cowhand his intended “victim” was Billy the Kid to spare the youngster trouble. Still, it appears Croslin believed the claim, or he wouldn’t have joined a cattle drive past one of the Kid’s hangouts. Or, perhaps in the same way present generations still idolize Elvis, folks who grew up in Billy’s shadow may have earnestly believed the Kid still roamed the West. Either way, stories like Croslin’s undoubtedly fueled the popular notion Billy had survived and may ultimately explain why so many people embraced the claims of such impostors as “Brushy Bill” Roberts, who insisted he was the Kid right up until his death on Dec. 27, 1950.

While the credibility of Billy the Kid encounters in many of the FWP interviews remains in question, that doesn’t make them any less interesting or entertaining. Aside from tales about the Kid, the interviews contain plenty to hold one’s interest. Charles Ballard, for instance, served as a Rough Rider during the Spanish-American War and rode in the honor guard amid Theodore Roosevelt’s second inaugural parade in 1905. In his interview Byler held forth on Indian raids, knife fights and barroom brawls around the poker table. His story of Billy the cattle thief and stage robber was but one anecdote from his own long life of adventure.

Whether or not we believe such tales of the legendary Billy the Kid, the FWP interviews in the archives of the Library of Congress represent a valuable collection of American folklore and Western heritage. While they may not stand up to historical scrutiny, they sound mighty fine when shared around a campfire.

Mark Iacampo, who once performed stunts as a Rough Rider at the Rawhide Western Town in Scottsdale, Ariz., is a freelance writer for publications on three continents. For further reading he recommends Billy the Kid: The Endless Ride , by Michael Wallis; The Real Billy the Kid , by Miguel Antonio Otero Jr.; and the Library of Congress collection American Life Histories: Manuscripts From the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936 to 1940, searchable online atloc.gov/collections/federal-writers- project.