The Great Stewardess Rebellion With Nell McShane

Girdle checks. Public weigh-ins. Automatic termination at age 32. Such were the conditions experienced by many female flight attendants in the not-so-friendly skies of the 1960s and 1970s, as journalist Nell McShane Wulfhart makes clear in this compelling account. Far from living the chic image of international jet-setters, American flight attendants—numbering more than 20,000 by 1967—worked punishing schedules, earned wages often lower than those of cleaning crews, were portrayed as sex objects rather than crucial safety professionals, and lost their jobs if they gained weight, became pregnant or married. Wulfhart illustrates her points with some contemporary advertisements in the book, including Braniff International’s 1965 “Air Strip” campaign, which had flight attendants remove articles of clothing throughout each flight. Thwarted in their efforts for more just treatment from their union and airline management, flight attendants enlisted prominent feminists such as Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan for support, undertook efforts at organization and publicity and turned to the fledgling Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for legal action under Title VII of 1964’s Civil Rights Act, although the EEOC tended to prioritize race rather than sex discrimination. Legal cases—including those of men, who had been mostly shut out of the flight attendant profession—resonated beyond the airline industry and established important precedents for equity in the workplace.

Wulfhart follows a few key players in this fight. Among them are feisty flight attendant Patt Gibbs, who later became a pilot and union president; diplomatic flight attendant Tommie Hutto-Blake, who also served as a union president; flight attendant Brian Hagerty, who faced homophobia; and flight attendant Cheryl Stewart, who encountered strange questions such as “How does it feel to be colored?” Their inspiring tales of grit and guts illuminate a dark space in aviation. —Elizabeth Foxwell

AN INTERVIEW WITH NELL MCSHANE WULFHART

(Transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.)

Before I do that, though, I’m going to give you a little plug for the magazine in case you have never heard of it before. If that’s the case, shame on you. We are Aviation History, we cover all aspects of the heritage of flight—balloons, jets, propellers, military, civil and commercial. And obviously, today we’ll be looking a little bit at the commercial aspect of aviation.

The Great Stewardess Rebellion

by Nell McShane Wulfhart, Doubleday Publishing, April 2022, $24.75

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

You can read a treasure trove of material from the nine magazines in our history group—everything from the wild west to the Civil War to World War II. And you can also subscribe to the magazine on the website there. So, I encourage you to do that.

And now without further ado, let’s go back and begin the interview with Nell McShane Wulfhart and The Great Stewardess Rebellion.

There were places in the book where I just had to put it down and shake my head in disbelief. the blatant sexism that would seem unrealistic if it were even on an episode Mad Men, but this was real life and it really happened. What was it that prompted you to write this book?

Well, I think every journalist spends a lot of their time thinking about book ideas. We’re always looking for the great idea, and I kind of processed a lot of them. And when I stumbled upon this one, it was actually during an interview with Adam Conover. He has sort of a TV show where he does myth busting, and he was describing to me that when we think about the golden age of travel, we think about Mad Men, we think about Don Draper or cocktails in first class you know, roast beef, this extremely luxurious experience. But how the flip side of that was that for the women working the cabin, the stewardesses, it was the most sexist workplace in America. The working conditions were terrible. And he was telling me about this. And I was like, that sounds like it would make a great book. And then I sort of ran off and wrote it.

Tell me a little bit about some of the indignities, that flight attendants, or stewardesses as they call them back then, had to face during this “golden age” of air travel?

Well, there are many and even to get the job, you had to meet a very long list of criteria. It had to be—you had to have very straight teeth, for example. You couldn’t wear glasses. You had to be a certain height, and you had to be a certain weight. The airlines all had extremely strict weight restrictions that were determined according to height. So, all the women on the plane were very slim, and at least at the beginning of the sixties, it was a given that you had to be white. So, if you managed to jump through all those hoops and pass that test, once you got on the plane, then you had to…well, you had to wear girdle at all times. You had to maintain that weight because any manager or pilot could pull you onto a scale at any point and if you were a few pounds over your weight, you could be taken off the flight. And then there was the limit of your tenure because if you got married, you were fired, if you got pregnant, you were fired. And if you manage to avoid both of those things, when you turned 32 you would be fired.

What came first, did you start researching the book and then find these people, or did you find these people and then start researching the book?

Those two things happened at the same time. The two main characters in my book—I also sort of think of them that way, although they’re real people and they’re still alive and I talk to them all the time—the two women I focus on, Patt Gibbs and Tommy Hutto-Blake, they sort of spearheaded this worker’s rebellion, this revolution in the air, and so their story is really bound up in the whole story of the stewardesses and how they managed to change their workplace. And it’s kind of like a personal transformation that happens along with a workplace transformation, with a professional transformation.

At what point did you specifically seek out these people? As you did your research you said oh, this is a very important person for the story I’m telling so I need to get in touch with her.

Well, that’s exactly what happened. Like those names came to the top almost immediately in my research and then it turns out when you’re researching a book on stewardesses in the sixties and seventies that almost everybody you know knows a woman who was a stewardess in the sixties and seventies. It was a really popular job. I mean, it was a very exclusive, aspirational job. The airlines sold it as incredibly glamorous, travel the world, be free, be independent. So, it was very hard to get that job. But this really was the age at which air commercial air travel, as I’m sure your readers know, was really ramping up and so they needed a lot of stewardesses. And in the sixties, when you were a woman looking for a job, you could be a nurse, you could be a teacher, you could be a man’s secretary, but those were kind of your options and so stewardess—if you were a little more independent, or you wanted to get out of your hometown—stewardess really was a dream job for that.

It was also looked on in society at large as a kind of a placeholder job. It was fun. It was glamorous, it was a little frivolous and certainly not anything that any would consider a career.

Absolutely. I mean, I think the average tenure of a stewardess in the sixties was less than three years. I mean, most of them got married and they couldn’t keep their jobs after they got married. So, like, they were gone. And those particular restrictions, the marriage, the pregnancy, the age rules, they sort of had the double effect of not only keeping the workforce, very, very young and conventionally attractive, which was a way that they brought in customers, but it also had the effect on those women themselves because, it’s not really worth your while to start fighting for things like benefits or pensions or pay raises when you only expect to be on the job for a couple of years.

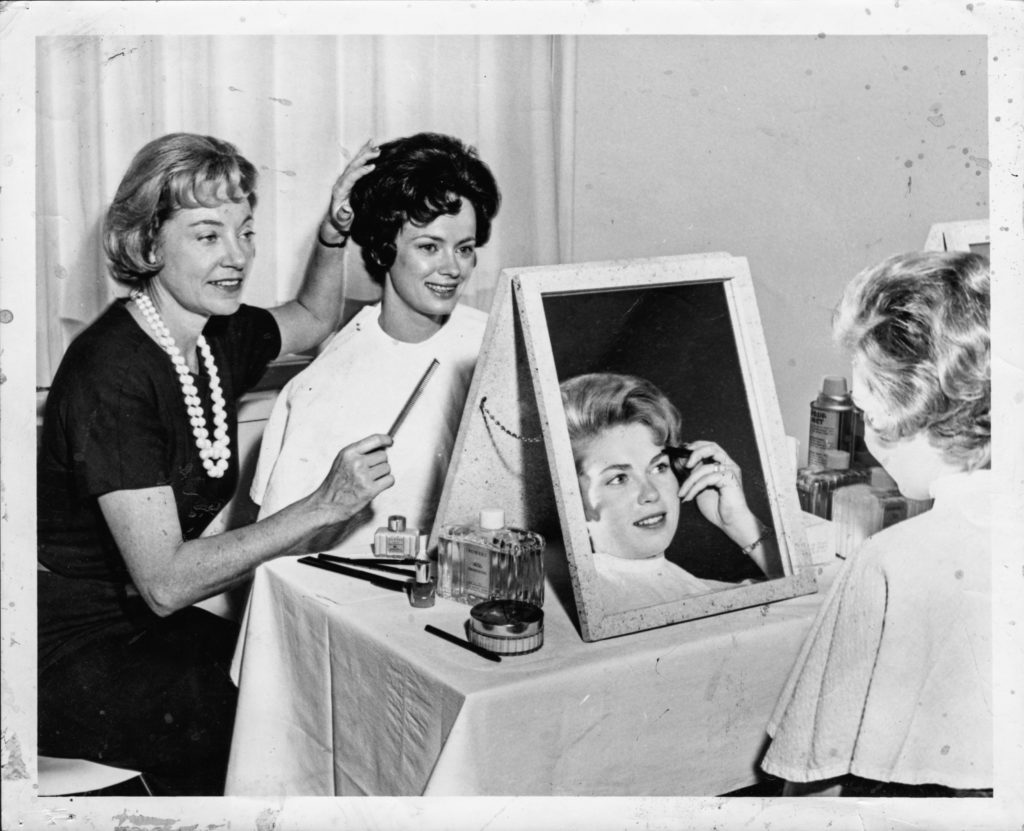

Can you tell me a little bit about this photo? This is one of your principal people in this shot, I believe.

Yeah. On the right-hand side of the photo, in the mirror, that’s Patt Gibbs. She’s my main character, really, I would say, and this is a photo of her at stewardess school in 1961. So American Airlines opened up this huge campus just to train stewardesses. And when you were hired for the job, when you’d passed all the weight requirements and made sure you didn’t have any unsightly scars or acne, you ended up at the stewardess college, which was colloquially known as the “charm farm.” And you spent six weeks on the charm farm living in a dorm, eating at a cafeteria and being trained to be a stewardess. And some of the time was about emergency evacuations and safety procedures. But most of the time was about styling your hair in the right way, using the appropriate company-sponsored makeup and having your nails polished exactly the right way. It was mostly about appearance. And after you spent six weeks on the charm farm, you’d be sent off to your base.

I recall an incident in the book where a flight attendant spilled coffee on her uniform and did not have a spare uniform and was therefore forced to wear a uniform with a coffee stain and was fired for that. Is that correct?

Yes. She was suspended for that, okay, without pay. Yes. And it was it was basically one of those restrictions. The uniform restrictions were incredible. Patt, the woman on the right in the photo, she incurred a disciplinary infraction at one point for not wearing her white gloves—gloves were part of the stewardess uniform—on an employee bus, because she was supposed to be wearing her entire uniform and went out in public, even though the only people around her were fellow American Airlines employees. So, all these restrictions, these are sort of the little incidents that start to spark this stewardess rebellion, because people like Patt started to realize that, you know, being suspended without pay because it was a turbulent flight and a passenger spilled coffee on your uniform, didn’t seem quite fair.

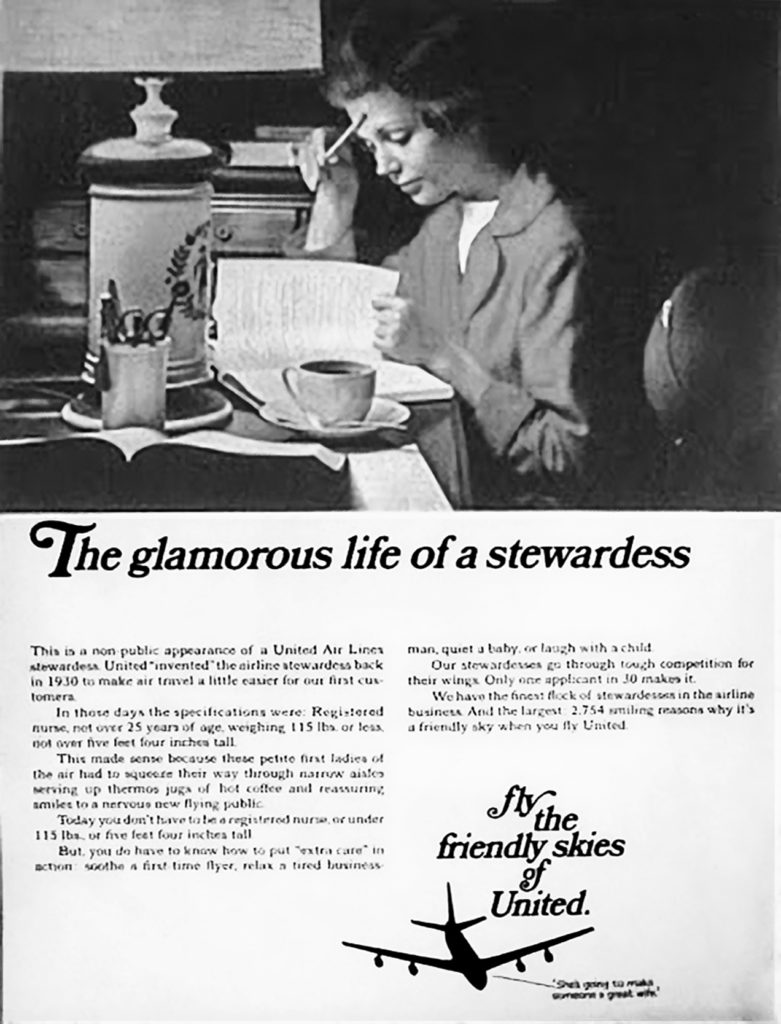

Let’s look at some of the advertising now. This one in a sense was better than the average because it does dispel the myth that it’s all glamour and that these women didn’t work very hard. On the bottom of this ad there’s a sort of word balloon coming out from the airplane that says she’s going to make someone a great wife. That pretty much sums it up. These weren’t “serious workers.” This was a placeholder job until they got married.

The airlines absolutely worked on the image of the stewardess as a wife in training. And they talked about this, even when they had hearings and they went to battle over the age rule and the marriage rule. They went so hard on the idea that they were training America’s wives, there were ad after ad that talk about oh, you’re going to meet a woman who can serve meals to 150 people at one time. I’m not sure how many women were really required to do that on a regular basis in the sixties or seventies, but it was a selling point that she was always smiling, always perfectly arranged from head to toe, not a hair out of place. And something that you’ll see in ad after ad—if you look in my book, there’s a lot more of these and some of them are really outrageous—but that they must always be smiling. That was an absolute job requirement.

And in fact, when the term “emotional labor” was coined, Arlie Hochschild was referring to stewardesses because smiling was absolutely like a job requirement. It was something you couldn’t get around. They had to look happy while they were working so hard.

Oh, absolutely. I think the most surprising and appalling ad in the book is, it was Braniff who did a thing called the “Braniff Air Strip” in which the stewardesses would remove an article of clothing throughout the flight. They didn’t get naked or anything but that was the implication, of course.

That was actually an ad that came out in 1965. And that was the first ad that really started what I would consider sort of a downward trend into really sexualizing the stewardesses. Before that a lot of the ads were kind of like the one that you can see in front of you, right? Now they’re talking about the hard work the stewardesses are doing, how they take care of their passengers. They’re almost considered like mothers on the plane, and then with the Braniff Air Strip, things really take a turn for the sexual and they posit stewardesses as like kind of like “sky bunnies.” I think was a term that they tossed around a lot. Yeah, some of these ads are really outrageous, but they get more degrading as the years go by.

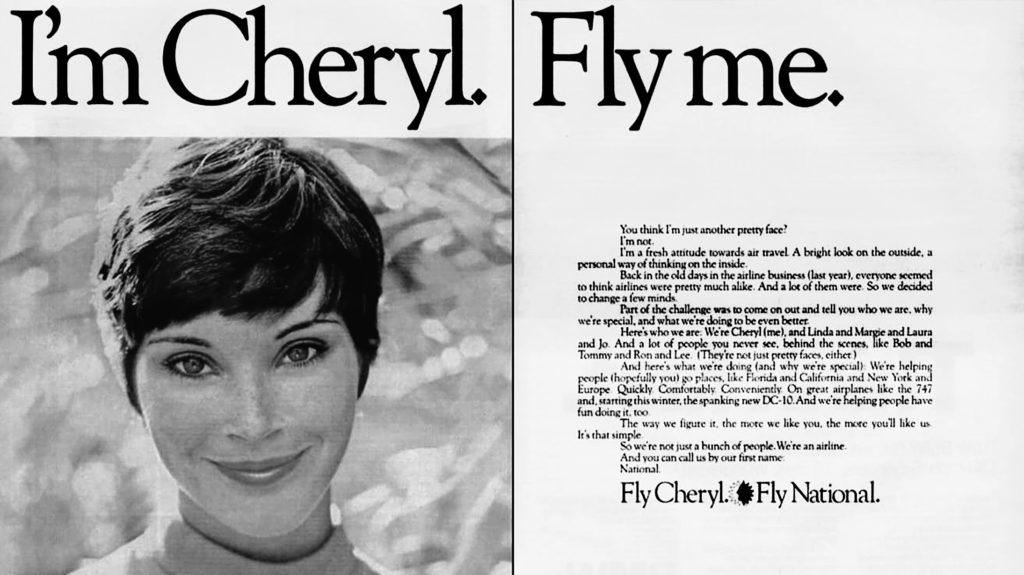

One of the most famous ad campaigns of all is the “Fly Me” ad, which you still hear people kind of refer to that in conversation. What airline was this?

This was National Airlines, which no longer exists. Like many airlines in my book.

I recall that some of the people in your book were a little ticked off about, not only this ad, but also the way people would treat them, saying, “Why don’t you fly me?”

That’s exactly right. So, this sort of double meaning of these ads—and these ads were everywhere, and they featured real stewardesses. So, the Cheryl that you’re looking at right now, Cheryl was a real working stewardess and they had “I’m Donna, fly me,” “I’m Karen, fly me.” They would even paint those names on the planes so you could watch Cheryl flying by in the sky.

So, the whole the whole “fly me” ad was something that really sparked a lot of anger in in the stewardesses. I mean, there had been incrementally worse and worse ads that were really sexualizing them and trivializing their work, sort of encouraging passengers to treat them as cocktail waitresses rather than safety professionals. And so ads like this were just making the problem worse. And this ad actually got them out on the streets picketing along with the National Organization for Women. They joined them, and they went and they picketed the ad agency in New York that had come up with this ad. And they had signs that said, “Go fly yourself,” which I thought was pretty clever. And this is another detail that I like. The owner of the ad agency, his name was Bill Free, he came out there and in a really spectacularly misguided gesture started handing out roses to the stewardesses who are out there picketing, sort of trying to placate them, and so they go home and they make new signs that say, “I’m Bill. Fire me.”

You don’t mess with the flight attendants.

As we’re learning every day.

They also had trouble with their own union. And I believe they split off and formed their own because they felt they weren’t being treated seriously. I think one of the sticking points was getting a single room between flights.

Yeah, I think this is a really interesting thing, just in terms of kind of all union negotiations. The things that the public thinks are the most important for a job, wages or benefits or whatever, are often not the things that the workers are really fighting for. So, the stewardesses were represented, most of them belong to the Transport Workers Union, which was, mostly subway workers, bus drivers, things like that. A lot of old men and they kind of treated the stewardesses like mascots of the labor movement. They didn’t really go to bat for them when it came time to negotiate with the airlines for the things that the stewardesses wanted. And one of the things that precipitate this sort of crisis in my book when the stewardesses leave the Transport Workers and they go to form their own independent women-led unions was the issue of single rooms on layovers, single hotel rooms.

So, when you’re flying and you have a layover, the airline puts you up in a hotel. And stewardesses had always shared rooms—there were always two to a room to save the airline money, but the pilots and the captains always got their own rooms. Okay, fine. And when there were only women on the plane, which was true for almost all the domestic airlines until the early seventies, okay, they could deal with it. Then once men started coming on board and, I think 1971, there was usually only one man working as a flight attendant on the flight and he always got his own room. So the whole crew would arrive, get off the plane, they’d get on the bus or the car, arrive at the hotel, and these women who had been working in the cabin cabin for maybe 10 years would have to share a room with each other while they’d see the man who had just come on board, just started flying, saunter off to his hotel room, with the key to his own solitary paradise.

So, so this was one of the issues that really sparked a huge revolution among the stewardesses, because the Transport Workers, when it came to negotiating a contract with American Airlines, refused to go to bat for this. They just thought it was not important. And so the stewardesses—this is a little spoiler alert—but they vote down the contract, two times, which is something that was unprecedented, they rejected the contract that the Transport Workers had negotiated for them because they said, “We’ve been telling you, single rooms, we need single rooms. This is a single rooms contract, this is it.” And there’s a lot of high stakes drama actually going around something that doesn’t seem that important to us as outsiders, but it was a huge workplace rights issue for them.

if you had a roommate who snored, then you would stay up and you’d be exhausted the next day and maybe spill coffee on your uniform.

And occasionally, not only would they have to share rooms with stewardesses that they knew, who had been on the same flight, but sometimes it would be a stewardess from another American Airlines flight and the airline would just make them bunk together. So, a total stranger. A lot of them were reading a book in the bathtub to avoid the light keeping the roommate awake.

And might seem like a small point, but it’s a question of respect.

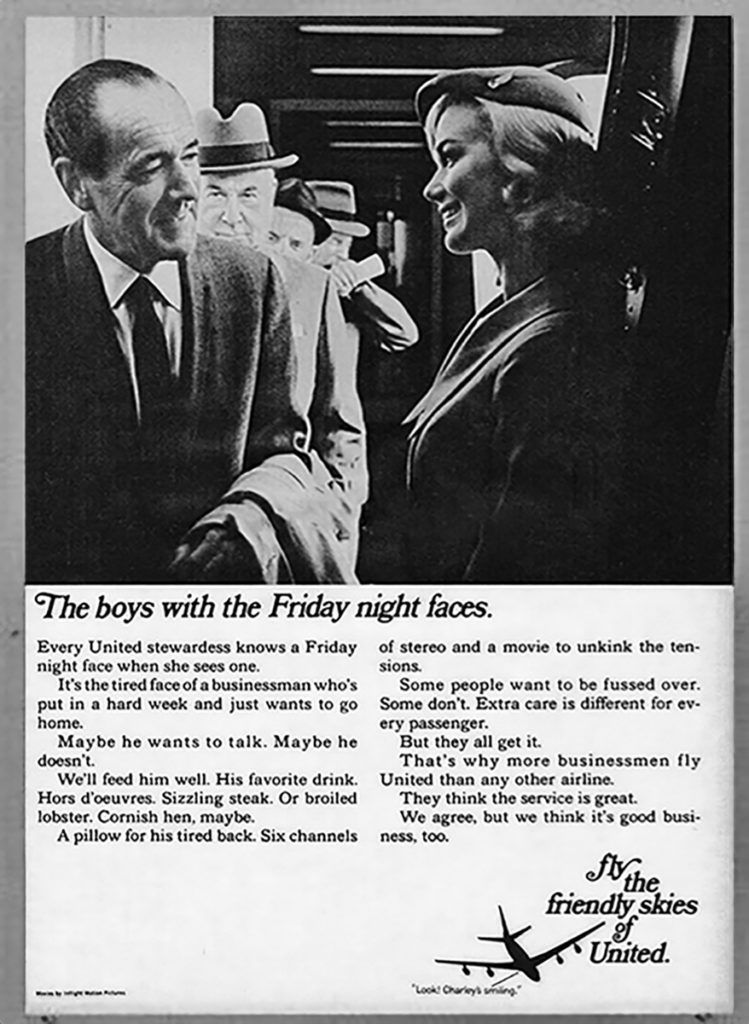

I have another ad here, “the boys with the Friday night faces.” First of all, those don’t look like boys to me, but this is the idea that these important, busy businessmen have to be fussed over and coddled by the stewardesses.

Businessmen, single male business travelers, everyone was scrambling to get this market share. And that’s probably still true today. But these are the most coveted passengers. This is one of the reasons that the airline ads get kind of racier and racier as the seventies go on because they’re really trying to attract these men and convince them to fly on their airline. And yes, a lot of it are ads like this where it’s like, a stewardess is there to attend to your every need. She’ll intuit whether you want to talk. If you want to talk, she’ll talk. You don’t want to talk, she’ll leave you alone, she’ll bring you the drink that you want. You’re going to be like, completely pampered by this young, very conventionally attractive woman, like that’s it. I will also add that the increasing sexualization of the stewardesses resulted in some extremely bizarre uniforms that the airlines put them into.

Yeah, I recall hot pants.

Yeah, Southwest had orange hot pants and white lace-up go-go boots and I just cannot even imagine the idea of serving hot coffee to a plane full of passengers wearing hot pants. But that’s just one of many. They get increasingly weird and increasingly tiny.

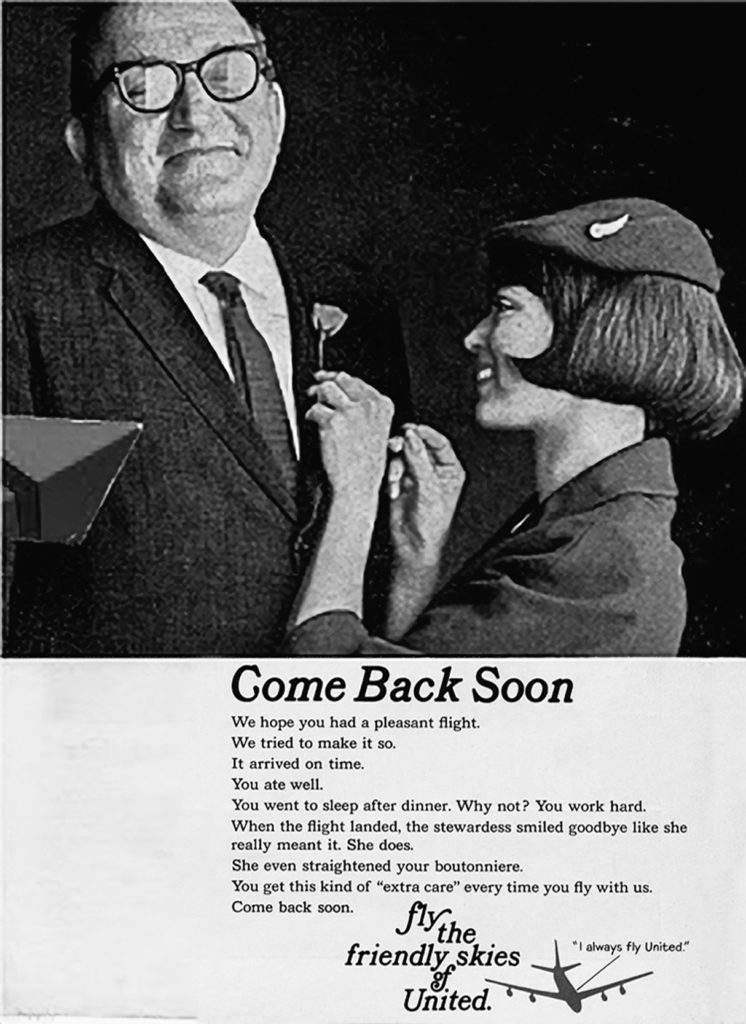

Oh, here’s another one, pampering the businessman passenger. It’s a bizarre ad, I have to say. Now, how does this all tie in with the rise of the feminist movement? it seemed like these were two converging streams that ended up kind of joining together at one point.

Yeah, I think as is as the seventies went on and the feminist movement really grew in power, there was this contrast between what the stewardesses were experiencing in their everyday life, sexual liberation, consciousness raising, being out without makeup or without bras, and long hair and just this incredible freedom that they were starting to feel in the seventies. And then, when they went to work, they had to put on their girdles and put on their, their tiny skirts, uniforms, and be talked down to by passengers and by pilots and by supervisors, really treated as girls. “Girls” was a word that the airlines used all the time to describe the stewardesses. They never refer to them as women, they all refer to them as girls. So, it was an increasing contrast between like what was happening outside on the streets, and just sort of time warp they entered whenever they like stepped onto the plane.

And you can even see behind me here, this is a group called Stewardesses for Women’s Rights, which was the group that protested the “fly me,” ad and they were a group of stewardesses who formed in 1972 in New York, and a group of feminists who were all working stewardesses from all different airlines. And their goal was to fight for better rights for themselves in the cabin. And Gloria Steinem was a huge supporter.

Which makes perfect sense. Obviously, they made big changes in their working conditions, and did make improvements. But now today you read about things that even seem a little more horrific, in which flight attendants are being assaulted on flights by out-of-control passengers. And you don’t go into that stuff in the book, but I’m just curious about your feelings about that. Have things gotten even worse in the skies?

That’s really good question, and I think it goes back to what you mentioned earlier, which is respect. There has just been a lack of respect for flight attendants since the sixties and seventies. Since the airlines went in so hard on this “Sky bunny” image, and that just hasn’t gone away. People still have that idea about flight attendants. And they also don’t really believe that flight attendants are there in case of an emergency or as safety professionals, you know, they really think they’re just here to bring me a tiny can of Coke or a biscuit or something. So, I think what we’ve seen, especially throughout the pandemic, with people rebelling against mask mandates or getting very drunk on the plane and assaulting flight attendant—there was that incident with Frontier Air where that drunk passenger was groping the female flight attendants, and then I think punched the male flight attendant, and then they had to duct tape him to his chair because there was nothing else to do.

Which is maybe an extreme example, but that sort of disrespect is happening all the time for flight attendants and because they’re relied upon by the airlines to not only be servers of food and safety professionals, but now also kind of security guards. So, there’s a lot of benefits to working as a flight attendant, but I think a lot of people have quit over the last few years because they just can’t handle the disrespect from the passengers.