The American Civil War Through the Eyes of the French

One of the great benefits of working in the field of Civil War history derives from the generosity of other scholars. Their sense of shared exploration promotes the circulation of materials that otherwise would remain unknown. More than 25 years ago, I met Donald E. Witt, a scholar of French literature with a deep interest in the American conflict. He had spent years translating the French newspaper Le Temps ( The Times ) for the period 1860-65. Because historians had frequently quoted the British press but paid relatively little attention to French newspapers, the materials he showed me seemed especially fresh. Happy to know someone else shared his enthusiasm for the project, he gave me seven thick binders containing more than 3,500 pages of translations.

A perusal of Le Temps revealed a rich body of descriptive and analytical evidence. The newspaper’s correspondents pursued an expansive approach to the American war that addressed politics, military affairs, swings of national morale, diplomatic maneuverings, and other topics. Political and military leaders figured prominently in the articles, which suggests Parisians exhibited a desire for such news.

Fourteen newspapers served Paris in 1861. Napoleon III’s government sponsored Moniteur and received largely favorable treatment from several other papers deemed “semi-official press.” Le Temps , which would become one of the important French dailies, supported the house of Orleans. With a pro-Union, antislavery editorial slant, it stood at odds with a pro-Confederate imperial press. In October 1861, Le Temps made a distinction regarding slavery’s role in the American crisis. “Yes, slavery is at the root of the war,” read the piece, “since it is the institution of slavery that, in the North and in the South, has made two nations, has created hostile interests between them …that has determined for her (the South) the rupture of the pact…” But it was not a war to kill slavery because “the abolitionist opinion has ever been, in the North, only that of an intimate minority.”

Le Temps allocated considerable attention to the Emancipation Proclamation. Noting that President Lincoln’s preliminary proclamation of September 22, 1862, finally “placed the debate between the North and the South on its true terrain,” the editors labeled it a military expedient forced on Lincoln by Rebel victories in the Eastern Theater. The paper found it “regrettable that the President hesitated for so long a time” and quoted from his letter to Horace Greeley dated August 22, 1862, concluding that “[t]his policy has only one aim, the re-establishment of the Union.” The newspaper responded to the final proclamation, which it termed “very important news from America,” on January 15, 1863. “This proclamation,” read the perceptive article, “…can hardly have any immediate effect; but it is not any less one of these utterances destined to have repercussions in history, to be converted into acts, and to become definitive.”

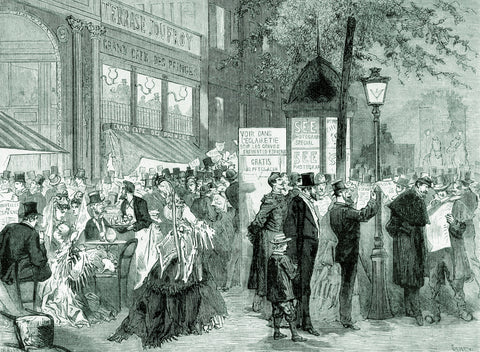

The January 15, 1863, edition of Le Temps discusses

the Battle of Murfreesboro, fought from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863,

as well as the Emancipation Proclamation.

The prospective dual between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee in 1864 generated sustained coverage in Le Temps that praised both commanders. “General Grant has acquired in his western campaigns habits of vigor” that would allow him “to lead the Army of the Potomac to victory,” while Lee, a general of “remarkable talent,” had won victories that showcased “the courage and energy of the Confederate troops.” Le Temps initially predicted Union triumph, largely because of faith in “the military capacity, but especially in the tenacity and the character of Grant.”

After the Battle of the Crater, the editors adopted a more ambivalent stance. “Whatever will be the denouement of this campaign in Virginia,” observed a piece treating Lee and Grant as equals, “it will remain a testimony of the indomitable tenacity of the two armies and the two generals who resist each other for so long…without any perceptible advantage on either side.”

Grinding operations in Virginia between early May and August 1864 set up a long piece in early September. Analyzing the two societies at war, a correspondent explored the combatants’ national morale and chances for victory. Confederates had faced “bankruptcy, despotism, famine” and “no longer have anything to hope for except independence; they no longer have anything to lose except their life.” The author admired “the courage that they deploy in this long resistance” and resoluteness in “this obstinacy of a common people who, for two years, block[ad]ed, invaded, decimated, found resources, [and] faced immense forces from the Union.” The Confederate economy lay in ruins “from top to bottom; all able men from fifteen to fifty-five are under arms….One no longer sees but women in the families and Negroes in the fields.” Yet Confederates manifested discipline born of “a unity of will” and still “held on, and no one can say when they will succumb.”

The United States presented a vastly different picture. It “has not renounced its richness,” asserted the author, “the war has interrupted neither its industry, nor its commerce.” Daily life progressed essentially as in peacetime, and Northerners shrank from “extreme measures, acting little and spending a lot, placing mercenaries opposite seasoned men, wasting immense resources without breaking down a poor enemy.”

The Union effort lacked the sense of collective direction evident in the Confederacy. Writing before the full impact of Sherman’s capture of Atlanta had become evident (travel across the Atlantic took 10 days or more), this writer perceived a possibly disastrous lack of will above the Potomac: “The North can yield to fatigue; then the war would have served only to substitute a national hate for a political rivalry; and to ruin more profoundly the Union.”

Four months later, on January 2, 1865, the paper had changed its tone. It celebrated the “re-election of Mr. Lincoln, and the manner in which it was accomplished” as “the gage of an indestructible liberty, and will remain in history as an imperishable testimony of political and moral grandeur.” The editors accurately predicted the difficult road that remained ahead: “[If] it is no longer hardly possible to doubt the re-establishment of the Union, the final success, and especially the final pacification do not appear still less a rather lengthy operation.”

Whenever I see the seven binders on the bookcase in my library, I think of Donald Witt’s great generosity and the trove of French evidence he made available to me.