Law and Some Disorder in the Wild West

Thousands of men enforced the law on the Western frontier as constables, sheriffs, policemen, marshals and detectives. Most of their work involved routine duties—e.g., collecting taxes, seeing licenses were up to date, arresting wife-beaters, keeping a lid on the illegal sale of booze, checking store doors at night and generally ensuring things were under control in the saloons, gambling sites and other entertainment spots. Gun duels, hangings and the pursuit of stage and train robbers were not nearly as frequent as Western films and TV series suggest.

Most lawmen were on the up-and-up. Virgil Earp, Bill Tilghman and Charlie Siringo met with extraordinary circumstances during their careers, each performing admirably in law enforcement positions across several Western states and territories. Other men proved dependable when wearing a badge but not so much as ordinary citizens. Virgil’s brother Wyatt, for example, was once arrested for riding off on someone else’s horse, pimped in Peoria, Ill., in 1872 and in 1911 was known to the Los Angeles Police Department for running an illegal faro game. In Cochise County, Arizona Territory, Burt Alvord put in good years as constable and deputy sheriff but tilted when he took up robbing trains.

Still others were just no good. Elected marshal of Nevada City, Calif., in 1856, Henry Plummer showed his true colors the following year. After arresting a wife-beater, he turned to comforting the aggrieved wife, often at night, and ultimately killed her husband. Though sentenced to a long term in San Quentin, Plummer was released in 1859 for “health” reasons and eventually landed in what soon became Montana Territory. In 1863 he convinced locals to elect him sheriff of Bannack, in the new gold strike region. In a matter of weeks the Plummer Gang, as writers dubbed it, committed scores of robberies and murders—exactly how many has been a subject of debate, especially in the last quarter-century. The gold-hungry Montanans of Bannack, Virginia City and other boomtowns ran out of patience with the road agents and other hard cases, and in January 1864 they went on a hanging spree. In the deadliest episode of vigilante justice in U.S. history, citizen mobs threw 20 men “necktie parties” by late January, the toll rising to 50 by October 1867. The most notable victim was Sheriff Plummer, whom vigilantes hanged from the Bannack gallows on Jan. 10, 1864, alongside Deputies Ned Ray and Buck Stinson. Certainly, that trio must have known crime and punishment go hand in hand.

The “no-good” definition certainly fit Thomas Kelly, a long-time clerk in the San Francisco City Police Department who was often hired as a special officer. He was also a pickpocket and carried weapons when not authorized. His long arrest record included several arrests while he was being paid as an officer of the law. He earned a place in Police Chief Isaiah Lees’ Rogues Gallery in 1899. The word in San Francisco was that Kelly was protected by his “Irishness,” no small thing in the law and order community of that era. In any case, Kelly proved nearly as two-faced, if not as notorious and unlucky, as Plummer.

Several of the lawmen who strayed had checkered pasts or fell on tough times. Billy Blankenship worked his way up from constable to deputy sheriff of Maricopa County in Arizona Territory and then city marshal of Phoenix in the 1880s. But the death of his daughter reportedly turned the marshal into a lush. As a result he fell short in his accounts, collected illegal taxes and was on the take from prostitutes. To his credit he ultimately made a full public confession, apologized and resigned, the city council and fellow citizens opting not to prosecute. Blankenship moved on to the copper town of Jerome, Arizona Territory, where he hired on as a mine watchman. Recognizing the disgraced lawman’s talents, the local sheriff hired Billy as a deputy, and within a few years Blankenship had redeemed himself, rising to become city marshal of Jerome.

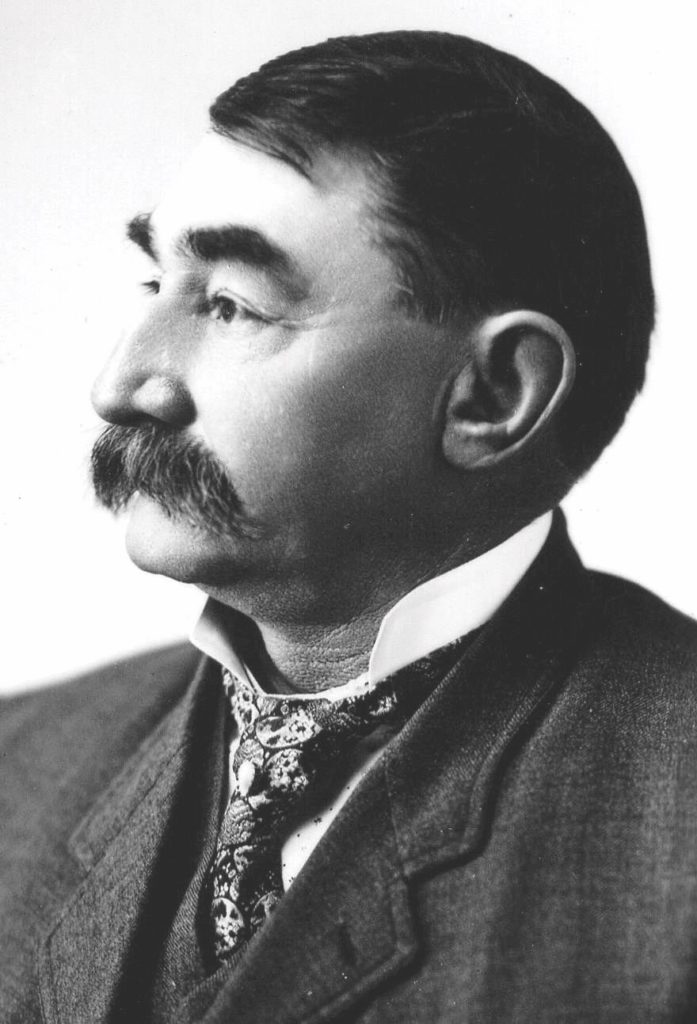

Around the turn of the 20th century in Arizona Territory the big-name lawman was U.S. Marshal Ben Daniels. Daniels claimed a colorful frontier background as a Kansas buffalo hunter; an assistant marshal in Dodge City; a deputy sheriff in Bent County, Colo.; a city marshal in Cripple Creek, Colo., and later in Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory; and a respected member of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, charging up Cuba’s San Juan Heights during the Spanish-American War. No wonder President Roosevelt appointed him U.S. marshal of Arizona Territory in 1902 (see “Rough and Ready,” by Daniel R. Seligman, in the October 2019 Wild West). Shortly after Daniels appointment, however, dirt from his past resurfaced. In his 20s he’d been arrested for stealing Army mules and spent three years in the Wyoming penitentiary. When word reached Roosevelt about the marshal’s buried criminal record, the president asked for his resignation. Fortunately for Daniels, Roosevelt and others believed Ben’s long, distinguished law enforcement career more than compensated for his youthful misdeeds. On the president’s urging the incoming governor appointed Daniels superintendent of the Territorial Prison at Yuma, and in 1905 the president reappointed him U.S. marshal of Arizona Territory—surely one of the strangest twists in Western peace officer history. In his later years Daniels served as sheriff of Pima County.

Taking care of No. 1 was a consideration for many of the lawmen who crossed the line. Patrolman Wylie Lewis of Pasadena, Calif., who was recommended to the post by the chief of police, was a keen observer of homes and stores while walking his beat in 1919. He had a large family but couldn’t make ends meet on his salary, so he cased his routes, borrowed automobiles from friends and robbed right and left for months. He gave new meaning to “putting food on the table,” as he swiped hams, barrels of sugar and a ton of canned goods. He also made off with bicycles, car tires, a brass bed, paintings and clothes. On searching his home, police found among the aforementioned loot “a mask and cap such as are affected by holdup men.” After serving a stint in San Quentin, Lewis ended his days laboring at a Nevada silver mill.

Sometime miner Frank Dyer was appointed U.S. marshal of Utah in 1886 and served for three years. He deftly handled legal issues regarding the Mormon population, notably the many “cohabitation” cases. He was also, to put it politely, a careful man with his money. For example, after charging the government for seed potatoes, he had prisoners plant and weed the tubers, then sold the produce to the government for use as prison rations. He took a similar approach with dairy cows, charging the government for feed, having prisoners tend the cows, then selling the milk to the federal prison. In a report on Dyer’s improper practices the Justice Department suggested he mend his ways.

Among the most intriguing of Western lawmen was Johnny Behan, whose career spanned three decades. He was, among other things, a member of the Arizona Territorial Legislature, a sheriff of two counties, superintendent at the Yuma Territorial Prison, a school inspector, a tax collector and a federal border inspector. Behan is best known, of course, as the Cochise County sheriff who sided with the extralegal Cowboys (some were alleged rustlers) in their dispute with the Earp faction in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Unable to prevent the October 1881 gunfight near the O.K. Corral, he testified at length against fellow lawmen Virgil and Wyatt Earp in its aftermath.

Though certainly no hero, neither was Behan an evildoer, per se. That said, wherever he settled and whatever position he held, controversy seemed to follow. He was perpetually in court, being sued or suing. Behan appeared in court five times to answer felony charges for actions rendered while he was sheriff of Cochise County. Those charges were ultimately dismissed, but they fit a pattern. Dr. George Emory Goodfellow twice took the sheriff to court when Behan tried to collect rent on property he no longer owned. When Behan was discharged as warden of the territorial prison, the newspapers and courts had a field day, exposing him as a horrible administrator. Wherever he popped up, one could count on several things: He would win people over, he would land a plum job (by election or appointment), and during or after his term of office there would be investigations, charges and likely court action.

Though Billy Stiles served at least three stints as an Arizona Territory peace officer, including as a deputy for famed Cochise County Sheriff John Horton Slaughter, it remains something of a joke to list him in the annals of Western law enforcement. Stiles was killing time as a prospector and middling rancher when he teamed with Burt Alvord as a constable in Pearce and then in Willcox, a rough-and-tumble cattle shipping hub. From time to time Alvord deputized Stiles, mostly for saloon work. That was before the shiftless duo hatched their criminal schemes. They robbed two trains, were caught and jailed, escaped and were again caught. When released, Stiles visited Alvord behind bars, and the two again bolted. Soon captured, Stiles was pressed into duty by the Arizona Rangers as a special agent to help track down Alvord. Instead, both fled once more. Eventually settling in Nevada under the assumed name of William Larkin, Stiles became a deputy sheriff in Humboldt County, doing so-so work and soon offending certain parties by turning in one of their cohorts. On Dec. 5, 1908, those parties shot down Deputy Larkin, thus ending his undistinguished three-badge career. As for outlaw-lawman Alvord, he vamoosed for Central America and vanished from the historic record in 1910.

Tom Horn’s name has a poetic ring to it, and in his day he was a prominent frontier personality. He served the Army in the 1870s and ’80s as an outstanding tracker on various sorties against the Apaches in Arizona Territory. He then ranched for a time, served as a deputy sheriff during the territory’s bloody Pleasant Valley War and later hired out as a gun hand (aka paid assassin) for livestock interests on the northern Plains.

Like Behan, wherever Horn went, controversy followed. He easily made both friends and enemies. For some years he worked as a Pinkerton detective out of the agency’s Denver office, though not to great effect. In April 1891 someone robbed a faro game in Reno, and soon thereafter local authorities apprehended Detective Horn on an outbound express train. A search of his person turned up a mask, pistol and money. After the subsequent legal proceedings, however, Horn walked free. According to fellow Pinkerton man Charlie Siringo, the agency knew Horn was guilty but couldn’t afford the hit to its reputation from a conviction. In later years Horn worked as a deputy sheriff and as a hired gun for Wyoming cattle barons. There, in a controversial drunken confession, he reportedly admitted killing a local rancher’s boy with “the best shot I ever made and the dirtiest trick I ever done.” Guilty or not, the folks in Wyoming had had enough. Horn was tried, convicted and hanged in Cheyenne on Nov. 20, 1903.

Ben Thompson was another lawman able to draw on lessons from a checkered past. The Texans who hired him must have figured a gunfighter with experience on the rough frontier was just the sort of guy they needed as a peace officer. British-born Thompson arrived in Texas as a boy and grew into adulthood as a wanderer and sometime gambler who killed several men in Mexico, walked the saloons of Kansas, Texas and points in between, and got into gunplay and other confrontations in Abilene, Ellsworth and other Kansas cattle towns. He knew his way around. Figuring he was ready to work the other side of the law, he ran for city marshal of Austin in 1879 but was voted down. Local politics shifted in his favor in 1880, and the citizens elected him marshal. Though one historian claimed Thompson “seldom spent a sober day on the job,” Austonians were seemingly pleased and re-elected him the following year.

In July 1882, during a family vacation in San Antonio, the marshal encountered longtime nemesis Jack Harris in the latter’s Vaudeville theater and saloon. The pair exchanged dirty looks, and Thompson assumed Harris was going for his gun. “I drew and fired,” he said in justification of his actions. “I was an officer and belonged to a detective agency.” Regardless, the marshal spent months in jail before being acquitted. He declined to continue as Austin city marshal. Two years later Thompson and friend King Fisher, a former deputy sheriff of Uvalde County, were in San Antonio and, in a seeming lapse of good judgment, dropped by the Vaudeville for a drink. The onetime lawmen ran afoul of the theater’s new managers, who still bore a grudge over their friend Harris’ killing. The latter gunned down Thompson and Fisher in killings a court later deemed “justifiable.” So ended the career of a man effective at enforcing the law because he well knew those on the other side.

Sheriff Charles Royer of Grand County, Colo., aspired to a larger role in local political affairs. On arriving in Colorado in 1878, he did some prospecting, raised cattle and even landed a mail delivery contract. The well-liked fellow was elected sheriff in 1879 and re-elected two years later. Royer was said to be “without any bad habits, being always sober and attentive to business.” But the sheriff soon became embroiled in the contentious county seat fight between rival cities Hot Sulphur Springs and Grand Lake. As two commissioners and the county clerk made their way to a meeting at the Grand Lake courthouse on the morning of the Fourth of July, 1883, four masked men emerged from hiding and opened fire. One of the commissioners shot back. Three men were killed in the exchange, including one of the gunmen, who, it turned out, was also a county commissioner. The other three assailants fled. Among them were Royer and his undersheriff. After a cursory investigation, the sheriff disappeared. Twelve days later local papers reported startling news. More Blood: Charley Royer Blows His Brains out in Georgetown, read one abrupt headline. Having bent the law to his purposes, with lethal results, the sheriff seemingly couldn’t live with himself.

A conspiracy involving a shifty Nevada lawman in 1910 centered on “high-grading,” or the illegal removal of gold or silver from a processing plant. Though workers typically smuggled out such ill-gotten gains in lunch buckets or their pockets, the Goldfield Consolidated mill assayer who hatched the scheme had a more covert plan. Conspiring with a mill worker, a prominent local businessman and Bart Knight, a former undersheriff of Esmeralda County turned town constable, the assayer persuaded the Consolidated employee to sneak into the mill at night, scrape gold amalgam off the plates and smuggle it out. The scheme unraveled when a night watchman the men bribed to “look the other way” informed the company detective. The latter hired a stenographer to take notes during a secret meeting attended by Knight in which money changed hands, and the mill worker was later caught in the act. In a case heard before the Nevada Supreme Court, Knight and his co-conspirators faced grand larceny charges. The mill worker testified in return for immunity, and the assayer was convicted. Yet the constable and the businessman managed to keep out of prison, as corroborative testimony was lacking, and their cases were dismissed. But Knight’s career as a lawman was over. Prior to his fall from grace he’d been a leading prospect for county sheriff. When Knight registered for the draft in World War I, however, he was listed as an unemployed resident of Goldfield.

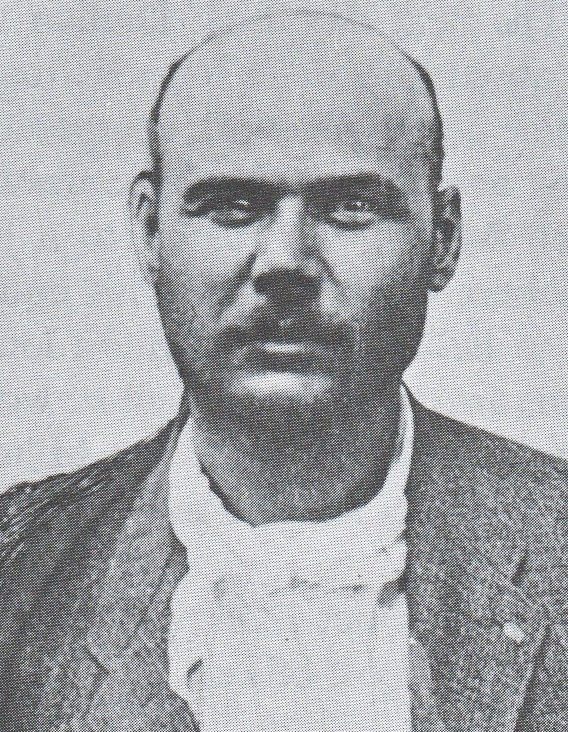

Henry Newton Brown, who was raised in Missouri before drifting further west, worked both sides of the law amid headline-grabbing events on the wild frontier. After his buffalo hunting days he joined up with Billy the Kid’s Regulators during the Lincoln County War in New Mexico Territory and was among the participants in the ambush killing of Sheriff William Brady. A subsequent indictment for murder prompted him to hightail it to Texas, where he became a deputy sheriff of Oldham County. Brown later settled in Caldwell, Kan., where he served as an assistant city marshal, then city marshal. His approval rating was so high that citizens re-elected him several times and presented him with an elaborately engraved Winchester rifle.

On an ego high, perhaps convinced he was above the law, Marshal Brown grabbed his new Winchester, recruited a band of like-minded fellows and headed for Medicine Lodge, Kan., whose bank they’d decided was easy pickings. Things did not go well. On entering the lobby, the would-be robbers got into a deadly shootout in which the bank president and a cashier were killed. Brown and gang fled under fire without a single dollar. A posse soon captured and jailed the fugitives, and a lynch mob came to get them. Bursting through the crowd, Brown almost got away, but a shotgun blast ended his short-lived dual career. In jail he’d penned a note to his wife containing the great understatement, “I didn’t think this would happen.”

Such cases of crossing the line, shifting values or downright evildoing were far from the norm among Western peace officers. On taking the oath, most fulfilled it to the best of their abilities. Texas Ranger John Reynolds Hughes, for one, was an exemplary lawman, boasting a three-decade career spent in the pursuit of criminals and occasional shootouts with them. He went wherever trouble raised its head, from El Paso to Brownsville. In retirement the lawman who lived frugally and saved diligently became the chairman and largest stockholder of an Austin bank. Hughes retains a prominent place in the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame in Waco.

Canadian-born lawman Seth Bullock migrated south to Montana Territory in 1867, was elected to the Territorial Senate and had much to do with early Yellowstone developments. In 1873 he was elected sheriff of Lewis and Clark County. Drawn to Deadwood, Dakota Territory, three years later by business opportunities spawned by the gold rush, he instead accepted an appointment as sheriff. In addition to safeguarding local mining and cattle interests, he proved an effective forest supervisor of the Black Hills Reserve. In 1905 President Roosevelt appointed him U.S. marshal for South Dakota, a position he held for nine years. Decades of service with integrity were the hallmarks of Bullock’s life.

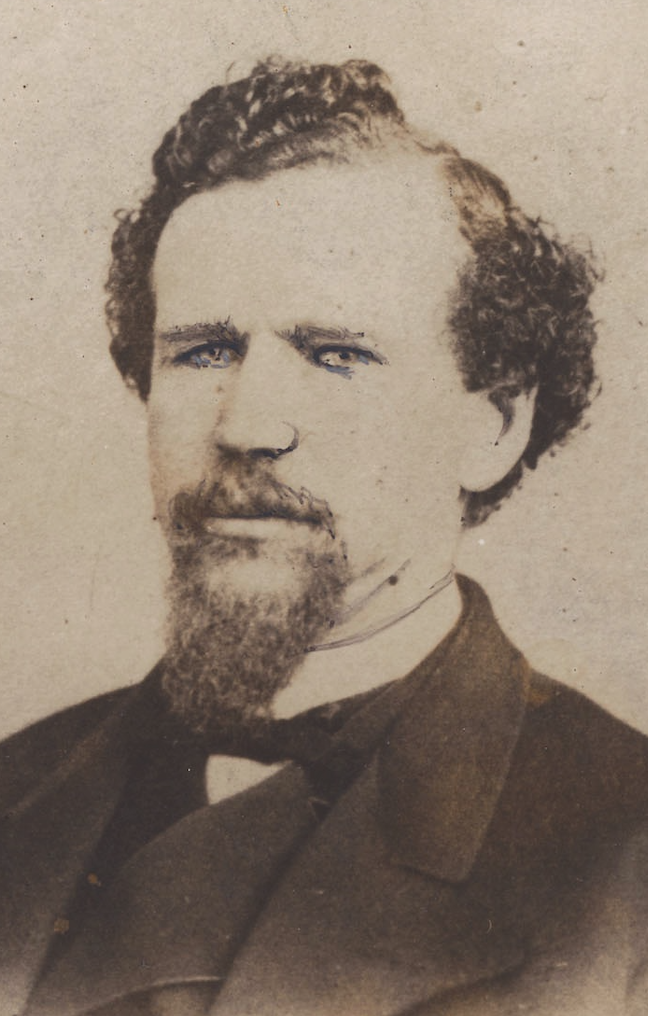

Bob Paul’s career in the far West was also a model of dedication and integrity, beginning with his arrival in the California goldfields in 1848. First elected as a town constable in 1854, he served off and on as a lawman for nearly 40 years. Paul was as a sheriff in both California and Arizona Territory, worked as a special messenger for Wells Fargo and in 1890 was appointed U.S. marshal of Arizona Territory by President Benjamin Harrison. At his death in 1901 he was serving as a justice of the peace in Tucson.

Of course, few Western lawmen were as distinguished as Hughes, Bullock or Paul, let alone approaching the iconic status of such figures as Virgil Earp, Bill Tilghman or Charlie Siringo. But while the majority of mostly forgotten badge wearers may not have had stellar careers, they nevertheless answered the call to service, putting in long hours for low pay while safeguarding their fellow citizens. Thankfully, the dramatic, upsetting sagas of sheriffs planning bank robberies or getting drunk while on the job were the rare exception in the frontier West.