Killer Cousin: The Man that Lured Lincoln to His Doom

JAMES AND HENRY CLAY FORD had a problem. Their brother John had booked into the theatre he owned in Washington, DC, a two-week run by famous actress Laura Keene and her touring repertory company. Keene and fellow players had done well with popular classics such as She Stoops to Conquer and School for Scandal , but ticket sales were sluggish for the final offering of the Washington stand—a popular comedy, Our American Cousin —the night of April 14, 1865. John Ford had decamped to Richmond, leaving his brothers in charge, having overlooked the fact that April 14 was Good Friday, not an evening on which the pious would attend a theatrical performance—or one on which the less pious would want neighbors to see them attending the theatre.

James and Henry Ford had an inspiration. They had hand delivered to the White House a personal note to Mary Todd Lincoln, inviting the First Lady and her husband to be guests that Friday night. The Civil War had ended with Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, and the president was exhausted, trying to find the strategy to reassemble the nation. He just wanted to stay home, but his wife persuaded him that an evening of laughter was the tonic he needed. Her acceptance in hand, the Fords circulated a handbill trumpeting that the Lincolns would be attending Our American Cousin ; the news made the early edition of that day’s Washington Evening Star. Ticket buyers rushed the box office and filled the 1,700-seat house.

Halfway through Act Three, actor John Wilkes Booth, 26, an ardent supporter of the Confederacy, entered the Lincolns’ box and shot the President. Pandemonium broke out, but Keene came onstage, managing both to calm the audience and organize an orderly emptying of the theater. Booth got away and was not captured until April 26. Lincoln died of his wounds at 7:22 the morning after the shooting, the first time an American president had been assassinated.

“Sic semper tyrannis!” After shooting Lincoln,

Booth leaped to the stage, injuring his leg and quoting a phrase from Roman

times before making his getaway down an alley behind Ford’s. (Granger, NYC)

The tragedy made Our American Cousin a footnote in American history. But the play had already achieved a noteworthy spot in popular culture as arguably the best-loved script of its era.

Cousin was a mid-career work by prolific British writer Tom Taylor, for decades a regular contributor to Punch and author of some 100 plays. Our American Cousin debuted as a serious drama in London in 1852—and flopped. But Keene saw the show, recognized the humor hidden in the story, and grasped how to recast Cousin as a comedy that would tickle American audiences. She bought the U.S. rights for $1,000.

KEENE OPENED HER COMEDIC REBOOT in New York in October 1858. Critics rated Cousin as formulaic, but with much to please less-discriminating theatergoers. Fitz-James O’Brien, reviewing the opening performance in Saturday Press , found much fault but ended his assessment, “ Our American Cousin , in spite of all these drawbacks, was greatly relished by the audience, and may be pronounced successful.” Successful indeed. The authoritative multi-volume Annals of the New York Stage published by Columbia University in 1931 observed, “The show set new standards for New York theatre and theatrical success.” The reworked version’s two-week run stretched to 150 performances. Multiple successful productions came and went for the next seven years.

“It was one of those plays that showed American ingenuity,” notes Noreen Brown, a theatre professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. “It said something positive about the American spirit.” Within a year popular playwright Charles Gayler had penned a rip-off that he called Our Female American Cousin , in time unveiling Our American Cousin at Home.

The Woman to

See. Laura Keene had a full house of theatrical cards that she did not

hesitate to play: skilled and seasoned performer, deft and dedicated

impresario, theater owner. (National Portrait Gallery)

The real Our American Cousin takes place at the English country estate of Sir Edward Trenchard. The baronet’s guests include Lord Dundreary, a rather befuddled sort, and widowed Mrs. Mountchessington, towing two daughters for whom she is relentlessly hunting husbands. Problems abound: Sir Edward is busted and Richard Coyle, his estate agent, is threatening to plunge him into bankruptcy if he does not repay an old loan. Coyle offers an out: he will destroy the loan document provided Sir Edward lets Coyle marry Sir Edward’s daughter, Florence. Florence, of course, not only detests Coyle, but is in love with Navy lieutenant Harry Vernon. The couple cannot marry until Vernon gets his own ship; Lord Dundreary has the connections to make that happen but refuses to help.

THE PLAY BEGINS with the Trenchard family absorbing startling news. Sir Edward’s Uncle Mark, who had quarreled with his children years before and moved to the United States, has died. In the States Mark reconnected with a Vermont branch of the Trenchard family that had moved to the New World in the mid-1600s. Still angry at a now deceased daughter for marrying without his consent, Uncle Mark, rather than let his British holdings—now worth some $400,000—go to the dead daughter’s child, has left the inheritance to a young man from the American branch. And that fellow, Asa Trenchard, is at that moment on his way to collect the fortune.

Asa, described by one writer as “noisy, coarse, and vulgar, but honestly forthright and colorful,” arrives and throws everyone into a tizzy with his peculiar vocabulary and apparently complete ignorance of the manners of society.

But over the next two acts his inventiveness and good heart manage to solve the Trenchard family problems. “I’m a rough sort of character, and don’t know much about the ways of great folks,” Asa muses. “But I’ve got a cool head, a stout arm, and a willing heart, and I think I can help.”

Asa finds and filches Dundreary’s hair dye, holding the goop hostage until the peer gets Florence’s beloved command of a Royal Navy ship. He sneaks into Coyle’s office and finds documentation that the debt Coyle has been holding over Sir Edward’s head has long since been retired. He threatens to expose Coyle’s skullduggery unless the estate agent covers all of Sir Edward’s debts and then resigns so Coyle’s much put-upon clerk can become Sir Edward’s estate agent.

And to cap the evening, Asa even aids Mrs. Mountchessington in getting one of her daughters betrothed to Dundreary.

this article first appeared in American history magazine

Facebook @AmericanHistoryMag | Twitter @AmericanHistMag

There’s one more character: Mary Meredith, Uncle Mark’s shortchanged granddaughter. She’s living on the estate too, as a milkmaid, tending a small herd of cows and a flock of chickens and selling butter and eggs. She’s poor but an uncomplaining and happy soul. Pretty, too. She so enchants Asa he burns the will leaving him the English fortune. With no will, the boodle goes to the late Mark’s next of kin, Mary. Asa’s selflessness has a payoff when Mary accepts his proposal of marriage.

IT 'S NOT RANDOM that Cousin Asa hails from New England. The unsophisticated but clever and compassionate Yankee had long been a staple of American stage comedies in which a protagonist solves problems bedeviling folks richer and better educated but much less imaginative. Pulitzer Prize- winning cultural historian Howard Mumford Jones noted that this stock character had “the heart of gold which the Americans associate with a shagbark exterior.” The combination of simplicity and practicality was the way citizens of the new nation liked to see themselves. The character may have been standard but in that capacity served as “a generic folk figure capably illustrating cheeky traits of the American temper,” explains Richard M. Dorson, long-time director of the Folklore Institute at Indiana University. “His words, like his manners, smacked of the farm and the countryside,” chock full as they are of vernacular slang and social goofs, Dorson said.

The stereotype’s origins lay in the first produced play by an American citizen, Royall Tyler’s 1787 The Contrast. As an avatar the character Jonathan, an honest bumpkin working as a servant to a Revolutionary War hero, is peripheral to Tyler’s story of mismatched engagements.

But Jonathan’s comic woes navigating Manhattan and interacting with upper crust Gothamites became a template for later playwrights. He mistakes a streetwalker for a deacon’s daughter. He roars boisterously at anything he finds funny and proves an incapable student when another servant tries to pass on the rules of polite laughter. And Jonathan speaks a stage exaggeration of Yankee lingo; after kissing a maid, he struggles to explain the resulting joyous feeling: “Burning rivers! Cooling flames! Red-hot roses! Pig-nuts! Hasty pudding and ambrosia!“

After falling out of favor, Our American Cousin began to enjoy a renascence as a historical oddity and enjoyable evening of theater.

VERSION BY VERSION , in the decades after The Contrast , that clever

rustic evolved from second banana to the spotlight role. The core humor in

these fish-out-of-water comedies derived from cultural clash. The homespun

simplicity of the untutored American and the effete culture of the upper-class

British—and their mutual misunderstandings—may have in Our American Cousin

been exaggerated for comic effect but the set-up contained enough grains of

truth to elicit belly laughs of recognition. For example, told that an English

relative who was visiting Vermont had gone on a hunting trip, a character

comments, “Yes, shooting the wild elephants and buffalo what abound there.”

And the heroine, trying to imagine her soon-to arrive American cousin’s looks,

says, “They are all about 17 feet high in America, ain’t they? And they have

long black hair that reaches down to their heels.”

When Asa presents himself at his relative’s manor house, the butler explains, “He didn’t tell me his name, and when I asked him for his card he said he had a whole pack in his valise, and if I had a mind he’d play me a game of Seven Up.” Offered lunch, Asa answers that, on the way, “I worried down half a dozen ham sandwiches, eight or ten boiled eggs, two or three pumpkin pies and a string of cold sausages, and, well, I guess I can hold on ’til dinnertime.” Encountering his first shower bath, Asa can’t figure out the gizmo. He pulls the cord thinking it will summon a servant to explain, drenching himself. ALL THE WAY Through Cousin , Asa speaks in a backwoods slang that might convey more than a hint that he might be putting those precise English folks on. This trace of uncertainty delighted audiences. He calls the widow trying to fix him up with her daughter a “sockdologizing old man-trap.” At one point he describes himself as “all-fired tuckered out.” Wooing Mary, Asa swears to the object of his interest, “I’m filling over with affections which I’m ready to pour out all over you like apple sass over roast pork.”

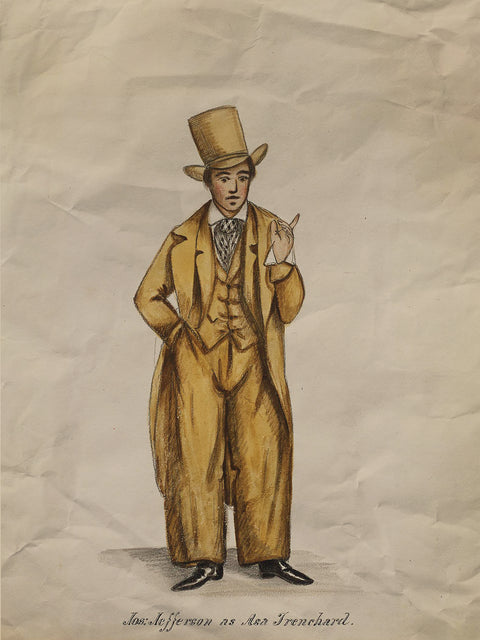

Joseph

Jefferson (National Portrait Gallery)

The part of Asa originated with Joseph Jefferson. At 29, Jefferson had been eking out a living as an actor since age three; being cast at Asa made his career. Not only was the play a hit, but Jefferson brought into being a new performing style that dropped set stage conventions, presenting Asa as a real person with feelings and not just a walking, talking collection of punch lines.

After other triumphs, Jefferson signed on with a theatrical adaptation of Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle. His work in the title role was such a sensation that he continued to play that part—and seldom any other—in various productions for the last 30 years of the 19th Century.

Jefferson persuaded English actor Edward Askew Sothern to play Lord Dundreary in Our American Cousin. Sothern, the talk of Manhattan for his performance in Camille , hesitated to take on what was essentially a minor character, feeling the part was too small for his new-found fame. Jefferson’s retort: “There are no small parts, only small actors.” He was right. The public adored the way Sothern played the vain, stupid titled gentleman, with his unique way of twisting aphorisms—“birds of a feather gather no moss,” for example. Sothern kept adding shtick to his portrayal, delivering lines with a lisp, adding coughs and grimaces, and inserting ad libs. His Dundreary became a popular sensation, as retailers hawked Dundreary scarves, Dundreary shirts, and Dundreary collars based on his stage attire. Sothern went on to a distinguished career on both the New York and London stage, intermittently returning to the footlights as Dundreary in at least three copycat vehicles.

Edward Askew Sothern in

character as Lord Dundreary. (Library of Congress)

NEITHER JEFFERSON NOR SOTHERN were in the Our American Cousin company that performed at Ford’s that fateful night in 1865. But the star of the original production was there, billed in big type above the title for the Ford’s performance. Her part was neither the biggest nor the most demanding, but there is no doubt that she was the dominant figure. Laura Keene was one of the most popular actresses of the time, as well as a major force in American theatrical life. No other woman had achieved a presence anywhere near hers. She not only owned the American rights to Our American Cousin but also designed and owned the theatre where that vehicle’s comic reworking premiered in the States and ran the company that performed there.

Englishwoman Keene, born Mary Frances Moss, was left at age 25 with two children and no means of support when her husband, convicted of unspecified crimes, was transported aboard a prison ship from England to confinement in Australia (“Hard Labor,“ June 2019).

Moss’s aunt was the actress Elizabeth Yates, who opened the door for her niece to take to the stage. Using the name Laura Keene, the young performer immediately displayed a natural talent, in her first year as an actress appearing at three London theatres. She attracted the attention of James Wallack, who lured her to the States to be the lead actress in his stock company. She debuted in New York in September 1852 and quickly developed a devoted fan base.

Keene was no beauty, with features heavier than deemed ideal, but, Jefferson acknowledged, “Her rich and luxuriant auburn hair, clear complexion and deep chestnut eyes, full of expression, were greatly admired. It was her style and carriage that commanded admiration, and it was this quality that won her audience. She had, too, the rare power of being able to vary her manner, assuming the rustic walk of a milkmaid or the dignified grace of a queen.”

BUT KEENE, AMBITIOUS AND BOLD , wanted much more than avid fans. At the end of 1853, she relocated to Baltimore, Maryland, arranged a three-month lease on the Charles Street Theatre, and not only starred in plays there but directed shows and managed the theatre. “While theatrical management was a risky endeavor compared to the relatively secure position of a leading lady in a first-class New York Theatre, it offered great potential for power and profit,“ writes Wake Forest College professor Jane Kathleen Curry. “As a manager Keene would be able to control play selection and casting, hire all performers and staff, supervise all elements of production, and by assuming financial risk, take a chance of gaining greater financial reward.”

After ventures in Australia and California, Keene returned to New York in 1855 and took over the Metropolitan Theatre, renamed it Laura Keene’s Varieties, and again directed and starred in a string of plays. She proved a tough cookie. She put scenery on her stage and costumes on her actors that were far more detailed than the norm. She aggressively promoted her productions, running ads twice the size of those other theatre managers placed. And she drew theatergoers by hiring away popular actors from other companies. “Laura Keene was known to possess the coolest head in the theatre industry,” historian Mark A. Lause wrote recently. Other managers—already openly unhappy that a woman was muscling into their ranks—kept her busy in court parrying breach of contract suits.

Queen Keene’s Palace. The Keene, located on

Broadway just above Houston, became the only theatre in town to maintain its

own full company of actors and to stage plays all summer. (Corbis

Historical/Getty Images)

But none of the theatres she had managed fit Keene’s conception of what a theatre should be. So she lined up investors, hired architect J.M. Trimble, and plunged into building her own. The Laura Keene Theatre, on the east side of Broadway just above Houston Street, won raves when it opened with As You Like It on November 18, 1856.

“The hall is paved with black and white marble, and looks elegant, especially at the part where it is surmounted by the ornamental dome,” The New York Times told readers the following morning. “The stage itself appears to be unusually well-proportioned and is fifty-two feet in depth. Most of the decorations of the house are in white and gold with the exception of the ceiling, which is beautifully and elaborately painted with allegorical figures.” The Keene became the only theatre in town to maintain its own full company of actors, alone in presenting plays throughout the summer. Our American Cousin remained a staple of the facility’s repertoire.

AFTER THE ASSASSINATION , given that Lincoln’s slayer was an actor, the entire Our American Cousin cast at Ford’s came under suspicion. Booth had had nothing to do with Keene’s troupe, but she and other members were arrested. She quickly convinced authorities that she had no connection to the killing and resumed her tour in Cincinnati. In 1869, she took over management of the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia for six months, then resumed touring with her company. But she was slowly weakening from tuberculosis and gave her final performance on July 4, 1873. She died exactly four months later, at 47.

After Lincoln’s assassination, Our American Cousin immediately went from widespread popularity to cultural exile; producers assumed Americans would find nothing funny about a play with such horrid associations. Edward Askew Sothern was beloved enough as Lord Dundreary that he managed to mount two revivals in the 1870s, but that was pretty much it—until memory shifted. Over the decades the sense that Cousin was cursed drained away and the script was such an effective laugh machine that some show business personalities began testing the waters reviving it.

National Shrine. Ford’s Theatre, on 10th Street NW

in the nation’s capital, remains a very popular tourist stop but steadfastly

refuses to restage the theatrical vehicle that drew Abraham Lincoln to his

violent death. (Ian Dagnall Commercial Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

The ultimate proof that Our American Cousin no longer was a pariah of a play came on December 12, 1907, at the Belasco Theatre in Washington, DC. E.H. Sothern, after years of touring in period costume dramas and the plays of Shakespeare, took on his famous father’s most famous role, the buffoonish Lord Dundreary. To denature the play’s notoriety Sothern the younger retitled it Lord Dundreary, fooling no one. (Newspaper coverage referred to the play as Our American Cousin.) “The audience enjoyed the performance immensely, laughing as heartily over the jokes as their forefathers before them,” reported The New York Times. But the most significant proof that time had dispelled the gloom enveloping the play was that sitting in a proscenium stage box were President Theodore Roosevelt and wife, Edith. (In 1915, Sothern fils played in the show on Broadway for 40 performances.)

Our American Cousin’ s unsophisticated structure grew long in the tooth and

vanished from the boards only, like Cousin Asa getting himself or someone else

out of a jam, to find in the 21st Century new life as a blend of historical

oddity and enjoyable night of theatre. The scene of the crime, restored as an

active showplace in 1968, rebuffs frequent calls to mount the comedy; that

“would make Ford’s too much of a monument

to what an assassin did there,” management explains. Others see it

differently.

Vanity Fair contributing editor Bruce Handy recently wrote that “the play had a charming deliberate goofiness, a sense of humor about its own dumbness, that is not so far removed from the tone of a lot of contemporary film comedy.” In 2009, the bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth, Monmouth College’s theatre staff had success staging the play in nearby Galesburg, Illinois, where in 1858 Lincoln debated Stephen Douglas in his failed bid for a Senate seat.

Then in 2015, the assassination’s 250th anniversary, a surge of revivals included stagings in Pittsburgh, Richmond, and Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois. Those productions may have had about them a whiff of historiography, but the play really doesn’t need that.

“After 150 years, the plot line is still capable of capturing the imagination of a wide audience,” argues Morgen Stevens-Garmon, associate curator of the theatre collection of the Museum of the City of New York. In 1861, the play had been a huge success in London, running a phenomenal 500 performances. Its renewed and continuing viability was proved in 2015, when London’s Finborough Theatre found such enthusiasm for a revival that management had to schedule extra performances. All were completely sold out.

This article appeared in the Autumn 2022 issue of American History magazine.

GET HISTORY 'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit