How Volunteer Soldiers Blocked Robert E. Lee — By Burning the World’s Longest Covered Bridge

They were inexperienced in combat. Most were common laborers in a local rolling mill who had recently left their jobs to defend their workplace, homes, and loved ones. Now they were in an unpaid home guard company defending the world’s longest covered bridge against oncoming Confederates. None wore uniforms, but each of the 53 volunteers had army-issued muskets on hand as they wielded pickaxes and shovels to strengthen the horseshoe-shaped earthworks and rifle-pits surrounding Wrightsville, Pa. They ranged from 15-year-old John Aquilla Wilson to several older men who had seen plenty of sunrises. Some feared they might never see the sunset on this day if the Rebels captured them. All were Black.

It was Sunday, June 28, 1863, and the sight of Black men marching to war against Confederate forces was still new in southern Pennsylvania. Some of the guardsmen had relatives and friends who earlier in the year had left Wrightsville and neighboring Columbia to enlist in the newly organized 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry regiments. Unlike their comrades, the men digging trenches were not a formal military unit but volunteers in the home guard company—the only Black unit among five such amateur organizations from towns along the Susquehanna River. They made up in courage and determination for what they lacked in martial training. “They presented a motley appearance, attired as they were in every description of citizens’ dress,” wrote an admiring Lieutenant Francis Wallace of the 27th Pennsylvania Volunteer Militia (PVM), a newspaper editor in civilian life. “They were armed with the old musket altered to the percussion lock.”

The Black company from Columbia, under the command of rolling mill co-owner Captain William Case, was part of a 1,500-man force hastily assembled in the days before the Rebels were due to arrive. Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, working with the War Department and Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch of the Department of the Susquehanna, had called for 50,000 volunteers to defend the commonwealth once news arrived that elements of Robert E. Lee’s vaunted Army of Northern Virginia were crossing the Mason-Dixon Line. Couch did not have the authority to enroll Black men into the seven for-pay PVM regiments that were mustered into the service, so the Columbians and York Countians served on their own volition, without compensation, uniforms, or equipment, other than the entrenching tools and muskets that the quartermaster of the 27th PVM had distributed.

Their foes were battle-tested veterans, the lead brigade of Confederate Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Division that had occupied York, the largest town between Harrisburg and Baltimore, earlier that Sabbath day. On June 27, Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon’s brigade of six Georgia regiments rested in fields near the hamlet of Farmers Post Office, some 10 miles west of York on the turnpike to Gettysburg. That evening, General Early rode south from where his three other brigades were camped at Big Mount to meet with Gordon. The tall Georgian informed his commander that a delegation of York’s civic leaders had visited his camp and agreed that the Union troops defending the town would withdraw, leaving the borough of 8,600 people open to Confederate occupation without any resistance. “If that proves true,” Early ordered, “you will pass on through and move rapidly to the river to secure both ends of the Wrightsville-Columbia bridge.”

Early had orders to burn the 1¼-mile-long wooden bridge and take his division northwest from York to Dillsburg, where he could support Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s efforts to capture Harrisburg should that prove to be practical. When he embarked on his second major invasion of the Northern states on June 3, Robert E. Lee, as he had done in his Maryland Campaign of September 1862, hoped to strike a crippling blow to Union morale, either by seizing a major city or drawing the pursuing Army of the Potomac into a battle on ground of his choosing that might end in a decisive Confederate victory. That favorable result might force President Abraham Lincoln’s administration to negotiate an end to the bloody war. One particularly enticing option that Lee considered was to occupy Pennsylvania’s capital. With that in mind, he instructed his Second Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, “If Harrisburg comes within your means, capture it.” The order left room for Ewell’s discretion, depending on the circumstances he might encounter.

As in his earlier incursion into enemy turf, Lee audaciously divided his army to facilitate achieving his goal. Marching north on June 27 from the Chambersburg area, Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes’ Division of the Second Corps seized Carlisle. Well in advance, Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins, commanding Ewell’s mounted infantry brigade, secured Mechanicsburg, from which the Confederates could threaten Harrisburg from the west. There remained a problem, however—Harrisburg was situated on the eastern bank of the Susquehanna River. Any attempt to seize the capital would require a frontal assault on the thousands of New York and Pennsylvania militiamen who defended the heights on the western shore. Thus, Ewell sent Early’s division east through Gettysburg to seize York, a valuable prize with its railroad warehouses, road network, and general prosperity.

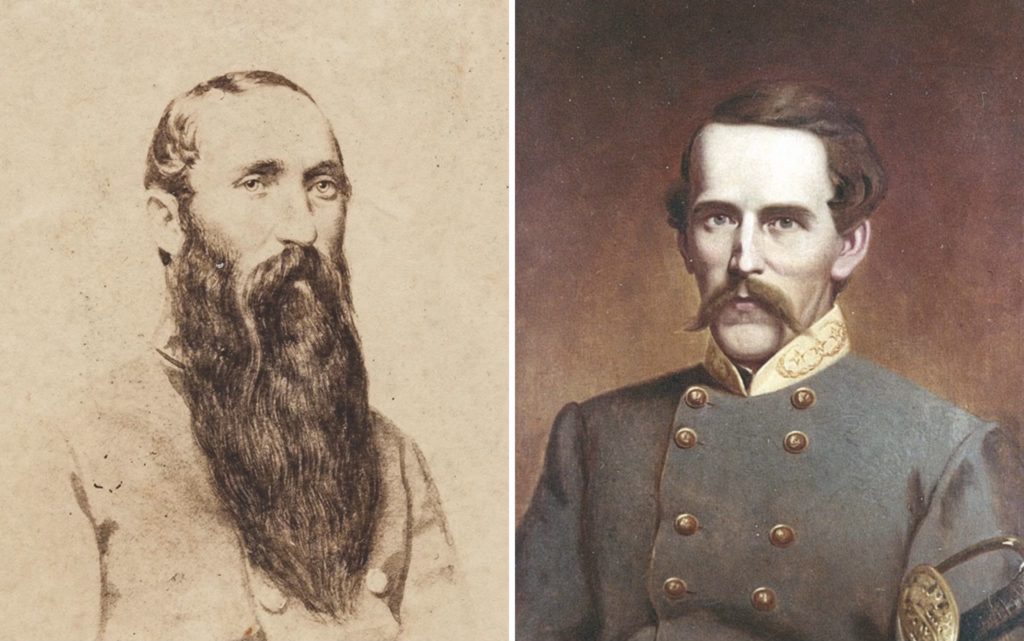

On June 26, Early drove the defending 26th PVM from Gettysburg, capturing 175 soldiers without losing a man. He deemed the state emergency militia “so utterly inefficient” that, on his initiative, he decided to seize the Columbia Bridge instead of destroying it as ordered. So, on Saturday night on the Jacob Altland Farm at Farmers, Early issued his orders to Gordon to secure the bridge. As he later wrote, the crusty Virginian now planned to march across the river into Lancaster County, seize the 1,000 horses rumored to have been taken to safety there, and then march up roads paralleling the eastern riverbank to threaten Harrisburg’s relatively undefended rear.

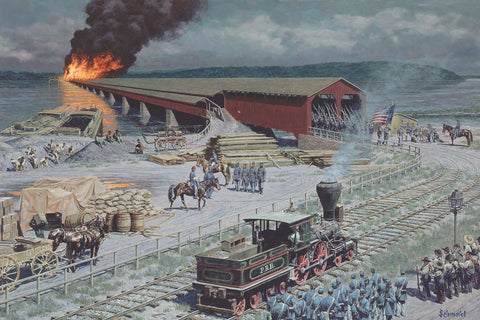

The Columbia Bridge was a prize worth controlling. A series of ferries had served travelers between Wrightsville and Columbia from colonial days until 1812 when businessmen in the latter town had commissioned a toll bridge. Ice floes had knocked it off its foundations two decades later and partially wrecked it. The replacement bridge, opened in 1832 using much of the wood from its predecessor, spanned 5,620 feet. The massive, 40-foot-wide structure contained a roadway for the Philadelphia–Pittsburgh turnpike, tracks for the Pennsylvania Railroad that intersected the Northern Central Railway at Wrightsville, and a two-level towpath that connected the Pennsylvania Main Line Canal in Lancaster County to the Susquehanna and Tidewater Canal along the western riverbank in York County.

The Columbia Bank, the bridge’s owner, made a hefty profit charging tolls to cross the river—$1.50 for a wagon and six horses; 6 cents for each pedestrian. Strategically, it was the only bridge between Harrisburg and Conowingo, Md., and the few viable fords in York County were unusable because recent rains had swollen the river.

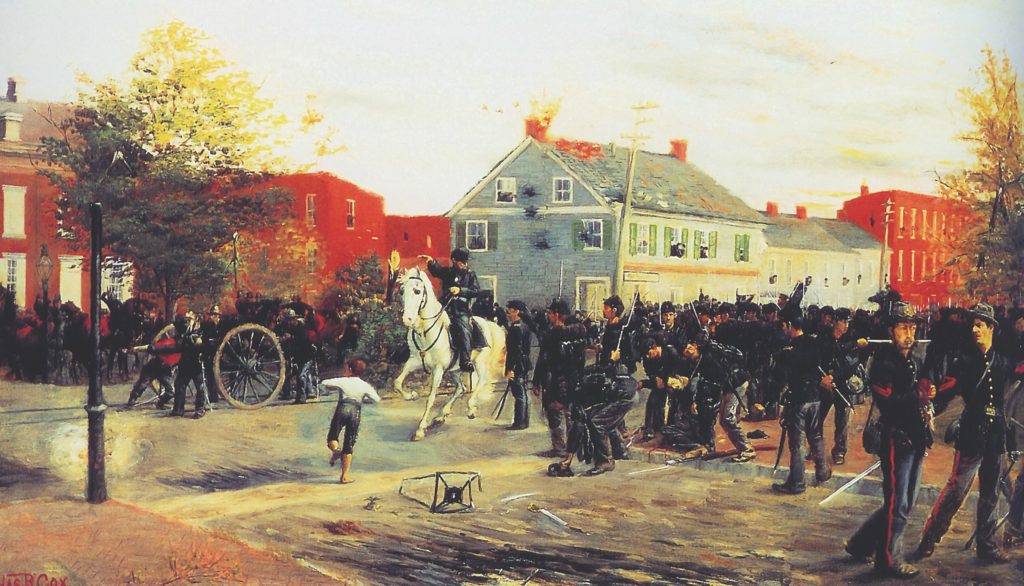

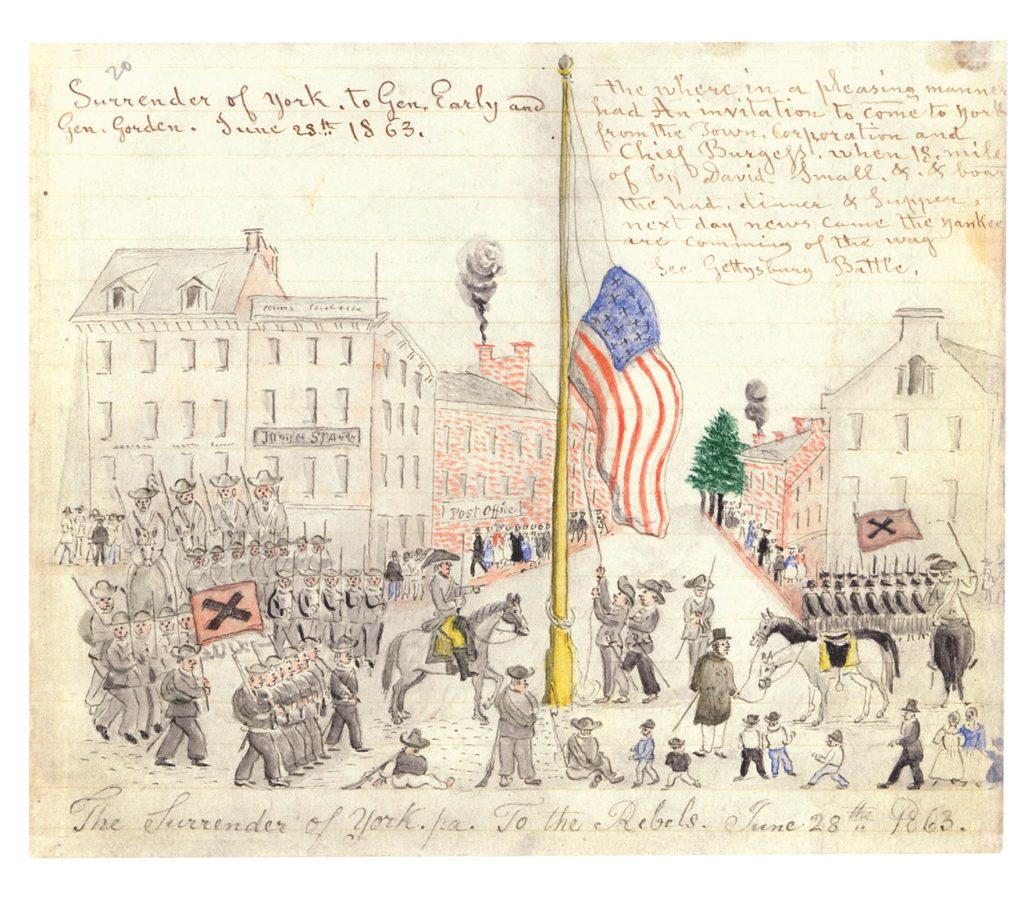

Gordon’s Brigade, which Ewell tasked with quick-marching eastward to take the vulnerable bridge, consisted of the 13th, 26th, 31st, 38th, 60th, and 61st Georgia Infantry. York’s Democratic chief burgess, newspaperman David Small, had negotiated with Gordon on Saturday night, so Gordon knew as he marched east from Farmers on Sunday that he likely would take York without firing a shot. Behind a small screen of Virginia cavalry, Gordon’s pioneers and the 50-man vanguard of the Colonel Clement A. Evans’ 31st Georgia arrived in York at 10 a.m as church bells summoned the citizens to Sunday worship services. Most rushed into the streets or had already decided to skip church to watch the oncoming procession. Many had hidden or buried their valuables, and the banks had sent their holdings to safety.

Confederate bands played in the distance as Captain William Henry “Tip” Harrison led the first soldiers into town to guard the crossroads and prevent interference with the long column of 1,800 Georgians coming from the west. Some of Gordon’s early arrivers hauled down an 18- by-35-foot handmade U.S. flag that flew from a 110-foot-high pole in York’s Centre Square. Some accounts suggest that Gordon threw it across his saddle; others say he folded it in his saddlebag. One story, likely apocryphal, says he tied it to his horse’s tail and dragged it through the muddy streets. The sight reportedly so enraged a local lad, Adam Spangler, that he ran home to find a gun to kill the Rebel general. His father wisely advised him that such an act could lead to a massacre of the townsfolk.

A couple of blocks east of the town square, a girl, who Gordon reckoned was about 10 to 12 years old, handed him a bouquet of red roses. In it, he discovered a folded piece of paper in “a woman’s flowery handwriting” that gave a detailed description of Wrightsville’s defenses. “I carefully read and reread this strange note,” Gordon later wrote. “It bore no signature and carried no assurance of sympathy for the Southern cause, but it was so terse and explicit in its terms as to compel my confidence.” The girl, Mary Ann Small, likely had received the flowers from a stranger with instructions to give them to the general. Her parents were not known as Southern sympathizers.

When other elements of his division arrived to secure York, Early dispatched Gordon’s Brigade on his mission to Wrightsville, marching behind much of Lt. Col. Elijah V. White’s 35th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, and the four 3-inch ordnance rifles of Captain William A. Tanner’s Courtney (Va.) Artillery. Gordon proceeded slowly toward the river, pausing to give his men an extended lunch break just east of York. Early’s other three brigades (Brig. Gen. William Smith’s, Brig. Gen. Harry Hays’, and Colonel I.E. Avery’s) and his three other artillery batteries remained in the York area. “Old Jube” demanded that the townspeople furnish $100,000 in cash and massive amounts of shoes, food, and supplies. He would collect most of the requisitioned provisions and footwear but garner only $28,610 from door-to-door solicitations by civic officials.

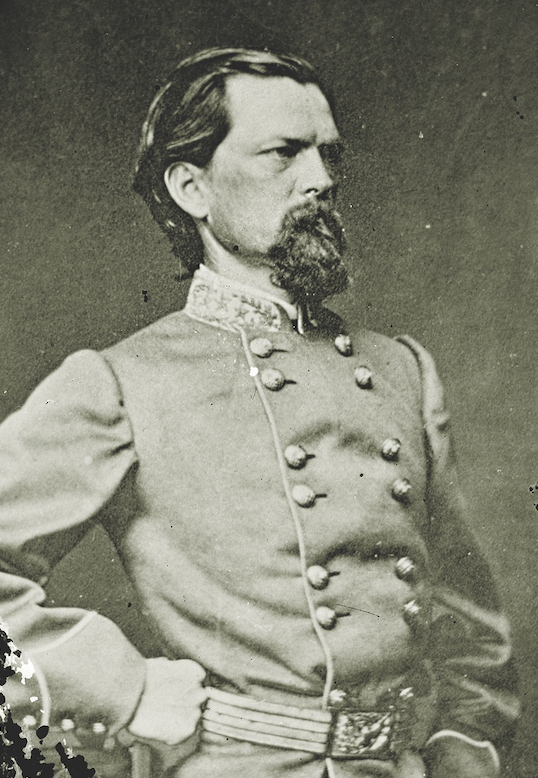

Gordon, Early’s most reliable subordinate, was a talented, experienced leader of men. Born in Upson Country, Ga., on February 6, 1832, he had attended the University of Georgia but had not graduated. He was a lawyer and businessman with no military training when the war broke out. From his first fight at Seven Pines on May 31, 1862, Gordon displayed natural leadership qualities, as well as single-minded devotion to duty. He also possessed uncanny durability, surviving a wound at Malvern Hill on July 1 of that year and five more wounds while defending a portion of the Sunken Road at Sharpsburg (Antietam). His promotion to brigadier general was approved in the spring of 1863. He fought well at Chancellorsville in May and again in June at Second Winchester, where his spirited attack had helped break the Union lines on the first day of that battle.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Ahead of Gordon at Wrightsville, Major Granville O. Haller of the 7th U.S. Infantry led a motley force of some 1,500 men assembled to defend the river crossing. The York native had commanded McClellan’s headquarters guard at Antietam but had been at home recuperating from illness when General Couch tapped him to command the defenses of Adams and York counties. Born in York on January 31, 1819, Haller was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 4th U.S. Infantry in 1838 and then fought the Seminoles in Florida in 1840–41 and the Mexicans in 1846–47. He served in the battles of Monterrey, Veracruz, Churubusco, and Molino del Rey, sometimes alongside a fellow officer in the regiment, 2nd Lt. Ulysses Grant. Transferred to the Washington Territory in 1853, Haller fought the Yakimas from 1855 to 1856, and was ready to fight the British, if necessary, during the 1859 border standoff on San Juan Island known as the “Pig War.”

Haller had arrived in Wrightsville on Saturday evening on the last train out of York, bringing the stunning news that the borough’s leaders would surrender the town to Early. One of his first acts was to convince the bridge’s owners to suspend the collection of tolls. Massive lines of refugees crowded the streets, anxiously waiting their turn to pay to cross the Susquehanna to presumed safety. Haller wanted the avenues left clear for troop movement. It would prove to be a wise decision.

About 650 of the defenders of Wrightsville were from Colonel Jacob G. Frick’s 27th PVM, augmented with elements of the 20th and 26th PVM that had earlier retreated from Hanover Junction and Gettysburg, respectively. In addition, Haller had at his disposal some 200 ambulatory patients from the U.S. Army General Hospital in York (mostly wounded or ill veterans of the Army of the Potomac); about 50 refugees from the 87th Pennsylvania of the 8th Corps who had fled to York after that regiment was dispersed at the Second Battle of Winchester; the 53 Black home guardsmen; Captain Robert Bell’s Adams County Independent Cavalry; and the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry.

Colonel Frick had considerable previous experience in battle. Born in Pottsville, Pa., on January 23, 1825, he entered military service in June 1846 as a 3rd lieutenant in the 3rd Ohio Infantry during the Mexican War. He subsequently received a Regular Army commission and, when the Civil War erupted, he became the lieutenant colonel of the 96th Pennsylvania. He performed well during the Seven Days Campaign.

On July 29, 1862, Frick took command of the 129th Pennsylvania. During the ill-fated Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, he led the regiment in an uphill advance until finally driven to the ground near the stone wall. Frick distinguished himself again at Chancellorsville. Confederates seized the regimental flag, but Frick countercharged and recovered it. He would receive a Medal of Honor in 1892 for his valorous leadership at the latter two battles. He and his men mustered out in May 1863 when their terms of service expired.

Now, with the Confederates threatening Pennsylvania, Frick and many of his officers and surviving men enlisted in the new 27th PVM, bringing some stability to the largely inexperienced recruits. Arriving on June 22, he set about strengthening the crescent-shaped line of earthworks west of Wrightsville. Railroad workers, civilian volunteers, and college students had begun work on the entrenchments and rifle-pits a week earlier. Now, his men from north-central Pennsylvania set aside their weapons and worked to expand and deepen the works. Haller and Frick ordered men to roll railcars to the bridgehead, where soldiers overturned them to barricade the entrance. They left just enough room to pass between the cars in a single file. That should stop the Confederate cavalry, which is all they thought would attack the bridge. No one at that time imagined a full-scale invasion with an enemy infantry brigade as the opponent.

Once reports arrived on June 26 that Early’s entire division had turned eastward and now was in Gettysburg, with the bridge possibly in their crosshairs, Haller and Frick knew they had little chance with their relatively untrained force to defeat the Rebels. Together, they worked out a contingency plan involving a swift retreat across the bridge. Haller had three artillery pieces in Columbia with which to blow holes in the bridge deck in the event of an enemy advance, but his men lacked ammunition. Hence, carpenters and volunteers from Columbia bore holes in the bridge’s superstructure; Frick envisioned blowing up the fourth section from the Wrightsville side with charges of gunpowder, dropping the 200-foot span into the water. If that did not work, he planned to have barrels of coal oil rolled on the bridge from a Columbia merchant. Soldiers, in that case, would douse the bridge deck and stacks of kindling. Because the bridge was privately owned, Frick and Haller decided to have civilians associated with the Columbia Bank apply the torch, not government soldiers.

At 5:30 p.m. on June 28, Wrightsville’s defenders saw a long line of Confederate skirmishers cautiously approaching across the unfamiliar wheat and cornfields. As the 31st Georgia began probing the defenses, Gordon sent two strong columns on each side of the enemy lines to turn their flanks if possible. He ordered Captain Tanner to unlimber his artillery pieces, sending sections to hills on either side of the turnpike. They would fire some 40 shells into Wrightsville over the next hour. By then, Haller had retired to Columbia to wire an update to General Couch in Harrisburg, leaving Frick in tactical command of the field.

Frick, knowing the position was rapidly becoming untenable, began disengaging his forces. He conducted a hasty withdrawal through Wrightsville and across the bridge. Nearly all of his men reached safety, except for a lieutenant colonel and 19 militiamen who were taken captive before they could cross. A fragment of one of Tanner’s shells decapitated one of the Black defenders from Columbia, making the unidentified man the only fatality of the skirmish at Wrightsville. Gordon reported only one of his infantryman wounded. “The regiment held out well,” bragged Private Joseph B.W. Adams of Company D, 27th PVM, in a July 9 letter to The Pittston Gazette, “till the rebels were seen to be out flanking them, with the intention of occupying the bridge, cutting off our retreat and capturing all hands. On this, Colonel Frick led the Regiment over the bridge, amid fire of the enemy’s cannon, and then set fire to the bridge.”

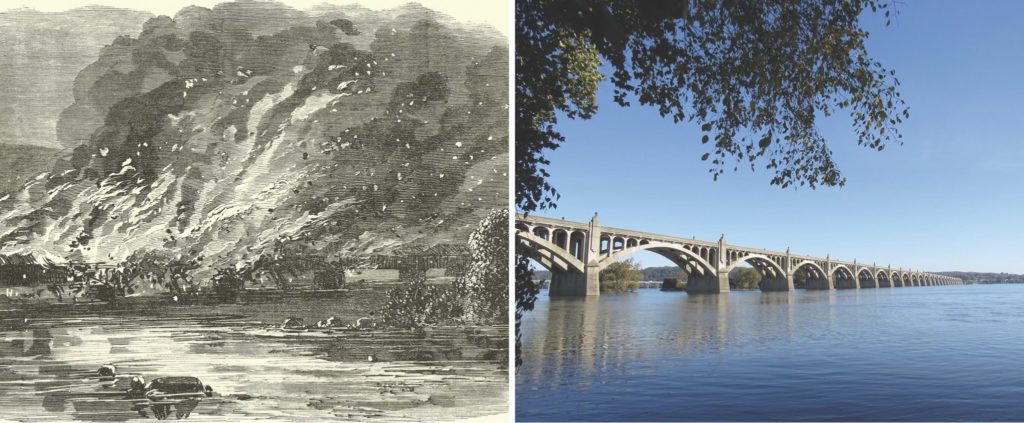

Once most of his troops were safely in Columbia, Frick ordered the powder charges detonated, but they only splintered some portions of the support arches and blew holes in the roof and sidewalls, leaving the bridge deck still passable. As Gordon’s troops approached the riverside, Frick ordered the oil and kerosene–soaked timbers set alight. “I myself being on guard on this side of the river, was safe from the shells, but I could see them dropping in the river,” observed Private Adams. “The fire from the burning bridge was a splendid sight rolling up the fiery clouds toward the heavens. It was a sad necessity to destroy this beautiful structure, but it was our only course, to prevent the destruction of our regiment.” He concluded, “None killed, and all in good spirits, ready for them again. The boys say they were fired on during the retreat, by the copperheads of the town, and that one lady (or female, rather) displayed a small Confederate flag.”

The fire, once started, spread quickly. The wind shifted, blowing embers into the eastern edge of Wrightsville. “I called on the citizens of Wrightsville for buckets and pails, but none were to be found,” Gordon later wrote. “There was, however, no lack of buckets and pails a little later, when the town was on fire.” Long lines of his men passed water uphill from the river and canal into Wrightsville, limiting the destruction to a few houses, the post office, a millinery, two lumber yards, and a foundry. Later, after reading Northern newspaper accounts describing how his men had burned Wrightsville, Gordon fumed at what he called the “base ingratitude of our enemies.”

The black, oily smoke from the bridge fire could be seen for miles. The sight alarmed Early, who, with some staff officers and his headquarters guard, rode out from York to check on Gordon’s progress, later writing that he “had not proceeded far before I saw an immense smoke rising in the direction of the Susquehanna.” Gordon informed him of the skirmish and the burning bridge, the last section of which collapsed some six hours after Frick had ordered it to be torched. Disappointed at his failure to secure the river crossing, Early rode back to York in the darkness.

Grateful for the Georgians’ role in saving the town, Mary Jane Rewalt, the newlywed daughter of Chief Burgess James F. Magee, offered to cook breakfast for Gordon and his staff on the following morning. The Georgian, after establishing his campsite for the evening, retired after a long day to his headquarters near the Detweiler farm.

On Monday morning, Gordon arrived at the Magee house, where Mrs. Rewalt fed him and his officers a tasty breakfast. When Gordon inquired “as to whether her sympathies were with the Northern or Southern side,” she replied, “You and your soldiers last night saved my home from burning, and I was unwilling that you should go away without some token of my appreciation. I must tell you, however, that, with my consent and approval, my husband is a soldier in the Union Army, and my constant prayer to Heaven is that our cause may triumph and the Union be saved.” An admiring Gordon later deemed her “the heroine of the Susquehanna.”

After breakfast, Gordon returned to York and camped along the road to Carlisle. That afternoon, a courier sent by Ewell located Early and informed him that General Lee was concentrating the army and that he was to march his division to Heidlersburg, some 23 miles west of York in Adams County.

June 28, 1863, marked a momentous day in the Gettysburg Campaign. Major General George Gordon Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac after Joseph Hooker resigned. While the bridge was burning at Wrightsville, Confederate spy Henry Thomas Harrison arrived at Lee’s headquarters near Chambersburg, Pa., with news that Meade was now in charge and, more alarmingly, the Union army was closer than Lee believed.

Today, a monument at the intersection of North 3rd Street and Hallam Street (the former Lincoln Highway and York Turnpike) commemorates Wrightsville as the easternmost point that Confederate forces reached during the Gettysburg Campaign, although much of the battlefield has recently been lost to development. Four new Civil War Trails markers help the public visualize what happened on June 28. A new bridge was built on the same piers as the burned structure in 1868, but it was destroyed by a heavy windstorm in 1896. The piers were strengthened and rebuilt, and an iron-and-steel bridge then serviced the river crossing until the Pennsylvania Railroad razed it in the early 1960s. The Veterans Memorial Bridge, completed in 1930 as the longest concrete multiple-arch bridge in the world, now connects Wrightsville and Columbia.

Several hundred yards to the north, the newer Wright’s Ferry Bridge conveys traffic along U.S. Route 30 into Lancaster County. In between, adjacent to the Veterans Memorial Bridge, are the piers of the world’s longest covered bridge, which Union forces sacrificed to prevent Jubal Early from achieving his goal of investing Harrisburg from the rear.