How One Civil War Widow Revolutionized Health Care

“I would not exchange the memory of their grateful faces and their heartfelt ‘God bless yous’ for anything in this world.” —Cordelia Harvey

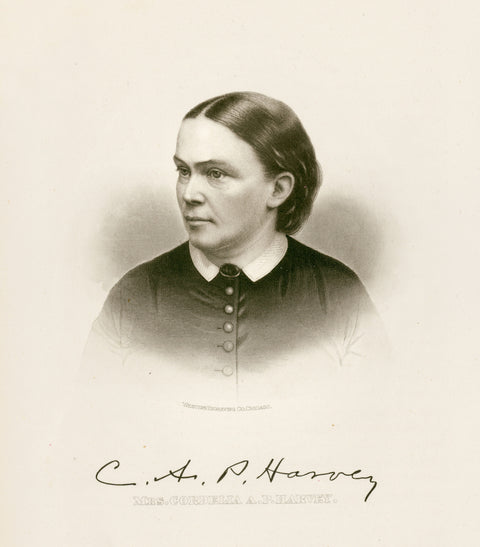

It required tremendous fortitude and self-confidence for a woman in the early 1860s to effect changes that would permanently alter the course of the nation’s health care system and improve the survival rate of soldiers at war. Fortunately, Cordelia Harvey was one such individual.

Born Cordelia Perrine in 1840, she moved with her family from a small community in upstate New York to Wisconsin at the age of 16, settling in Kenosha (then called Southport). There, she began working as a teacher. Seven years later, she wed Louis P. Harvey, editor of Southport’s local newspaper and a young businessman with political aspirations. Cordelia would bear him a daughter, Mary, who unfortunately would soon die of scarlet fever.

In November 1861, with the Civil War in its seventh month, Harvey was elected governor—part of a statewide Republican sweep. He was Wisconsin's seventh governor, and also the first in the state to die in office. Shortly after the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862, Harvey gathered supplies and medical staff, and accompanied them to Tennessee to provide aid to Wisconsin’s sick and wounded soldiers. While attempting to board a steamer on the Tennessee River, he slipped and fell into the water, drowning in the swift current.

During her 94-day tenure as Wisconsin’s first lady, Cordelia had served as president of the Madison Ladies Aid Society, a group formed in support of the war effort. The society supplied Wisconsin troops with everything from handsewn uniforms to pencils and paper for writing letters home. Now, no longer Wisconsin’s first lady, Cordelia was suddenly directionless. Governor Edward Salomon, who had replaced Louis Harvey in Madison, prevailed upon her to take a position as a “sanitary agent” and begin working on behalf of Wisconsin’s wounded soldiers. It was a fortuitous assignment. Expressing genuine concern for the soldiers’ welfare, she began touring various military hospitals in which ill and wounded Wisconsin troops were receiving care. She then made recommendations to Governor Salomon on how that care might be improved.

Early in the war, reliable ambulance and hospital services had yet to be developed out West; in fact, in some areas, medical care was at best rudimentary. Often, soldiers lay upon the battlefield for days before receiving what might pass for aid. The sheer number of sick or wounded so overwhelmed the medical community that neither side was prepared to address the troops’ needs effectively. And of those who did receive treatment, a stunning number would die of infection, shock, or perhaps the greatest killer of all, disease.

Field hospitals were often makeshift affairs set up during or after a battle in local barns, churches, or houses. Proper, or even basic, sanitation was rare. Often, with neither the time nor the expertise to treat and care for battlefield wounds, amputation of limbs was a standard fallback. And given the massive destruction rendered by shell, canister, grapeshot, Minié balls, and so forth, amputation was often justified. Notoriously, severed limbs would be piled up outside overcrowded field tents, where wounded soldiers were frequently lined up in cots or on the bare ground to await treatment. According to many who bore witness, the sights and sounds of a field hospital, as well as the screams and the stench, required a strong stomach for anyone thrust into the midst.

Formal urban hospitals were not much better—often unventilated buildings, converted from schools, hotels, or warehouses. They were stifling in summer, reeked of filth and putrefaction, and were grossly understaffed, undersupplied, and overcrowded. As author Stanley B. Burns attests: “In cities, hospitals were for the indigent and working classes, and had a reputation as places to die. It would not be until the last decade of the nineteenth century that hospitals were looked upon as places of healing.” The prospect, therefore, of proper treatment for a wounded or disabled soldier was unpredictable.

Cordelia Harvey set out to change that scenario. It seemed she was never still, doing whatever she could to secure donations of vital supplies from Wisconsin residents, principally clothing, blankets, and food. A small woman clad in a hooded black cape, she became immediately recognizable on her visits, welcomed for bringing letters, news, and gifts from home. She repeatedly petitioned Salomon for critical supplies and, more important, for additional medical professionals—both doctors and nurses. She would not discriminate between Yankee and Rebel, always willing to visit Confederate prisoners. It wasn’t long before she became known to the troops as the “Wisconsin Angel.”

Harvey used former Wisconsin Governor Leonard

Farwell's Madison residence as a hospital for wounded soldiers during the war.

In 1866, she converted it to a home for soldiers' orphaned children.

(Wisconsin Historical Society)

Two months into her new position, Cordelia met with Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis, commander of the Army of the Southwest, who requested that she oversee the inspection of the hospitals and the care of the troops under his command in the Trans-Mississippi Theater. She was provided with whatever supplies and transportation she requested. That was a prime example of Cordelia’s combined compassion and efficiency in effecting change. In three days alone, she evaluated the condition of 1,500 soldiers, ensuring that those who were too young, too old, or too ill would be sent home.

The terrible pace, combined with the unsanitary conditions in the hospitals that Cordelia visited, took a toll on her health, however. After falling ill in early 1863, she wouldn’t recover for four months, and not until she had returned north. The restorative properties of the fresh Northern air, she was firmly convinced, was what returned her to health.

Cordelia immediately resumed her work, but with a new mission. At the time, Wisconsin did not have its own military hospital, so she circulated a petition for the construction of a facility, for the benefit of the state’s ill and injured troops. She then took the document—which contained some 7,000 signatures, including some of government officials—to Washington, D.C., where she met with President Abraham Lincoln in an effort to get him to open military hospitals throughout the North, specifically the one she desired in Wisconsin. Believing that the ill effects of the dank Southern air—the “Miasma,” as it was called—was having a debilitating and often fatal effect on the troops, she argued to Lincoln: “Many soldiers in our Western army must have Northern air or die.”

Her argument was convincing. The president’s military advisers, however, had convinced him that sending soldiers to hospitals near their Northern homes would induce them to desert. Nevertheless, after three days of meetings, during the course of which she refused to be cowed, she convinced Lincoln—who would describe her as a “lady of intelligence” who “talks sense”—to authorize the establishment of a hospital in Michigan. He offered to name it after her, but she insisted that it bear her husband’s name. In time, two more hospitals would be opened in Wisconsin because of her efforts.

In the summer of 1865, she visited the devastated South and realized that the tremendous mortality rate of the previous four years had left countless children parentless. She convinced the Madison City Council to convert the hospital into an orphan asylum. Over the next several years, hundreds of orphaned children would find a home there. Cordelia served as its first superintendent.

She eventually remarried, moved back east, and returned to teaching. One of her students aptly described her as having “a loving personality—quick, keen and jolly.” Having outlived her second husband as well, Cordelia would return to Wisconsin, where she died in 1895 at age 70. She lies next to Louis and is still remembered throughout the state as the “Wisconsin Angel.”

Ron Soodalter writes from Cold Spring, N.Y.

This article first appeared in America’s Civil War magazine

Facebook @AmericasCivilWar | Twitter @ACWMag