How Civil War Cooks Kept Soldiers Healthy With History’s Worst Vegetables

“Eat your vegetables.”

Parents use the phrase today in a desperate effort to get their children to eat something besides ice cream or french fries. During the Civil War, though, such a request could literally be life-saving.

Disease was responsible for more than two-thirds of all Civil War deaths. Diarrhea and dysentery were the most common reported diseases during the conflict, with more than 1.6 million cases in the Union Army alone. All told, that led to roughly 50,000 deaths on both sides.

Chronic diarrhea was often a sign of malnutrition or critical vitamin deficiencies. In having to deal with it, Civil War doctors and surgeons typically associated diarrhea with scurvy—a disease caused by vitamin C deficiency but one that also was widely acknowledged to be treatable with fresh produce. But why was this such a common problem during the war?

A soldier’s regular diet generally did not include fresh fruits or vegetables, consisting instead largely of salted meat (often pork), beans, coffee, and hardtack (6 parts flour, 1 part water—you can try it at home, though I don’t recommend it). Although there were a few variations in diet for soldiers in both armies (Confederates, for example, typically had cornbread instead of hardtack), the basic nutritional value was the same: poor.

The government had few viable ways of getting vegetables (and the important vitamins that came with them) into a soldier’s diet. Desiccated vegetables became an important tool in the arsenal of nutrition.

In order to combat scurvy among those serving on the frontier before the Civil War, Congress passed a law providing for the creation of canned, compressed, and mixed vegetables: called “desiccated.” The rations of desiccated vegetables supposedly contained string beans, turnips, carrots, beets, and onions that had been compressed into one-inch-by-one-foot rectangular bricks.

Because of the dreadful taste, soldiers would often refuse to eat them. As Sergeant Cyrus Boyd of the 15th Iowa grumbled: “I ate a lot of dessicated vegetables yesterday and they made me the sickest of my life. I shall never want any more such fodder.” It wasn’t long before the troops branded the creation “desecrated vegetables.”

Nevertheless, these were indeed vegetables in the cans. Soldiers, however, were instructed to prepare them in a soup that would take 1–3 hours to prepare, which likely diminished the health benefits. Not only were many vitamins boiled out of the vegetables, but the lengthy preparation time also made it hopelessly impractical to prepare while an army was on the move.

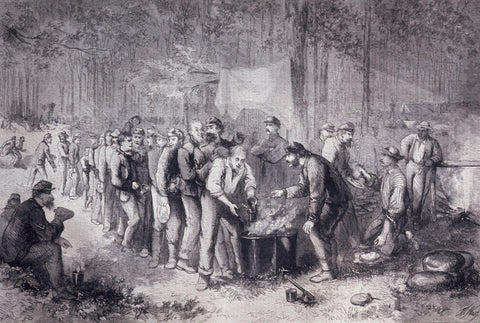

Foraging (even when it was not allowed) was an important, if sporadic, means for soldiers to access fresh fruits and vegetables. It was not uncommon for soldiers to seek out fruits or vegetables as they passed or camped by local farms. In at least one recorded instance, General Robert E. Lee encouraged his men to forage the surrounding countryside in the weeks leading up to a campaign so they would be in peak health.

Civil War medical personnel were well aware how critical fruits and vegetables were for healthy armies, particularly, as mentioned earlier, in cases of scurvy. The fruit-and-vegetable option to treat diarrhea was less common, but doctors frequently went that route if cases lingered for extended periods.

In 1863, Union surgeon Joseph Woodward concluded in a study on camp diseases that Civil War surgeons, though often stereotyped as ill-informed butchers, could form fairly sophisticated hypotheses based on data they collected. Woodward’s understanding of chronic diarrhea and its causes was strikingly accurate:

Originating chiefly among troops in camps, [diarrhea] evidently stands in some definite relationship to the usual conditions of camp life. Of these, it would appear most intimately connected with the diet, and this relationship is of such a kind that chronic diarrhea becomes more and more common and fatal as the constitutional manifestations which result from camp diet approach more and more to the condition of recognizable scurvy, a most important point to be considered in connection with the hygienic treatment of this disease. As a consequence it has more than once happened on a grand scale, during the present war, to see a sudden and palpable diminution in the amount of diarrhea follow the liberal issue of potatoes and onions to an army in which the tendency to scurvy was exhibiting itself in a manner too evident to be overlooked.

Lack of fresh produce usually hindered fulfillment of recommended dietary treatments. To increase that supply, the federal government often relied on the aid of private organizations like the U.S. Sanitary Commission.

This article first appeared in America’s Civil War magazine

Facebook @AmericasCivilWar | Twitter @ACWMag

Thankfully civilians appreciated the benefits of eating healthy. Getting vegetables to the frontlines was as important as medicine and bandages, according to the Sanitary Commission, which occasionally held fundraisers to pay for shipping those essential vegetables. One campaign slogan perfectly captured the sentiment: “Don’t send your sweetheart a love letter. Send him an onion.”

Shipping vegetables to the troops became an important task for the Sanitary Commission. A lack of potatoes and onions nearly produced a health epidemic for Ulysses Grant’s army in the 1862-63 Vicksburg Campaign. Upon hearing this, Mary Livermore of the Western Sanitary Commission (a separate but related entity) resolved to marshal their resources to alleviate the dire shortage. Once they accumulated the necessary vegetables, they had to find a way to get them to the front since the roads were in such poor condition. Eventually, Livermore convinced Grant to provide boats to ship the produce if the women of aid societies would make sure the boats were manned. Thus, the “potato fleet” was born.

In the end, eating one’s vegetables was the most effective way to avoid the deadliest condition of the war—diarrhea. It could be fairly stated then that if the soldiers had been able to eat more vegetables, Civil War armies would have been larger, healthier, and more prepared to fight—and their mothers would have been happy.

John Lustrea is the Director of Education and the Website Manager at theNational Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park during the summers of 2013-16.