Her Great-uncle Died on D-day. We Found out What Happened

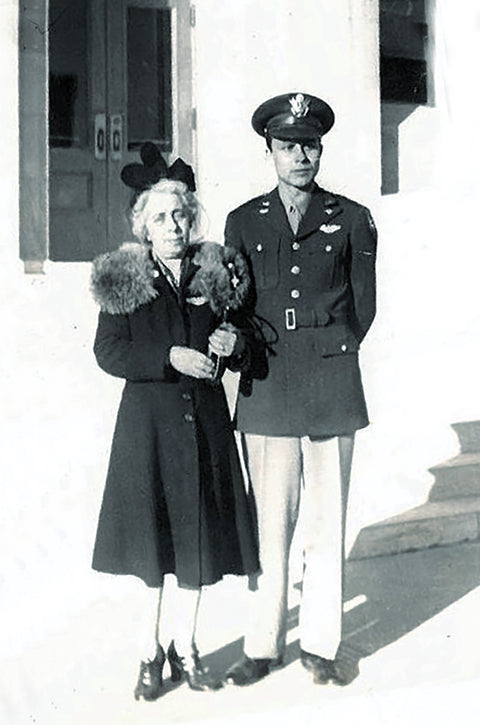

My great-uncle, Captain Everal Anthony Guimond, was a bombardier in the 566th Bombardment Squadron, 389th Bombardment Group, Heavy, of the U.S. Army Air Forces. He was killed on D-Day and his military records were destroyed in the 1973 St. Louis Archives fire. What can you tell me about my great-uncle’s service and his unit’s history?

—Laura Guimond, Henderson, Nevada

The 566th was one of the four original squadrons of the 389th Bombardment Group of the Eighth Air Force, whose B-17 and B-24 bombers famously took the air war to Germany.

Constituted on December 19, 1942, the 389th was activated a week later at Davis-Monthan Air Field in Arizona before moving to Biggs Field, Texas, and Lowry Field, Colorado. Between mid-April and June 1, 1943, the 389th received final flight training at Lowry on the Consolidated B-24 Liberators they would fly throughout the war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt formally reviewed the unit at Lowry during a late-April visit, an event the Rocky Mountain News wrote was “believed to be the sole occasion when a USAAF bomb group was so honored.”

The 389th’s ground echelon left Colorado on June 5 for the Camp Kilmer staging base in New Jersey. Three weeks later the unit joined 17,000 other troops on the Cunard ship RMS Queen Elizabeth to sail to England . Along with the thousands of other Americans servicemen, on board was the famed CBS radio commentator Edward R. Murrow, who gave airmen an idea of what sort of life awaited them at a USAAF air base in England. The unit arrived at their new home base at RAF Hethel, in Norfolk, England, in mid-June. The air echelon left Lowry on June 21, hopscotching across the U.S. before making transatlantic flights to Prestwick, Scotland. The B-24s then convoyed south to join the rest of the 389th at Hethel.

A B-24 of the 389th bombs

occupied St. Malo, France.

Under the command of Colonel Jack W. Wood, the 389th settled into its new digs. The group’s airmen were soon perplexed when, after having trained in the U.S. for standard high-altitude bombing missions, their training in England suddenly turned exclusively to low-altitude runs. As Lieutenant Andrew Opsata of the 93rd Bomb Group said regarding the Americans’ buzzing of the English countryside, “We terrorized the livestock, and I’m certain that egg and milk production must have taken a precipitous drop.” What the American airmen didn’t know was that they were preparing for the top-secret Operation Tidal Wave, the planned attack on Nazi Germany’s oil refineries in Ploesti, Romania. Since the B-24s couldn’t reach Ploesti from England, on July 1, 1943, the 389th departed to join the 44th and 93rd Bomb Groups of the Ninth Air Force in Benghazi, Libya. Low-level flight training continued there amid the stifling desert heat and a plague of locusts and flies numbering in the millions. Another local troublemaker inspired the 389th to adopt the nickname that would serve them until the end of the war: the Sky Scorpions. From Benghazi, the 389th flew their first missions from July 9-19, attacking Axis airfields on Crete and as well as targets in support of Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. The group flew additional missions from Libya against ports and rail yards in Italy and Austria, but the big event was August 1, 1943—the attack on Ploesti.

The mission launched at 4:00 a.m., when 179 B-24s headed north from Benghazi over Corfu and northeast to Romania. The 566th Squadron’s target was Campina, the most distant of the refineries, as their B-24s were the latest models and had the longest range of the air groups. While the refineries took their hits, so too did the attackers. Of the 179 airplanes that took off, 43 planes were shot down, 532 men died, and 110 men survived bail outs to become POWs. Despite these sobering figures, the Ploesti raid succeeded in damaging the refineries and disrupting—temporarily, at least—the German war machine. The Sky Scorpions received a Distinguished Unit Citation for their efforts that day.

The 389th returned to England on August 25 and soon began a 21-month slog to bomb the Germans into submission. Meanwhile, the crews settled into everyday life at Hethel. A joint 389th/RAF rugby team played a full season of matches, and the airmen joined the war-long chorus railing against the Spam, powdered eggs, and chipped beef that seemed omnipresent in the chow lines. On Christmas of 1943, the 389th received a visit from an old friend: Edward R. Murrow dropped by to conduct interviews for his radio report home to the U.S. and ended up having his Christmas meal with Hethel’s enlisted men.

From August 1943 until the end of the war, the group flew hundreds of missions against airfields, marshaling yards, V-1 rocket sites, and numerous other targets in occupied Europe and Germany. In February 1944, the 389th was at the forefront of Big Week, the Allies’ intense bombing campaign against the ball- bearing, engine, and aircraft factories of the German aviation industry. The overall effort was not as successful as at first thought or hoped, but it was another strike in the war of attrition against Germany. But it was a war of attrition for both sides—Allied losses from German fighters and 88mm flak batteries were painfully significant.

Your great-uncle, Captain Everal Guimond, enlisted in the U.S. Army on April 4, 1942, and traveled to England with the rest of the 389th in June1943. A bombardier on Lieutenant Gregory Perron’s crew for 10 missions starting in November 1943, Captain Guimond transferred to a B-24 commanded by Lieutenant William Wambold in February 1944. His first run with the new crew was a bombing mission over Braunschweig, Germany, on February 20, the first day of Big Week.

On April 1, 1944, USAAF brass raised from 25 to 30 the number of missions required for airmen to complete their tour. A sliding scale was put in place, so your great-uncle’s tour was scheduled to end after 29 missions. As D-Day approached, Captain Guimond’s tally stood at 28. Tragically, his final mission, on D-Day, would have been the last of his tour.

On June 6, the Liberators of the 389th flew numerous bombing missions in support of the Normandy landings. Captain Guimond was assigned to replace the regular bombardier on a B-24J-4 called Shoot Fritz, You’ve Had It under the command of Lieutenant Marcus Courtney. Taking off from Hethel at 2:00 a.m., the airplane, for reasons that were never determined, crashed and exploded 20 minutes later near the village of Trimingham on the Norfolk coast. All ten crewmembers perished.

The 389th continued to punish the German rail system, submarine pens, and shipping yards as the Allied invasion pushed on. The Sky Scorpions flew numerous missions during Operation Market Garden in September 1944—though the weather was so bad during the Battle of the Bulge that the group was unable to provide much material help. In February and March 1945, bombers switched from dropping explosives to airdropping food and other needed supplies to the advancing Allied armies. Their final mission, the last of 321 before the war in Europe ended in May, came over Germany on April 25. The 389th returned to the United States in late May and the unit was deactivated on September 13, 1945.

Everal Anthony Guimond was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster, the Air Medal with 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, and the Purple Heart, and he is buried in Plot E, Row 5, Grave 16 in England’s Cambridge American Cemetery. Your great-uncle’s service and sacrifice are also remembered at the National D-Day Memorial in Bedford, Virginia, where his name is enshrined on the Wall of Remembrance. Captain Guimond’s plaque, number W-99, resides next to those of 4,414 other servicemen who gave their lives on June 6, 1944, day one of the liberation of Europe.