He Was a Fast-Rising Judge in Arkansas. He Ended His Career in Disgrace.

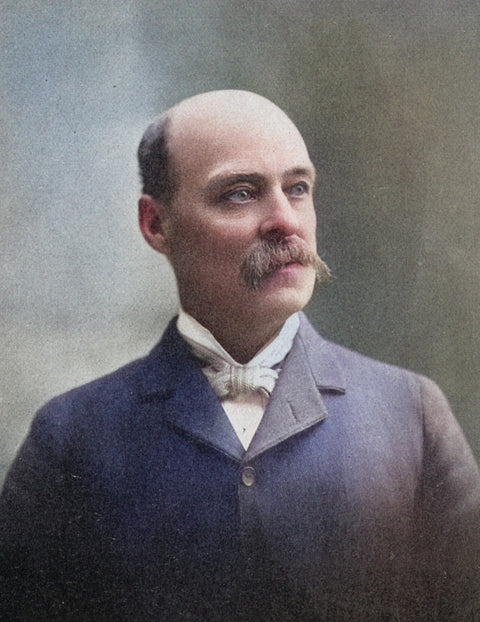

When former federal judge and Colorado lieutenant governor William Story died in 1921, newspaper obituaries glossed over the most turbulent episode of his career. In 1874, under threat of impeachment, he had resigned as judge of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas. Before the court garnered headlines as the jurisdiction of Isaac “Hanging Judge” Parker and Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves, it was the domain of Story, a man considered by many contemporaries the most corrupt judge in the West.

On March 3, 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant nominated Story and Congress confirmed him to the bench of the new district court, which operated out of Fort Smith and was responsible for all federal legal matters occurring within its approximately 75,000-square-mile jurisdiction, from western Arkansas into Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). While Congress had split Arkansas into two federal districts in 1851, successive judges had presided over both until Story took the helm of the Western District.

The court struggled with the racial strife of Reconstruction and grappled with frontier lawlessness amid disputes over Indian sovereignty and white settlement. It dispatched marshals into Indian Territory to arrest and bring to trial individuals accused of crimes. Yet so vast was the district, it could take days, weeks, sometimes months for lawmen to scour the boundaries of the territory and return with fugitives in tow. Complicating matters was the recurring question of jurisdiction—whether a suspect should be tried in an Indian court (of which there were several) or Story’s federal district court.

It was a plum assignment for Story, though newspapers in his home state of Wisconsin expressed doubts about the readiness of its young native. “That boy grew up without any particular aim in life, read law a short time in Milwaukee, provided himself with a carpet bag and went to Arkansas,” The Oshkosh Times wrote rather uncharitably. Though it deemed him “not very promising,” the paper said his family connections gave him “some degree of eminence.”

Arkansas Governor Isaac Murphy appointed Story as a

judge in the state’s Eighth Judicial Circuit, in the southwest part of the

state.

Born in Waukesha County on April 4, 1843, Story earned a law degree from the University of Michigan in 1864. He may have been encouraged in his career choice by the memory of his paternal great uncle Joseph Story, who’d been an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. After serving in the Union Army during the Civil War, young Story practiced law in Wisconsin and Arkansas. In 1867 Governor Isaac Murphy of Arkansas appointed him as a judge in the state’s Eighth Judicial Circuit, in the southwest part of the state. Soon after taking office in 1869, Republican Governor Powell Clayton appointed Story to the bench of the Second Judicial Circuit, in northeastern Arkansas. “The youngest judge of the grade in America is William Story, of the Arkansas court,” Wisconsin’s Janesville Daily Gazette trumpeted on Jan. 26, 1869. “He is 25 years old.”

Two years later came his appointment to the Western District, a plum position paying $6,000 a year, a hefty sum at the time. Taking up residence at the Metropolitan Hotel in Little Rock, 28-year-old Story went to work, hiring commissioners and marshals, and the papers soon reported he had his court up in “apple pie order” and running like “well-oiled machinery.” Within a few months of his arrival, however, he fell dangerously ill. On June 17, 1871, the jurist overdosed on chloroform he’d reportedly purchased and taken by mistake to alleviate a headache. It took a doctor several hours to revive him, and Story several days to fully recover. It was a harbinger of trouble to come.

Actively involved in Republican politics, Story had supported Arkansas’ First District congressman Logan H. Roots in the latter’s unsuccessful 1870 campaign for re-election. Roots had supported Story’s appointment to the bench, so the judge softened the blow of Roots’ defeat by hiring him as marshal of the Western District. Story also hired, as commissioners, two other men with whom he was politically aligned. Little more than a year after he took the bench, however, the U.S. attorney forced out Roots as marshal amid reports of fraud and soaring expenses. One rival newspaper claimed the marshal, with Story’s tacit approval, had dispatched deputies to round up sympathetic townsmen to vote for certain candidates in a local election. Meanwhile, local attorneys complained about Story’s two hired commissioners, accusing them of having withheld payments to witnesses who had often traveled hundreds of miles to appear in court, forcing some to sell personal effects to pay their expenses.

When Governor Powell Clayton took office in 1869, he

appointed Story to the bench of the Second Judicial Circuit, in northeastern

Arkansas.

Story himself allowed marshals to charge the federal government for work they apparently never did, raising the question of whether he was getting kickbacks. “Parties who never left town,” Little Rock’s Daily Arkansas Gazette reported, “were allowed and paid full fees of all kinds for hunting after prisoners, and some parties were allowed [and paid] for arrests made at a distance, when they did not leave town or make any arrests.” Moreover, the paper alleged, Story signed blank vouchers and let marshals charge whatever they chose, without submitting proper receipts, a practice that cost taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars. Worse still, cases listed on some vouchers were fabrications. The attorneys also questioned Story’s handling of certain cases, particularly his decision to allow the release of one convicted murderer on bail before sentencing—a man who was neither pursued nor retried.

According to Story’s biographer, it was a May 1873 bribery charge that sealed his fate. The charge accused the judge of having accepted $2,500 to dismiss an indictment against an Indian Territory druggist for having illegally sold liquor to Indians. A U.S. attorney was accused of having accepted a $500 bribe to further guarantee a dismissal in the case. Such accusations continued to swirl around Story and his court until finally, in early 1874, Congress started a formal investigation. It ultimately charged him with 19 counts of corruption, notably the sale of his office for favors. Story appeared before the U.S. House Judiciary Committee, which found his explanations for such alleged transgressions “lame, disconnected and unsatisfactory.”

Rather than face impeachment, Story resigned, on June 17, 1874. President Grant appointed Judge Parker in his place and tasked the “Hanging Judge” with reforming the federal court for the Western District. Story moved his family to Ouray, Colo., where, despite the recent allegations of corruption, he built a successful law practice. In 1891, after a move to Denver, he was elected Colorado’s lieutenant governor. In 1913 he relocated to Salt Lake City, where he resumed private law practice. Story eventually retired to Los Angeles, dying there at age 78 on June 20, 1921.