Fistfights, Heat Exhaustion, and Not Enough Taters: What It Was Like at Gettysburg’s 50th Reunion

The common story of the 1913 reunion of the Blue and Gray at Gettysburg emphasizes camaraderie between former foes and the shared reminiscences of past glories. More than 50,000 elderly veterans showed up, creating the biggest tent encampment on American soil since the Civil War. The national press covered the four-day event in exhaustive detail, and President Woodrow Wilson gave his own “Gettysburg Address” that, while not quite on a par with Lincoln’s, was still widely praised.

There was another side to the reunion that has been lost amid all the nostalgia and patriotism attached to the event, however. One of heat, chow shortages, and short tempers. Some of those reports have come to light only recently thanks to the online digitization of newspaper archives. Reporters did not have recording devices or readily available databases for fact-checking. They were reliant on memory and notes to write their stories. That is why names were spelled differently in various reports and some men could get away with telling whoppers about their age and wartime service.

Veterans came from 46 of the 48 states (minus only Nevada and Wyoming). Those who came from the Far West spent four days or more on trains to get to Gettysburg, a town served by just one rail line. Some of the aging men had argued for a Gettysburg reunion ever since the last one 25 years earlier in 1888. While there were still enough of them around to hold a reunion, they lobbied for another grand get-together. Not all, however, were in favor. Seventy-seven-year-old R.M. Holbert of Fort Worth, Texas, who had fought under the Stars and Bars remained an unreconstructed Rebel. “I gave those Yankees all that was a-comin’ to ’em in the sixties,” he said, “and it is certain I’m not goin’ to fool ’round ’em now.” Besides, he added, “Gettysburg is too far north of the Mason-Dixon line.” On the other extreme was an 85-year-old veteran who lived with his son. The son told the old man he could not go “under any circumstances,” so the vet crawled out a window and went anyway. Who could be neutral about something so important to their lives?

Newspapers in countless little towns across the country followed the preparations of the veterans who planned to go. Some of the men whom nobody had paid attention to for years were suddenly celebrities and interviewed by every reporter who could get them to sit down. The resulting stories were sometimes long on derring-do and short on facts, reflecting the passage of the years and the desire to please. Judge Charles C. Cummings of Fort Worth, who considered himself something of a historian, recounted how as a member of the 7th Mississippi Infantry he had been wounded on the first day of the battle. But as he went on, he came off better than Maj. Gen. George Pickett, who in his version lost a leg in the charge bearing his name and “died as a result of his injury” soon thereafter. Pickett actually died in 1875—with two good legs.

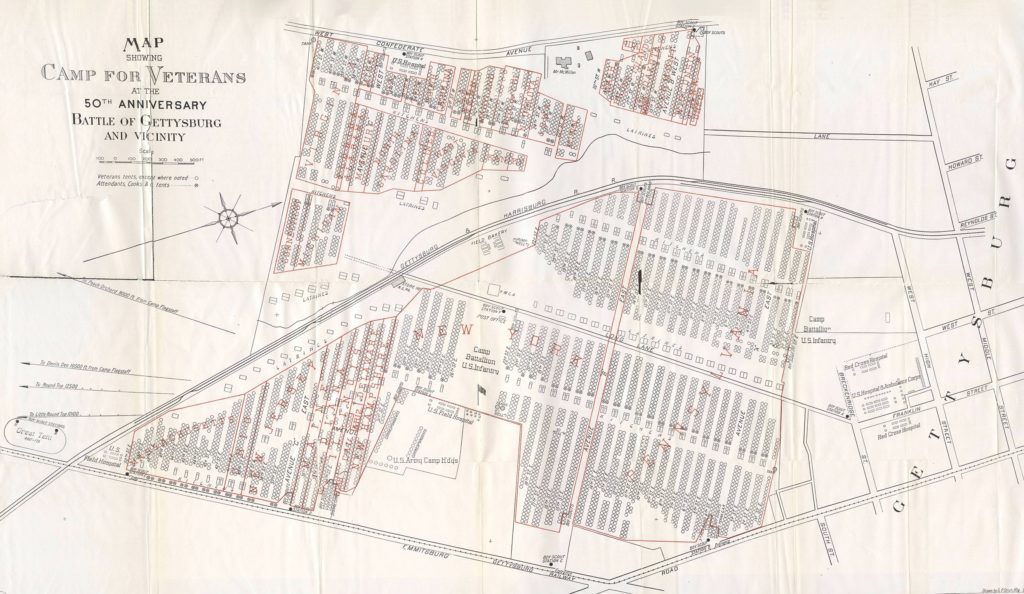

The reunion was hosted by the U.S. Army, the Gettysburg Battlefield Commission, and the town of Gettysburg itself. Except for those who might have friends in the town or managed to secure a room in the Gettysburg Hotel, everybody got the same accommodations: U.S. Army tents, courtesy of the Philadelphia Supply Depot. Their occupants included officers and privates alike. The tents were laid out in street after street covering several hundred acres. Some of the old vets got lost at night trying to find their street. The Army also set up mess tents, rest stations, hospitals, and telephone lines for an expected crowd of 40 to 50 thousand. All their planning and preparation, however, were overwhelmed by the 55,000 veterans and 10,000 visitors who showed up. The Battlefield Commission put together the program and raised money, and the town threw open its doors symbolically speaking.

But the town’s hospitality extended only so far. They prohibited the sale of alcohol, so the elderly gents had to make do with what they had brought with them or send out to other nearby towns, a little foraging reminiscent of the old days. The spirit of camaraderie included former rivals sharing a bottle in get-togethers at night, resulting in “many cases” of “overindulgence in alcohol” being treated in the local hospital.

The Blue and Gray did not just meet at Gettysburg. Many former enemies traveled together, sometimes for several days. They were already acquainted with each other back in their hometowns and had worked together before. For instance, on Decoration Day (Memorial Day) every year, United Confederate Veteran (UCV) camps and Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) posts in the former Confederate states held joint ceremonies while decorating the veterans’ graves in the local cemeteries, albeit with different flags. Now they collaborated in raising the money to attend the reunion.

Many of the elderly gents, living on piddling pensions and the charity of family members, could not afford such a trip on their own. Together Blue and Gray launched fund-raising drives. In Fort Worth, for instance, the members of the R.E. Lee Camp of the UCV and the William S. Parmley Post of the G.A.R. formed a joint committee they called the “Blue and Gray Committee” to raise money and plan the trip. They arranged with the St. Louis and Southwestern Railway (aka the “Cotton Belt”) for their very own car to take them at the bargain rate of $39.40 per person round-trip, reservations required.

At one point 80 veterans were said to be making the trip from Fort Worth, but when the day arrived only five had actually purchased tickets. Their numbers swelled to 20 as they were joined by men from as far away as Houston. Their most distinguished traveling companion was former Confederate General Felix H. Robertson, the Texas representative on the Gettysburg Battlefield Commission who had already spent time on site preparing for the big event. Now he was back in Texas to lead the Texas contingent.

The intrepid travelers set out on their journey on June 26 at 8:50 p.m. They picked up additional veterans as they crossed Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri, and on the way shared liquid refreshment they had brought on board to ease their aching bones and pass the time more pleasantly. Thanks to the Cotton Belt’s arrangements they did not have to change cars even once all the way across five states.

They arrived hale and hearty at Gettysburg’s little train depot on the night of June 30 only to discover there was a shortage of tents. They had to sleep on the ground under the stars that night but took the foul-up in good nature, recalling similar sleeping arrangements 50 years before. At least they did not have to eat hardtack, and no one would be shooting at them the next day. Some of the men preferred to sleep outside, at least until a deluge hit on July 2. There were separate encampments for Blue and Gray, but many veterans spent their time visiting the other side’s tents.

To accommodate the additional thousands, the Army had to scramble, even borrowing circus tents and packing in the assigned occupants. Still, there were not enough tents on hand, and shipping in more from St. Louis would have taken too long. So hundreds slept on the ground, willingly or otherwise. The chief complaint about the Army-served chow was not the quality of the food but the meager amounts they got at every meal. Most of them had not gone hungry since the end of the war, and now they were reliving another unpleasant aspect of soldiering that they thought they had put behind them.

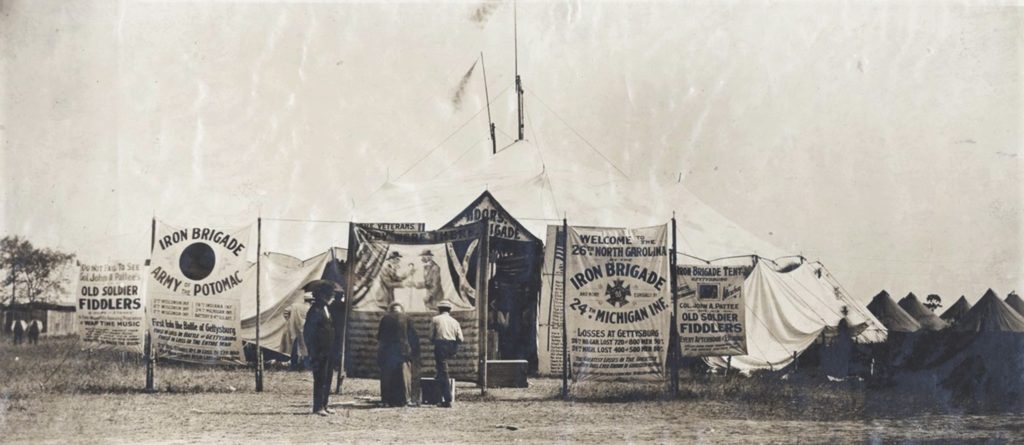

There were gestures of kindness over and above the common courtesies. Colonel Charles McConnell, a 24th Michigan color bearer at Gettysburg, brought from Chicago a large tent to serve as the headquarters for his old regiment. Once it was set up, however, he invited the survivors of James Pettigrew’s North Carolina brigade to join them. The two regiments had fought each other on July 1, 1863; now they would gather under the same tent as brothers in arms. It was also the only tent on the whole field not furnished by the U.S. Army.

Aside from accommodations and food, the biggest problem was the brutal July heat. The temperature reached 90˚ F. outside on the second day, reaching 103˚ indoors with no such thing as air conditioning. The forecast was that it would go higher before it was time to leave. Those temperatures were similar to what they had been in 1863, but these were no longer young men hardened by campaigning. Hundreds would suffer heat prostration and wind up in the hospital tents over the course of the four days. On July 2, General Hunter Leggett, the U.S. Army officer in charge, told a reporter that 6,000 men had already departed, and he estimated another 1,000 leaving that night. He tried to put the best face on it by explaining that the old fellows had gotten what they came for: a chance to see the old battlefield one more time, shake hands with long-ago foes, and reconnect with comrades. Having done all that, they were ready to return home and sleep in their own beds and eat home cooking. On July 2, a storm blew through that replaced sweltering temperatures with soaked clothing.

Getting around the battlefield, which had not changed much since 1863, was a challenge for the aged veterans. While some made pilgrimages to Devil’s Den or Culp’s Hill, most were not so energetic. They stayed in the shade and hydrated with one form of liquid refreshment or another. Most of the socializing that went on was at night after the sun went down and the day’s heat had dissipated. Some Union vets organized an impromptu fife and drum corps and went calling on their Confederate comrades.

The old fellows were not much interested in the first day’s fighting. Instead, they wanted to visit the sites and recount the stories of the second and third days. That was true of both sides. Judging by the reports, a remarkable number of the Confederates in attendance took part in Pickett’s Charge, or at least that was the way they remembered it. Fifty-year-old memories could get blurred. Two veterans, one Union and the other Confederate, met at Devil’s Den. The Confederate found the spot where he had been wounded on the second day and recalled that a Yank had saved his life by giving him water. The Union veteran cried out that he was that Yank.

The problem with the touching story is that the Johnny Reb had been a member of Garnett’s Brigade, and they didn’t fight at Devil’s Den. Reporters wrote down the stories they heard without attempting to verify their authenticity, sometimes acknowledging that some stories may have been the result of “fifty years of embellishment.” According to veterans of both sides, there had been hard hand-to-hand fighting on all three days, at places with memorable names: Barlow’s Knoll, Culp’s Hill, Devil’s Den, the Peach Orchard, Little Round Top, the Bloody Angle.

The oldest veteran at the reunion was Micyah Weiss, a Union vet who said he was either 110 or 112 years old (the story changed) and who also happened to be a veteran of the Mexican War (1846-48). If true he was a freak of nature. He said he had enlisted with the 144th Pennsylvania at the advanced age of 55, meaning he was older than most of the senior officers in his second war. No one at Gettysburg in 1913 asked for a birth certificate, and his stories of service in two wars entertained his fellows for four days. The youngest was 61-year-old John Clem who said he had been a Union drummer boy in 1863, but his story, too, was subsequently questioned.

Distinguished attendees included the governors of six states (Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Virginia, Kentucky, North Dakota, and Iowa). Texas Governor Oscar Colquitt considered coming, and as late as June 25, newspapers reported he was going. But at the last minute he decided not to go, instead naming General Robertson, the state’s only native-born Civil War general to represent Texas. For those with long memories, Robertson was the same officer who had been disgraced by the actions of his troops in the Saltville Massacre (October 2, 1864) to the point that General Lee called for his court martial.

But all was forgiven now. Robertson was in Gettysburg on May 21 when Gettysburg officially welcomed the Battlefield Commission. He delivered the opening speech, receiving a “tremendous ovation” from the assembled townspeople and making him the first Southerner ever to speak as the Pennsylvania town’s representative at a public event. Now he was back and leading the Texas contingent of veterans.

The Gettysburg experience was a dream come true for Robertson. In the spirit of forgive and forget his checkered past was not brought up. He was feted by Yanks and Johnny Rebs alike. For four days he strutted about the town in his general’s uniform, which was spotless and fit surprisingly well for something that had been in the closet for 50 years. One of the warm, fuzzy anecdotes to come out of the reunion involved Robertson on the last night. As related by him later, he chanced to meet a former West Point classmate who fought on the other side, General Barlow (presumably Francis Barlow, the one Union general by that name).

Both in his telling were members of the class of 1857, and now they were seeing each other for the first time since 1861. The Texan recognized Barlow first and introduced himself, and they spent several hours in Barlow’s tent reminiscing about West Point and their wartime experiences. Nobody back in Texas questioned the story, but it had a few problems, beginning with the fact that Francis Barlow died in 1896. He also never attended West Point. Robertson entered West Point in 1857, but he would have been a member of the Class of 1861, not 1857, had he graduated, but he left in January 1861 to join the Confederacy. A lot of stories also of dubious authenticity were perpetrated at Gettysburg during those four days of 1913. Reputations were burnished after the fact, careers rewritten, and memories created out of whole cloth. Among Texans, however, Felix Robertson, last surviving general officer of the Confederacy (he died in 1928), would always be a hero.

Neither the old warhorse Felix Robertson nor the attending governors were the biggest celebrities at the reunion. That honor went to the descendants of beloved general officers, a select group that included a son and two grandsons of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, A.P. Hill’s daughter, two grandsons of General George Pickett, and three granddaughters of General George Gordon Meade.

The grand reunion of Blue and Gray wrapped up on July 4 with a series of speeches climaxed by President Woodrow Wilson’s speech. Then it was home for the old fellows. The “after-action” report on the event said there were only nine fatalities during the four days, eight Union men and one Confederate. One newspaper reported that one of those deaths was the result of being struck by a car.

It is impossible to know exactly how many attended. The count of Lewis Beitler who compiled the Report of the Pennsylvania Commission was 53,407, but that number blurs the fact that thousands departed before it was over. Various newspaper reporters on the scene also offered different counts. How to count them? No one could know for sure how many were there.

The theme of “unity of North and South,” was endlessly repeated afterwards. It was symbolized by the meeting of the survivors of Pickett’s Charge, Billy Yank and Johnny Reb, at the stone wall on July 3, exactly 50 years after they clashed there in a death struggle. Now the one-time foes shook hands across the wall. (The latter may have been true, but the former was open to question.)

Contrary to later reports, all was not peace and love between the old gents. A mixed group got into it in the dining room of the Gettysburg Hotel on July 2 when a Union vet defended Abraham Lincoln against the jibes of Southerners. Seven men were stabbed, all of them Yanks. The victims were all lightly injured, and their assailant was released.

Fort Worth Judge Charles C. Cummings was not shy about partisan feelings in his speech on the last day of the reunion. Said he proudly, “The South has risen again,” not as some sort of “New South” but as “the same Old South!” Buried in the middle of his speech, this statement drew no response from the crowd.

Among all the half-truths and tall tales to come out of the reunion was one myth that has taken on added significance in recent years, namely that the Gettysburg event did nothing to honor the nurses who attended the thousands of wounded in 1863. But they were certainly honored in 1913. Mrs. Salome M. Stewart, a resident of the town, turned her house “on a quiet little street” into a headquarters for the nurses of both sides. During the battle it had been an emergency hospital for the wounded of both sides run by Mrs. Stewart and six like-minded women of the town.

With word of the reunion spread across the country, the nurses came back to Gettysburg from as far away as New York, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin. Some of the veterans of both sides who had been under their tender ministrations came by to see them. Even reporters dropped by to see why all the attention on these gray-haired ladies and hopefully get a fresh human-interest angle on the reunion. So, no, those women were hardly forgotten.

The warm afterglow of the Grand Reunion stayed with attendees long after they bid farewell to Gettysburg. Judge Cummings pronounced it, “the grandest occasion of the century,” adding, “The spectacle of 50,000 men who formerly fought each other fraternizing will never be seen again.” Perhaps the most remarkable thing to come out of it was the proposal that Confederate and Union veterans’ organizations merge into one known as the United American Veterans. But nothing came of it. An occasional reunion with their opposite numbers was okay, but subsuming their unique identities into some integrated organization was too much.

One person who did not attend the reunion was Sallie Pickett, aka LaSalle Corbell Pickett. Major General George E. Pickett’s widow, 70 years old, was still mourning the death of her son, George Jr., two years earlier. As she wrote a friend: “Oh, I would like so much to be there, but do not feel that I would be able to bear up under the flood of emotions memory would arouse. My husband is dead, my son is dead, and it would be best for me not to attend.”

Her health was also not up to the trip from her home in Washington, D.C. So, she sent her two grandsons, George III and Christiancy Pickett, to represent the family. They were the center of attention for all the Virginia veterans who had hoped “Mother Pickett” would attend the reunion as she had in 1888.

The Pickett boys, 19 and 17 respectively, brought their grandmother’s warm wishes and posed for pictures. Veterans presented them with a special gift for Sallie. It was a gold pocket watch engraved to “Mrs. Genl. George E. Pickett.” The message on the back said everything about their high regard for the general and his lady. Engraved in tiny print letters, all caps, to her was this inscription:

“…by Pickett’s men in memory not only of our beloved general but her own loyalty to us his soldiers. July 3rd 1913.”

Sallie cherished the reunion watch until her death in 1931, as well as a watch engraved with George’s battles, which she had given him as an anniversary gift. She considered herself George’s spokesman to his men. They in turn revered her. —R.S.