Cuban Missile Crisis: How Close America Came to Nuclear War with Russia

It was one minute before high noon on Oct. 27, 1962, the day that later became known as “Black Saturday.” More than 100,000 American troops were preparing to invade Cuba to topple Fidel Castro’s communist regime and destroy dozens of Soviet intermediate- and medium-range ballistic missiles thought to be aimed at targets in the United States. American reconnaissance aircraft were drawing enemy fire. The U.S. Strategic Air Command’s missiles and manned bombers had been ordered to DEFCON-2, one step short of nuclear war. In the Caribbean, U.S. Navy destroyers were playing a cat-and-mouse game with Russian submarines armed with nuclear-tipped torpedoes.

And then, at 11:59 a.m., a U-2 spy plane piloted by Captain Charles W. Maultsby unwittingly penetrated Soviet airspace in a desolate region of the Chukot Peninsula opposite Alaska. Flying at an altitude of 70,000 feet, the 11-year Air Force veteran was oblivious to the drama below. He had been on a routine mission to the North Pole, gathering radioactive air samples from a Soviet nuclear test. Dazzled by the aurora borealis, he’d wandered off course, ending up over the Soviet Union on the most perilous day of the Cold War. He was completely unaware the Soviets had scrambled MiG fighters to intercept him, and not until he heard balalaika music over his radio did he finally figure out where he was.

A former member of the Air Force’s Thunderbirds flight-demonstration team, Maultsby had enough fuel in his tank for nine hours and 40 minutes of flight. That was sufficient for a 4,000-mile round trip between Fairbanks’ Eielson Air Force Base and the North Pole, but not enough for a 1,000-mile detour over Siberia. At 1:28 p.m. Washington time, Maultsby shut down his single Pratt & Whitney J57 engine and entrusted his fate to his U-2’s extraordinary gliding capabilities. The Air Force’s Alaskan Air Command sent up two F-102 fighters to guide him back across the Bering Strait and prevent any penetration of American airspace by the Russian MiGs. Because of the heightened alert, the F-102s were armed with nuclear-tipped air-to-air missiles, sufficient firepower to destroy an entire fleet of incoming Soviet bombers.

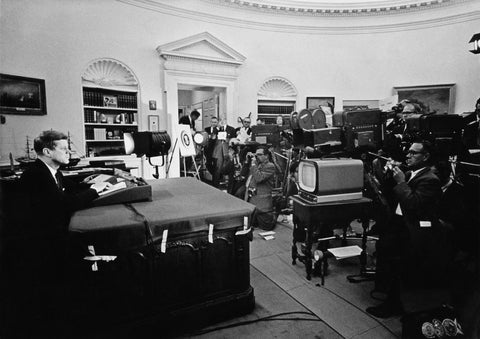

On the ground, SAC commanders were frantically trying to retrieve their wayward reconnaissance plane. They knew Maultsby’s location, as they had tapped into the Soviet air-defense tracking network. But there was little they could do with this information: The ability to “read the mail” of Russian air defenses was a closely guarded Cold War secret. Pentagon records show that Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was not informed about the missing U-2 until 1:41 p.m., 101 minutes after Maultsby first penetrated Soviet airspace. He briefed President John F. Kennedy by phone four minutes later.

“There’s always some sonofabitch who doesn’t get the word,” was Kennedy’s frustrated response.

At 2:03 p.m. came news that another U-2, piloted by Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., was missing while on an intelligence-gathering mission over eastern Cuba. Evidence soon emerged it had been shot down by a Russian surface-to-air missile near the town of Banes. Anderson was presumed dead.

Historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. called the Cuban Missile Crisis “the most dangerous moment in human history.” Scholars and politicians agree that for several days the world was the closest it has ever come to nuclear Armageddon.

But the nature of the risks confronting Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev have been widely misunderstood. For decades, the incident was taught in war colleges and graduate schools as a case study in the art of “crisis management.” A young American president went “eyeball to eyeball” with a Russian chairman and forced him to back down through a skillful blend of diplomacy and force. According to Schlesinger, Kennedy “dazzled the world” through “a combination of toughness and restraint, of will, nerve and wisdom, so brilliantly controlled, so matchlessly calibrated.”

Thanks to newly opened archives and interviews with key participants in the United States, Russia and Cuba, it is now possible to separate the myth from the reality. The real risks of war in October 1962 arose not from the “eyeball-to-eyeball” confrontation between Kennedy and Khrushchev, but from “sonofabitch” moments exemplified by Maultsby and his wandering U-2.

The pampered son of the Boston millionaire and the scion of Russian peasants had more in common than they imagined. Having experienced World War II, both were horrified by the prospect of a nuclear apocalypse. But neither leader was fully in command of his own military machine. As the crisis lurched to a climax on Black Saturday, events threatened to spin out of control. Unable to effectively communicate with each other, the two leaders struggled to rein in the chaotic forces of history they themselves had unleashed.

The countdown to Armageddon began on October 16, with his promise not to deploy “offensive weapons” in when Kennedy learned that Khrushchev had broken Cuba—a U-2, piloted by Major Richard Heyser, had flown over the island two days earlier and taken photographs of intermediate-range Soviet missiles near the town of San Cristóbal. Kennedy branded the mercurial Russian leader “an immoral gangster,” but the American president bore some responsibility for bringing about the crisis. His bellicose, but ultimately ineffective, attempts to get rid of Castro had provoked Khrushchev into taking drastic action to “save socialism” in Cuba. Kennedy imposed a military quarantine on the island and demanded the Soviets withdraw their missiles.

By October 27—the 12th day of the crisis—the two superpowers were on the brink of war. The CIA reported that morning that five of the six Soviet R-12 missile sites were “fully operational.” All that remained was for the warheads to be mated to the missiles. Time was obviously running out. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff presented the president with a formal recommendation to bomb the Soviet missile sites. A full-scale invasion of the island would follow within seven days. Marine units and the Army’s 1st Armored Division would hit the beaches east and west of Havana, along a 40-mile front, in an operation modeled after the June 1944 D-Day landings in France.

It is impossible to tell what would have happened had Kennedy accepted the advice of Air Force General Curtis LeMay and the other joint chiefs. But several things are certain. The risks of a nuclear conflagration were extraordinarily high. And the full scope of the danger was not understood in Washington, Moscow or Havana. None of the main protagonists—Kennedy, Khrushchev or Castro— had more than a very limited knowledge of events unfolding on a global battlefield that stretched from the Florida Straits to the Bering Sea. In some ways, World War III had already begun—aircraft were taking fire, missiles were being readied for launch and warships were forcing potentially hostile submarines to surface.

As Black Saturday dawned, Castro wrote Moscow of his conviction that an American attack on the island was “almost inevitable” and would take place in the next 24 to 72 hours. Unbeknownst to Kennedy, the Cuban leader had visited the Soviet embassy in Havana at 3 a.m. and penned an anguished telegram to Khrushchev. If the “imperialists” invaded Cuba, Castro declared, the Soviet Union should undertake a pre-emptive nuclear strike on the United States. In the meantime, he ordered his anti-aircraft defenses to begin firing on low-flying American reconnaissance planes. Castro declared that he and his comrades were “ready to die in the defense of our country” rather than submit to a Yanqui occupation.

The Soviet commander in Cuba, General Issa Pliyev, was also preparing for war. On his orders, a convoy of trucks carrying nuclear warheads moved out of the central storage depot at Bejucal, south of Havana, around midnight. By early afternoon, the convoy had reached the Sagua la Grande missile site in central Cuba, making it possible for the Soviets to lob eight 1-megaton missiles at the United States. Pliyev also ordered the arming of shorter-range tactical nuclear missiles to counter a U.S. invasion of Cuba. By dawn a battery of cruise missiles tipped with 14-kiloton warheads had targeted the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay from an advance position just 15 miles away.

Kennedy was blissfully unaware of the nature of the threat facing U.S. forces poised to invade Cuba. On October 23, the CIA estimated that the Soviets had between 8,000 and 10,000 military “advisers” in Cuba, up from an earlier estimate of 4,000 to 5,000. We now know that the actual Soviet troop strength on Black Saturday was 42,822, a figure that included heavily armed combat units. Furthermore, these troops were equipped with tactical nuclear weapons intended to hurl an invading force back into the sea. McNamara was stunned to learn, three decades later, that the Soviets had 98 tactical nukes in Cuba that American intelligence knew nothing about.

No one can know for sure whether the Soviets would have actually used these weapons in the event of an American invasion of Cuba. In a cable to Pliyev, Khrushchev had asserted his sole decision-making authority over the firing of nuclear weapons, both strategic and tactical. But communications between Moscow and Havana were sporadic at best, and the missiles lacked electronic locks or codes to prevent their unauthorized use. The weapons were typically under the control of a captain or a major. It is quite conceivable that a mid-level Soviet officer might have fired a nuclear weapon in self-defense had the Americans landed.

“You have to understand the psychology of the military person,” said Colonel-General Viktor Yesin, a former chief of staff of the Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces, when confronted with precisely this scenario. “If you are being attacked, why shouldn’t you reciprocate?” As a young lieutenant in October 1962, Yesin was responsible for preparing the missiles at Sagua la Grande for the final countdown.

There is at least one documented case of a Soviet officer contemplating the unauthorized use of tactical nuclear weapons on Black Saturday. Valentin Savitsky, captain of the Soviet submarine B-59, considered firing his 10-kiloton nuclear torpedo at the destroyer USS Beale as the latter attempted to force B-59 to the surface by dropping practice depth charges. Savitsky could not communicate with Moscow and had no idea if war had broken out while he was submerged. “We’re going to blast them now!” he yelled. “We will die, but we will sink them all!” Fortunately for posterity, his fellow officers calmed him down. The humiliated Savitsky surfaced his vessel at 9:52 p.m.

The unauthorized firing of nuclear weapons was only one of several dangers the world faced at the peak of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The very act of ordering armies, missiles and nuclear-armed bombers to hair-trigger states of readiness created its own risks, which increased exponentially as the crisis progressed.

Mishaps, accidents and near misses occurred on all sides. A U.S. F-106 carrying a nuclear warhead crash-landed in Terre Haute, Ind. A guard at an Air Force base in Duluth, Minn., mistook a fence-climbing bear for a Soviet saboteur, triggering an alarm to scramble an interceptor squadron in Wisconsin. A truck in the Soviet cruise missile convoy moving toward Guantanamo fell into a ravine in the middle of the night, convincing others in the convoy they were under attack. American air-defense radars picked up evidence of a missile launch in the Gulf of Mexico that was later traced to a computer glitch.

Mistakes and miscalculations go hand in hand with war. Some have far-reaching consequences, leading to the pointless squandering of blood and treasure, but they are unlikely to cause the end of civilization. Kennedy understood that a nuclear war is different from a conventional war. There is no room for error. A “limited nuclear war” is a contradiction in terms.

As Maultsby glided across the skies of eastern Russia, a debate raged in the White House over how to respond to a new message from Khrushchev, delivered over Radio Moscow. The Soviet leader had offered Kennedy a deal: The Soviet Union would withdraw its nuclear missiles from Cuba if the United States agreed to remove its analogous missiles from Turkey. Advisers urged the president to reject Khrushchev’s offer, arguing that acceptance would destroy NATO, compromise the American negotiating position and confuse public opinion. Kennedy remained open to the proffered deal.

“How else are we gonna get those missiles out of there?” he asked.

Kennedy’s decisions on Black Saturday were shaped by a lifetime of political and military experience, beginning with his service as a World War II U.S. Navy torpedo boat commander in the Pacific. One lesson he learned from World War II was that “the military always screws up.” Another was that “the people deciding the whys and wherefores” had better be able to explain why they were sending young men into battle in clear and simple terms. Otherwise, Kennedy noted in a private letter, “the whole thing will turn to ashes, and we will face great trouble in the years to come.” He was also influenced by historian Barbara Tuchman’s 1962 book The Guns of August, which described how the great powers had blundered into World War I without understanding why. Kennedy did not want the survivors of a nuclear war to ask each other, “How did it all happen?”

Bypassing his executive committee, or ExComm, the president sent his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, to meet Soviet Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Dobrynin at 8:05 p.m. on Black Saturday. “There’s very little time left,” the younger Kennedy warned Dobrynin. “Events are moving too quickly.” If the Soviet government dismantled its missile bases in Cuba, the United States would end the Cuba quarantine and promise not to invade the island.

“What about Turkey?” Dobrynin asked.

The attorney general told the ambassador that the president was willing to withdraw the American Jupiter missiles from Turkey “within four to five months” but added that the U.S. government would not make any public commitment to do so—that part of the deal would have to remain secret. Although Bobby Kennedy did not set a deadline for a response from Khrushchev, he warned that “we’re going to have to make certain decisions within the next 12, or possibly 24, hours.… If the Cubans shoot at our planes, we’re going to shoot back.”

Like John Kennedy, Khrushchev had come to understand the limits of crisis management. At 9 a.m. on October 28— the 13th day of the crisis—the Soviet premier broadcast another message over Radio Moscow, announcing the dismantling of the Cuban missile sites. He also expressed his concern about the overflight of the Chukot Peninsula by Maultsby’s U-2. “What is this—a provocation?” he asked Kennedy. “One of your planes violates our frontier during this anxious time we are both experiencing, when everything has been put into combat readiness. Is it not a fact that an intruding American plane could be easily taken for a nuclear bomber, which might push us to a fateful step?”

Citing national-security considerations, the U.S. Air Force has yet to release a single document on Maultsby’s adventures. In the book One Minute to Midnight, this author was able to piece together his story from a family memoir, interviews with his fellow U-2 pilots and scraps of information discovered in other government archives. After switching off his engine, Maultsby glided for 45 minutes across the Bering Sea and was eventually picked up by the American F-102s. Maultsby performed a dead-stick landing on an ice airstrip near Kotzebue, on the westernmost tip of Alaska. Numbed from his 10 hour 25 minute ordeal, he had to be lifted out of the cockpit like “a rag doll.” (Charles Maultsby died of cancer in 1998.)

The “sonofabitch who never got the word” was fortunate to survive that day the White House called Black Saturday. So was the rest of humanity.