Castro’s Communist Guerrillas Were Ordinary Cubans With No Money or Training. How Did They Beat Batista’s War Machine?

The revolution didn’t get off to a very good start. Several days after they landed their leaky cabin cruiser on Cuba’s isolated southern coast in December 1956, an exhausted expeditionary force of 82 rebel soldiers led by a cigar-puffing ex-lawyer named Fidel Castro had been decimated by well-armed government troops. Some of the rebels had fled; others had been captured and killed. Escaping from the chaos, Castro took cover in a sugarcane field with two compatriots: Universo Sánchez, his bodyguard, and Faustino Pérez, a doctor from Havana. “There was a moment when I was commander-in-chief of myself and two others,” Castro later admitted.

In a little over two years, however, Castro and his small band of revolutionaries had mustered enough support to overthrow the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. How did they do it?

At the time of his abortive landing on Cuba’s swampy coast, the 30-year-old Castro was already a well-known figure in his homeland. After the Cuban government captured him and put him on trial following a failed attack on a military barracks in Santiago de Cuba in 1953, it had jailed him—and 29 coconspirators—on the Isle of Pines.

Released in 1955 in a prisoner amnesty, Castro made tracks to Mexico City where, under the umbrella of the newly formed 26th July Movement (M-26-7), he recruited and trained a guerrilla force with the intention of returning to Cuba to start a revolution. Despite 18 months of planning, the voyage from Mexico and subsequent disembarkation in Cuba was a disaster. Having survived a baptism of fire in the cane field, Castro and his two remaining companions crept furtively inland toward the safety of the Sierra Maestra, the mountain range that rises sharply from the southeast coast of Cuba. Bereft of supplies and weak with hunger, they dodged army patrols, crawled through sewage pipes, and sucked on sugarcane for subsistence.

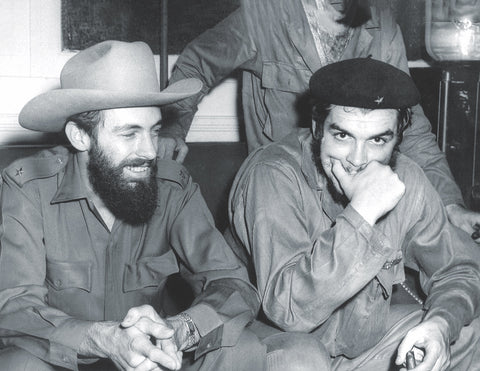

Finally, a week later, they met up with Guillermo García, a farmer who was sympathetic to the rebel cause, and their luck started to change. In mid-December 1956 at the small village of Cinco Palmas, Castro’s brother, Raúl—who unbeknownst to Fidel had also escaped from the skirmish in the cane field—emerged from the jungle with three men and four weapons. Castro was elated. Three days later, eight more soldiers, including Che Guevara

and Camilo Cienfuegos, showed up, swelling the ranks of weary rebels to 15. “We can win this war,” a reinvigorated Castro told his small band of ragged soldiers. “We have just begun the fight.”

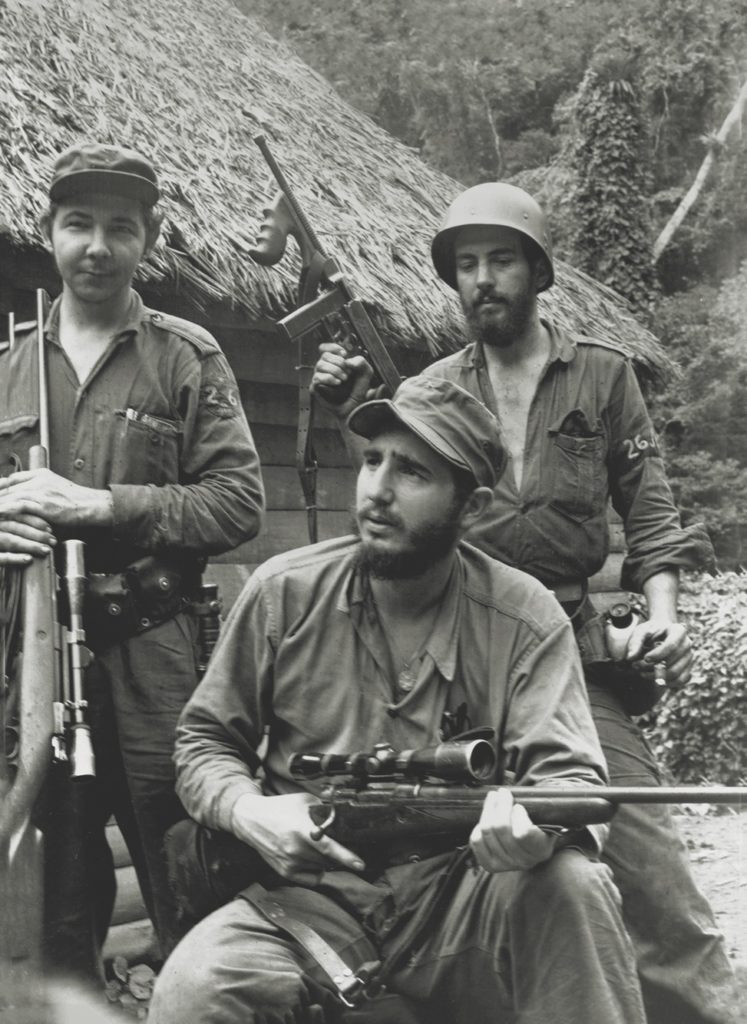

History likes to portray the early days of the Cuban revolution as a classic David-and-Goliath battle between a bullying government and a small band of poorly equipped rebels. It wasn’t quite that simple. Despite his charismatic personality and dogged determination to succeed whatever the cost, Castro wasn’t Cuba’s only revolutionary in the late 1950s. Others, acting clandestinely in Cuba’s towns and cities, were equally intent on bringing down Batista’s authoritarian government, which had brazenly seized power in a 1952 coup. Without these rebels and the grassroots support they sowed among the Cuban people, the revolution might not have been possible.

One of them was Frank País, a young teacher from Santiago de Cuba who had become increasingly politicized after Batista’s audacious power grab. Forming a small opposition group in Santiago, he secretly merged with Castro’s 26th July Movement in 1955. Rather than relocating to Mexico, however, País decided to remain in Santiago, where he coordinated a well-organized underground resistance to the Batista regime. It was from here that he planned an urban uprising in late 1956 to coincide with the landing of Castro’s expeditionary force on the southern coast. Later, when Castro was safely installed in the mountains, País collaborated closely with the rebels, forming a vital link between the underground cells in the cities and the revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra. More visible and vulnerable than Castro in the hot, sticky backstreets of Santiago, País was ultimately tracked down and murdered by Batista’s police in July 1957. He was just 22. But even in death, his ideas lived on. He had already played a vital part in launching the Cuban revolution.

Celia Sánchez was the daughter of a Cuban doctor from Manzanillo, a small city on the cusp of the Sierra Maestra. Inspired by Castro’s 26th July Movement, she formed her own cell in Manzanillo and provided a vital conduit for the nascent rebel army, sending supplies and new recruits up into the mountains. By 1957 she had moved permanently to the Sierra Maestra hideout, becoming the first woman to join the revolutionaries and ultimately forming the Mairana Grajales Brigade, an all-female military platoon, in 1958. In time, she also became Castro’s lover and closest confidant.

A cornerstone of Castro’s early success was his ability to use the news media to advance his cause. In February 1957, with Celia Sánchez’s help, Castro lured Herbert L. Matthews, a reporter for the New York Times, to meet him at a secret location in the Sierra Maestra for an exclusive interview. Ever since the skirmish in the cane field, the Cuban press had erroneously reported that Castro was dead. Incensed, Castro wanted to loudly announce to the world that he was very much alive and ready to fight.

During his meeting with Matthews, Castro boldly exaggerated the size of his army and arranged for the same handful of men to repeatedly march by to give the journalist the impression that he was harboring a significant military force. The trick worked. Matthews was smitten. His story in the New York Times a week later began: “Fidel Castro, the rebel leader of Cuba’s youth, is alive and fighting hard and successfully in the rugged, almost impenetrable fastnesses of the Sierra Maestra.”

It was one of the biggest newspaper scoops of the 20th century and the first of several propaganda coups for Castro in which he was able to paint himself as a heroic outlaw to the foreign press.

If Castro was Robin Hood, Batista was quickly becoming an unsavory Prince John. As challenges to his increasingly corrupt regime mounted, so did the resulting repression. An attempted attack on the presidential palace in Havana in March 1957, led by student leader José Antonio Echeverría, was ruthlessly suppressed. A naval mutiny in the city of Cienfuegos in September was snuffed out with bombers and tanks.

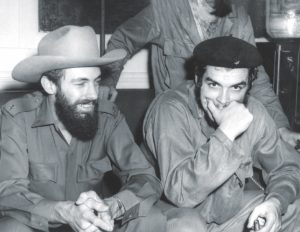

Concealed in the Sierra Maestra, Castro and his growing band of revolutionaries managed to avoid that fate. Emerging sporadically from the mountains and using guerrilla tactics, the rebels scored an early victory in January 1957 when, with just 23 functioning weapons, they stormed a small army barracks on Cuba’s south coast. Four months later, the rebels, now numbering 127, successfully overran a military garrison in the coastal town of El Uvero. From the humid days of spring 1957 until the final rebel victory in 1959, Cuba remained in a simmering state of civil war.

Many in Castro’s original expeditionary force, having no military experience, could barely fire a rifle. But forced to learn fast in the active “training fields” of the Sierra Maestra, a significant proportion of those who survived the disastrous landing evolved into competent soldiers and leaders.

Ernesto “Che” Guevara, an Argentine doctor, had joined the mission in Mexico City in 1955 as group medic. After forsaking his medical kit for a box of ammunition during the ambush in the cane field, he quickly grew into a fearless warrior.

Guevara became Castro’s right-hand man, an effective and ruthless guerrilla fighter who expounded a rigid socialist ideology and led by example in battle. Brave, disciplined, and zealously committed, he also had a darker side. Showing little mercy for captured informants, he sometimes executed them himself. But at the same time, Guevara played a key role in advancing the lot of the impoverished people in the mountains. Under his leadership, schools were established and bread ovens built. These and other such small-scale infrastructure projects that took root in remote Cuban villages were crucial in sealing the continued support of the rural working class. Without their backing as runners, guides, and volunteers, Castro would have struggled to gain a foothold in the mountains.

Cienfuegos, a Cuban from Havana who had been one of the last recruits to join Castro’s expeditionary force in Mexico, proved to be Guevara’s equal as a soldier and leader. He was made a military commander in 1957, and the following summer he formed one of two columns that Castro sent west to ultimately occupy the rest of Cuba.

Guevara and Cienfuegos were complemented at the top of the rebel command chain by Raúl Castro and Juan Almeida, both veterans of the Moncada Barracks attack in 1953. They had served their prison senten-ces alongside Fidel on the Isle of Pines. Raúl was young (only 25 in 1956), impulsive, and less charismatic than his hotheaded brother. Almeida was the rebels’ only Afro–Cuban commander and an important symbol for a revolution that professed to be nondiscriminatory and egalitarian.

It was this tight core of “comandantes” who helped establish Castro’s first permanent base in the Sierra Maestra in 1958, a well-camouflaged military camp nestled in the cloud forests ringing Cuba’s highest peaks that became known as Comandancia La Plata.

La Plata was rustic but sophisticated and well hidden: Batista’s troops never found it. It was from here, under the supervision of Che Guevara, that the rebels set up their own radio station, Radio Rebelde, as an alternative source of news and propaganda to Cuba’s state-controlled press.

As Batista’s repression spread, so did his unpopularity. Refusing to take the growing military threats seriously, the Cuban president chose to use his secret police to harass, torture, and publicly execute people suspected of aiding and abetting Castro’s band of barbudos (bearded ones). Not surprisingly, the ugliness prompted a backlash, not just among Cubans—who gradually deserted the government in favor of the 26th July Movement—but also among Batista’s foreign allies. In March 1958, as the regime’s excesses grew ever more discomforting, the U.S. government imposed an arms embargo on Cuba and recalled its ambassador. At the same time, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, hedging its bets on the outcome of the conflict, secretly began channeling some $50,000 to the 26th July Movement (an irony given its later plots to assassinate Castro).

By the summer of 1958, Batista was beginning to see Castro as a genuine force and a perennial thorn in his side. Understanding the need to smoke the rebels out of their mountain hideout for good, he dispatched General Eulogio Cantillo to the Sierra Maestra to oversee a major military offensive that was dubbed Operation Verano, or “Plan FF” (Fin de Fidel).

With his popularity imploding and his foreign allies abandoning him, it was Batista’s last throw of the dice. But despite a minor victory at the Battle of Las Mercedes in August 1958, Operation Verano failed to quash the rapidly spreading rebellion. Part of the problem was poor military intelligence. Many of Cantillo’s decisions were based on his assumption that the rebel army was far bigger than it actually was (it was perhaps 3,000-strong by summer 1958, but historical reports vary and Castro’s own reported figures fluctuated wildly).

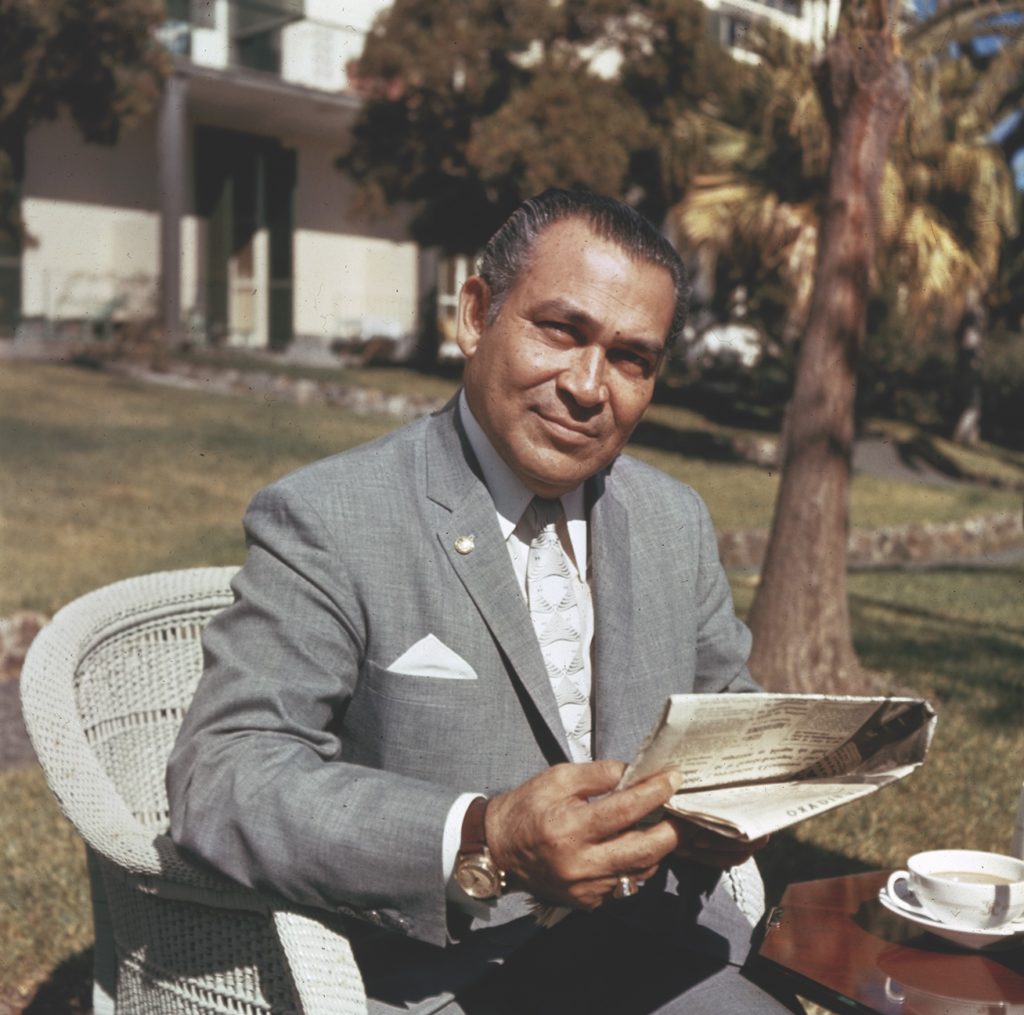

One certain advantage that Castro had was the motivation and morale of his followers. The rebels were bonded by the spirit of the underdog. Not only were they fighting for their lives, but—in the days before Castro cast his lot with the Soviet Union—they were inspired by ideology and the dream of a better future. Sympathetic journalists and photographers elevated them to the realm of romantic myth. Before the 1961 Bay of Pigs debacle and friendly visits to Moscow soured the relationship with the United States, the revolutionaries were seen as virtuous cowboys cleaning up Cuba’s “wild east.”

On the contrary, Batista’s army of 12,000 paid conscripts was carrying out the dirty work of an increasingly embarrassing dictator. Many soldiers refused to fire their weapons. Some even secretly defected.

With Operation Verano derailed and Batista’s tactical decisions becoming increasingly irrational, the end looked to be in sight. Sensing a groundswell in popular support across the country, Castro sent Guevara and Cienfuegos, his two senior commanders, on a long march west to Las Villas Province in an attempt to cut the country in two. It was the first time in nearly two years that the rebel army had come down from the mountains to face the enemy on open ground.

The tentative and largely clandestine advance took seven weeks, with the rebel columns mostly covering ground at night in tough, unfavorable conditions. But support across the country was growing. The inexperienced but tightknit group of revolutionaries found they picked up new recruits wherever they went. Their numbers quickly doubled.

By late December 1958, both columns had taken up strategic positions in central Cuba: Guevara outside the city of Santa Clara and Cienfuegos 50 miles to the east near the settlement of Yaguajay. Cienfuegos acted first, attacking a well-defended military garrison on the settlement’s outskirts. The government soldiers managed to hold out for 11 days before they ran out of ammunition on December 30.

By this point, Guevara was in the midst of a battle for Cuba’s fourth largest city, Santa Clara, with his force of 350 men, many of them barely out of their teens, outnumbered 10 to one. Undaunted, the rebels fearlessly derailed an armored train, capturing its weapons and cutting communications. Tired, dejected, and torn by conflicting loyalties, the city’s leaders surrendered. The action that turned out to be the death knell for the Batista regime had ultimately been achieved with a couple of bulldozers and a hail of Molotov cocktails.

Hearing of Santa Clara’s capitulation at a glitzy New Year’s Eve party at Camp Columbia in Havana, Batista panicked and fled the country. Boarding a plane with 40 cohorts and $300 million in cash, he headed to the Dominican Republic (the U.S. government refused to have him), where he was greeted by President Rafael Trujillo, another soon-to-be-deposed despot.

Acting swiftly to offset a military coup, Castro stationed himself on the western approach to Santiago de Cuba and threatened to invade the city if it refused to surrender. Protecting him on his eastern flank, Raúl Castro stood guard over Guantánamo, while Guevara and Cienfuegos headed directly for Havana.

Facing a juggernaut of revolutionary fervor, Santiago’s military leaders surrendered without a shot being fired, and from the balcony of the city hall on New Year’s Day in 1959, an ecstatic Fidel Castro announced the “triumph of the revolution.” Across Cuba, jubilation was mixed with confusion and trepidation. In Havana, casinos were looted, parking meters were smashed, and a Cuban farmer marched his pigs into the lobby of the five-star Hotel Riviera, then owned by Meyer Lansky, the richest and most powerful American mafia boss.

The war seemed to be over. Castro began a triumphant, weeklong procession across the country, Guevara took up residence in Havana’s Cabaña fort, and in a middle-of-the-night interview with Ed Sullivan, the U.S. television host, in Matanzas, Cuba’s new Maximum Leader claimed in faltering English that he was a democrat.

The euphoria, however, didn’t last long. Within just six weeks, ruthless reprisals, including show trials and executions, were being meted out with fresh zeal by Cuba’s fledgling revolutionary government. The cycle seemed to be starting all over again.

this article first appeared in military history quarterly

Facebook @MHQMag | Twitter @MHQMagazine