Can You Help Solve These Gettysburg Photo Mysteries?

The Amos Humiston story resonates like few others from Gettysburg. On July 1, 1863—Day 1 of the epic, three-day battle—a local resident discovered the body of the 154th New York Infantry sergeant near John Kuhn’s brickyard, north of the town square. The soldier clutched in his hand an image of three children. He carried no identification.

To identify the children and thus reveal the soldier’s name, a doctor had hundreds of cartes-de-visite of the photograph created and distributed. “Whose Father Was He?” read the headline above a story about the image in The Philadelphia Inquirer and other Northern newspapers. The publicity effort worked. Months after the battle, Humiston’s widow identified him after reading a detailed description of the photograph of the children in a religious publication.

But the Humiston saga wasn’t the only mystery involving Gettysburg photographs. In the immediate aftermath of the battle, burial crews discovered other poignant images—a torn portrait of a fiancée, a blood-spattered image in a captain’s stiff fingers, a baby’s likeness smeared with blood, and many others—among bodies, bibles, scraps of letters, clothing, and weaponry.

In November 1867, a daguerreotype of a woman—in her early 20s with “dark hair, combed back and falling loosely over her shoulders”—was unearthed, along with a soldier’s remains and a cartridge box containing 43 bullet, near the Emmitsburg Road at Gettysburg Based on the location on the battlefield, the grave was believed to belong to a fallen Confederate. As one newspaper reported: “We have been particular in describing the daguerreotype, as it may lead to its identification.”

Identification of this soldier and the image of the young woman, however, were not ascertained. The names of other subjects in photographs found on the battlefield also have been lost to history.

But enough clues have surfaced for us to inch closer to solving two other Amos Humiston-like Gettysburg mysteries. Each involves a Confederate soldier, whose remains—like Humiston’s—were found with a mysterious photograph. We don’t have all the answers yet.

So, jump-start your brains, log on to genealogy sites, and scour old newspapers. More than 158 years after one Gettysburg photo mystery was settled, you can assist in solving two more.

Confederates attacking

the center of the Union lines during Pickett’s Charge on July 3,

1863—Gettysburg’s third day—were repelled, resulting in more than 50 percent

total casualties. (Bridgeman Images)

A Bloody Souvenir

At about dawn on July 4, 1863, the 87th anniversary of the creation of the United States and the day after Pickett’s Charge, Russell Glenn of the 14th Connecticut Infantry searched the battlefield with comrades near the Bloody Angle. The soldiers found a “terrible valley of death”: bloodied and battered enemies, body parts, and the detritus of war.

While some of Glenn’s comrades assisted wounded Rebels, others searched for war trophies, a common activity of soldiers following a battle. Then the 19-year-old corporal happened upon a Confederate lying face up near a boulder, his blue eyes wide open as if staring at the sky.

He is handsome — even noble-looking — _and so lifelike that he appears he can speak, _Glenn thought to himself about the fallen enemy, perhaps a teen. Then he noticed the gruesome, bloody hole in the Rebel’s chest, perhaps from a bullet or canister, and knew death must have come quickly.

When Glenn stooped to examine the curly-haired Confederate, clad in a gray blouse and coat, he noticed something in his hand, near his left breast. He broke the death grip and examined the object, a daguerreotype of a young woman in her late teens or early 20s. She was clad in a high-necked dress with what appeared to be a brooch pinned near the top. Her hair, parted in the middle, formed a bun. With a Mona Lisa–like hint of a smile, she stared straight ahead. The case was battle-damaged, but the image itself remained unscathed.

Glenn wondered if the photograph was a sweetheart: Did this man stare at the image as he died? Using the Confederate’s coat, the teen wiped blood from the photograph’s glass cover and slipped the souvenir into his coat pocket. Burial crews tossed the remains of the unknown soldier—perhaps from the 16th North Carolina or an Alabama regiment—into a long trench with dozens of his comrades.

Glenn was slightly wounded in the head and face at Gettysburg, severely wounded in the breast at Hatcher’s Run, near Petersburg, and suffered two other war wounds. By February 1865, he had become a 1st sergeant for the hard- fighting unit that had seen action at Antietam, Fredericksburg, Morton’s Ford, and elsewhere. But Glenn survived the war and returned to Bridgeport, Conn.

As a civilian, Glenn served as a police officer and a truant officer and became an influential member of veterans’ organizations. The war—and the Gettysburg photograph he had brought home with him—remained seared into his brain. In 1911, Glenn gave such a graphic description of Pickett’s Charge to a Grand Army of the Republic gathering that “the audience had but little difficulty in seeing why” Confederates “gladly surrendered after their awful experience.”

Two years later, weeks before Glenn attended a 50th anniversary reunion at Gettysburg with 14th Connecticut comrades, a Bridgeport newspaper made the daguerreotype subject of a P. 1 story. “Glenn’s Trophy Tells Tragedy of the Civil War,” the headline read, followed by “Worn Daguerreotype Is Token of Romance Blighted by Conflict” and “Bridgeport Soldier Has Not Sought to Restore It Fearful of Causing Heartaches.”

Concluded the newspaper: “This little incident of a terrible battle, one of a thousand too trivial to be noticed by the historian yet a mighty reason why there should be no more war, remained to be told by the camp-fire and after the war about the fireside.”

After the war, the story explained, Glenn tried to find the young lady in the daguerreotype, which had remained in the veteran’s possession since its discovery. “A woman who lost [a] father, brothers and [a] sweetheart at Gettysburg is believed to be the original of the picture,” the newspaper reported. Glenn was certain of her identity, but he was “fearful of reopening an old wound [and] he refrained from communicating with her.”

Frustrating future historians and amateur detectives, the newspaper offered no name or other clues that could lead to the identification of the woman or the fallen Confederate found with the photo.

A monument to the 14th Connecticut Infantry was

dedicated near the Bloody Angle on July 3, 1884—21 years after Corporal

Russell Glenn found his photo mystery near the same spot. (Photo by Steve A.

Hawks, courtesy stonesentinels.com)

In 1906, a copy of the image appeared in the 14th Connecticut regimental history. In the accompanying text, Glenn called the photograph “the most valuable relic of his war experience.”

On November 29, 1919, the morning after he attended the funeral of a friend, Glenn died of heart disease at 74. He left a widow and two sons. No mention of the veteran’s prized Civil War souvenir appeared in his obituary in The Republic Farmer , a local newspaper.

The fate of the image, as well as the names of the subject and owner, remains unknown. Perhaps with deeper research, more information will surface about Glenn and the photograph that had such an impact on his life. He, of course, wasn’t the only veteran to have an extraordinary experience involving an image found on the battlefield.

Postwar Discovery

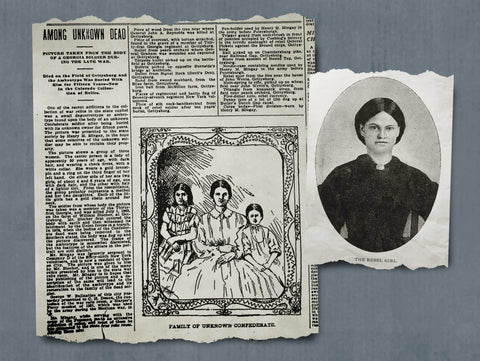

On a warm day in late July 1878, as Confederate fallen were exhumed on William Blocher’s farm north of Gettysburg, a skull surfaced from a grave; so did a “C.S.A”-stamped belt buckle, a brass “3,” “1,” and “F” from a kepi, and other accoutrements. And, as a Civil War veteran Henry Mark Mingay watched the tedious work, a remarkable artifact appeared between two rib bones: an ambrotype—a photograph produced on a glass plate—of two girls and a young lady.

The woman, with jet-black hair and red-tinted cheeks, appeared to be in her late 20s. The children, between four and 10 years old, had the same features as the young lady. Newspapers published contradictory reports on how the photo ended up with Mingay, who was visiting Gettysburg with comrades.

“The case had decayed,” a Gettysburg newspaper reported days after the discovery, “but the picture is still perfect, showing features, clothing, coloring and gilding with the clearness of recent taking.”

Based on the etching on an old grave marker and the company and regimental designations from the kepi, the Confederate served with the 31st Georgia. (Another newspaper account noted that the fallen Rebel served with the 7th Georgia, but Blocher said he was a 31st Georgia soldier.)

On July 1, the 31st Georgia fought across the Blocher Farm north of Gettysburg. But no identification was found with the fallen soldier in Company F, a unit raised in Pulaski County. Could the soldier’s wife and children be the subjects in the ambrotype—“their last gift to papa,” as a Pennsylvania newspaper speculated days after its discovery?

The corpses of

thousands of soldiers covered the Gettysburg battlefield in the days after the

three-day battle. Many were buried in shallow graves, but not before being

picked over for mementos or treasures. (Library of Congress)

Like Russell Glenn’s relic, the Blocher Farm photograph has a tantalizing history—one intertwined with Mingay, a diminutive man with a keen sense of humor. “A natural ham,” a newspaper reporter once called him.

Born on December 3, 1846, in Filby, England, Mingay immigrated to the United States with his family in 1850, eventually settling in Saratoga, N.Y. In 1860, he left school to become a shoe shiner and a “printer’s devil”—an apprentice in a newspaper’s printing department. In April 1861, he heard news of the shelling of Fort Sumter from a telegrapher, who told him to sprint like hell to deliver word to his employer.

On August 29, 1864, 17-year-old Mingay enlisted as a private in Company D of the 69th New York—part of the famed Irish Brigade—and served through the rest of the war. In June 1865, he mustered out as a sergeant.

After the war, Mingay was active in veterans’ organizations—it was at Grand Army of the Republic event in Gettysburg that he acquired the ambrotype, possibly from Blocher, who reportedly witnessed the 31st Georgia soldier’s burial by U.S. Army soldiers in 1863. Mingay took the treasure home to Penn- Yann, N.Y., intent on returning it to the fallen Georgian’s family.

In August 1878, a Gettysburg newspaper reported Mingay planned to “have the facts [about the image] well published, with the view to the restoration of the picture to the family of the deceased.” According to another Pennsylvania newspaper, the photograph was taken to Philadelphia, where copies were to be made and then sent to Georgia “in the hope of discovering the relatives of the dead soldier.” But it’s unknown whether the ambrotype ever made it to Philadelphia or any copies were made and distributed.

In 1897, the photograph’s trail picks up in Colorado, where Mingay had moved 12 years earlier. By the late 1890s, the successful newspaperman was interested in finding a home for his collection of other war relics—mementos that included not only the photograph, but a piece of the tree near where a bullet fatally wounded Union Maj. Gen. John Reynolds at Gettysburg; a penny dug up at Dutch Gap Canal in Virginia; a pen-holder Mingay used at Petersburg; slivers of the 77th New York’s regimental and battle flags; and a piece of overcoat, with the button attached, from the 31st Georgia soldier’s grave.

In August 1897, Mingay donated artifacts—including the prized ambrotype and the button attached to the overcoat—to the State of Colorado for inclusion in a display of war relics at the state capitol in Denver. Even 34 years after the battle, Mingay hoped the soldier’s relatives might claim the photograph.

This article first appeared in America’s Civil War magazine

Facebook @AmericasCivilWar | Twitter @ACWMag

In The Rocky Mountain News on August 16, 1897, a story about the veteran’s donations included an illustration of the ambrotype with this description:

“The center person is a lady of apparently 30 years of age, with dark hair, and wearing a check dress, with a white collar. She wears a gold breast-pin and a ring on the third finger of her left hand. On either side of her are two girls…one with dark hair of a lighter tint….Each of the girls has a gold chain around her neck.”

The frame of the ambrotype was “somewhat discolored,” the newspaper reported, “but the features of the sitters in the portrait are still distinct.”

The day of the story’s publication, the custodian of Colorado’s war relics mailed a copy of The Rocky Mountain News article to Georgia’s adjutant general with a letter seeking assistance in identifying the subjects of the portrait. “I was a soldier in the federal army,” wrote Cecil A. Deane, “and know how greatly the ambrotype will be regarded if its rightful owner can be found. It will afford me great pleasure to assist in restoring it to such person.”

A week later, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reprinted the illustration with details about the ambrotype’s discovery. “Who Claims This Picture?” read the headline. The answer was in the veteran’s own backyard.

In a front-page story in The Denver Post on November 24, 1897, “Mrs. Frank Smith” wept as she stared at the ambrotype during a visit to the war relic museum in Denver. Those are my sisters, _the Como, Colo., woman _ declared. The soldier it was found with is my brother. One of the sisters in the ambrotype also lived in Como. The newspaper did not report the whereabouts of the other sister.

GET HISTORY 'S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Close

Thank you for subscribing!

Submit

In 1861, “Mrs. Smith’s brother enlisted in the Confederate army, taking with him the picture answering identically this description of this one,” the Post reported. Added the newspaper: “A peculiar feature of this case is the fact that the man who found the picture, and two of the women whose portraits are on it, live in Colorado.”

But the Post left out many vital details, including: _ Who was Mrs. Frank Smith? What was her maiden name and names of her sisters and fallen brother? Neither the _News nor the Post followed up on their Gettysburg photo stories.

At Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, only three soldiers in the 31st Georgia in Company F—the “Pulaski Blues”—suffered mortal wounds: Privates Samuel Jackson and Thomas Lupo and Sergeant George H. Gamble. Could one of these soldiers be linked to “Mrs. Frank Smith”? Searches on ancestry.com and other genealogy sites have failed to yield a definitive answer.

In 1914, Mingay—one of the men who inspired this hunt—moved from Colorado to California. Thirty-one years later, the blind widower married again, after a 12-year courtship—his new bride was 68; he was 98. “I’m the luckiest boy in the world,” the oldest member of the Nathaniel Banks Grand Army of the Republic Post of Glendale, Calif., told reporters after the nuptials.

Henry Mingay and his photo discovery periodically made

newspaper headlines. Mingay, who became a local celebrity after moving to

California, lived to be 100 years old. (Burbank Times)

When Mingay died at 100 in 1947, the local celebrity left behind a daughter, three grandchildren, eight great-grandchildren and a Burbank (Calif.) elementary school that bore his name. Like the fallen 31st Georgia soldier, the “Three Young Ladies in the Gettysburg Grave” photograph remained an enigma.

In 2021, the most tantalizing clue of all surfaced online—the location of our mystery photograph was revealed as the History Colorado Center museum in Denver. An examination of the image could uncover a name on the plate or another clue. But like wisps of gun smoke on a battlefield, the photograph has disappeared in the museum’s collection. “[A digital copy] of the image that you have requested and paid for is inaccessible to us at this time,” wrote a museum representative.

John Banks is the author of two Civil War books and his popular Civil War blog (john-banks.blogspot.com). Banks, who never misses an episode of the crime show Dateline on TV, loves mysteries. He lives in Nashville, Tenn.