At Auschwitz, Jews Composed Music in Secret. Now Their Works Are Being Performed in London.

After more than 80 years and many different lives away, the reverberations of the heartbreaking melody, “Futile Regrets” was heard inside a concert hall in London.

The song, reports the Washington Post, is part of a collection of more than 210 pieces of music found in the archives at Auschwitz, never played, until now.

In 2015, British composer and conductor Leo Geyer stumbled upon the historic ephemera while on a trip to the Nazi death camp after he was commissioned to create a piece honoring historian and Holocaust expert Martin Gilbert.

“I had a conversation with one of the archivists, and he said in a somewhat offhand way that there were some [musical] manuscripts in the archive,” Geyer explained to the Washington Post. “I nearly fell over at the time when he mentioned it because I couldn’t believe that such a thing could exist and that it had been overlooked all this time.”

From its opening in 1940 to the camp’s liberation in 1945, over 1.1 million men, women and children were systematically murdered at Auschwitz. More than 11 million were killed in the Holocaust — six million of whom were Jews.

During these five years music provided comfort — but also became a beat to its seemingly never ending horrors.

The Nazis used the arts “as part of the murder machine,” Norman Lebrecht, a British music journalist, told the German media outlet DW.

“Our task consisted of playing every morning and every evening at the gate of the camp so that the outgoing and incoming work commandos would march neatly in step to the marches we played,” Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, an Auschwitz survivor who played the cello at the camp, relayed to CNN.

“We also had to be available at all times to play to individual SS staff who would come into our block and wanted to hear some music after sending thousands of people to their death,” she continued.

Despite being intertwined with such hell, music was also a way for Jewish prisoners to express their pain and terror.

It was “a chink of daylight in the darkness,” Geyer stated to the Washington Post.

“Jews being held in concentration camps were unable to document what was happening to them by conventional means. Writing down or photographing this would have been impossible, so they turned to a long cultural tradition of telling their stories through songs and music,” historian Shirli Gilbert said in a news release. “ … Away from the eye of the SS officers, Jews secretly created their own music as a means to cope, survive and document.”

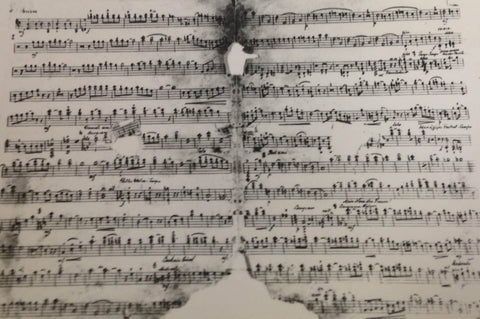

However, the task of bringing the camp music back to life was a tall order for Geyer. Many of the sheets of music were partially destroyed, burned along the edges or tragically, never completed.

Further complicating matters, writes the Post, was the fact that the orchestras often used a “hodgepodge of random instruments that were available,” Geyer said, including some that are not traditionally used in orchestras like accordions, saxophones and mandolins.

Geyer took it on as his mission to stitch together a proper coda to honor the victims of Auschwitz — a feat that would take more than seven years, extensive research, interviews with survivors and six visits to Auschwitz.

On Monday, Geyer’s work came to fruition as violin strings played the sorrowful sounds of a now completed “Futile Regrets” and three other pieces found at Auschwitz.

“I’m not Jewish, Romani, Polish, Russian or disabled, or descended from any person from Auschwitz,” Geyer told the Post. “But I do stand by those who are persecuted for no reason other than who they are. And I hope to live in a world where no evil could rise again.”