Antietam Aftermath: How the Ravages of War Devastated the Town of Sharpsburg

Steve Cowie spent 15 years researching how the Battle of Antietam and the following military occupations affected the prosperous small town of Sharpsburg, Md. Captivated by the Civil War since childhood, Cowie used skills developed as a screenwriter to shape the myriad details he uncovered into an affecting narrative of the tornado of war that repeatedly touched down on the villagers’ landscape. The battle’s legacy is more than the thousands of casualties; the troop presence changed Sharpsburg in many ways and forever. By probing the war claims that Sharpsburg farmers submitted for property lost during the military occupation, Cowie’s When Hell Came to Sharpsburg (Savas Beatie, 2022) opened a window on the war’s long-lasting consequences for Sharpsburg.

Why did you focus on Sharpsburg?

Steve Cowie

When I began I really focused only on just the battle and the 1862 Maryland Campaign. After studying the battle and the region, that’s when I really began to feel a pull toward the civilian aspect. Part of the reason I was able to find so much is that I had spent a number of years studying the genealogies of these people and the land records to determine who lived in Sharpsburg in 1862 and where. So I knew exactly who I was looking for when I arrived at the National Archives to examine war claims. I had to go through the 250 individual claims and analyze them on a claim-by-claim basis.

What made Sharpsburg unique?

Number one, it was the battle itself, the bloodiest day in American history as many historians have cited, and just the magnitude of that battle, the terror and the stress inflicted on the people, and the horrible aftermath with all the bodies and the dead horses. But what really made it unique, unlike Gettysburg and Monocacy, is that the Army of the Potomac, McClellan’s army, decided to stay in Sharpsburg after the battle. In those other campaigns, the armies fought and left, leaving their wounded and medical personnel behind. Most of the Army of the Potomac camped near Sharpsburg for six weeks. There’s an abundance of evidence to show these 75,000 troops were poorly supplied, and as a result they had no choice except to live off the people, so to speak, and use their homes and farms as their supply depots. The river crossing known as Blackford’s Ford, Shepherdstown Ford, or Boteler’s Ford was the biggest portal between Confederate Virginia and Union Maryland between Harpers Ferry and Williamsport. Because of that ford, Confederate divisions actually bivouacked at Sharpsburg during the Gettysburg and the Monocacy campaigns. These Confederates attracted Federal forces to the area who ended up encamping near the ford as well. And all these poor farmers who were struggling to recover from Antietam were devastated by property losses in 1863 and 1864. So, though those campaigns do not relate to Antietam, they really did inflict setbacks on those struggling to recover. And that’s another way I like to see Sharpsburg as being a different community in the war. It was hit by multiple campaigns.

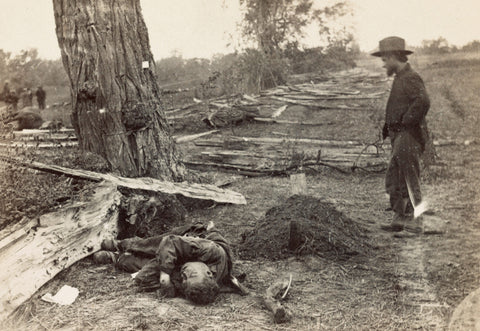

Talk about the immediate aftermath of the battle of Antietam.

The estimate on the map by S.G. Elliott, a cartographer who visited Sharpsburg in 1864, is more than 5,800 soldiers were buried just in the area where the combat occurred and near the battlefield. WHO and the CDC studies well document that dead bodies don’t cause disease outbreaks, but what happens if one of those bodies had typhoid fever at the time of its death? You throw in all the dead horses and the thousands of tons of manure from the animals that were there after the battle that contained pathogens such as E. Coli and other dangerous bacteria. With all the human waste of 75,000 soldiers and the hundreds of livestock carcasses butchered by the army, it gives pause to think about how much waste and dangerous materials could be washed into the groundwater or transmitted to areas where food is served by the swarms of houseflies that were all over the battlefield for weeks.

What did you find in the records of local Dr. Biggs?

His original daybooks provided a wealth of information. I was able to look at his house calls in early 1862 and track them through late 1863. Starting in late September after the battle, there is a spike in the calls, quadrupling by November 1862, and the number of patients also expanded. Those numbers return to normal about May of 1863. He logged the name of each person he saw, the day he saw them, and the medicine he dispensed.

Wood was a critical resource for the armies. Talk about what happened to

the fencing on Sharpsburg farms.

It was not uncommon for Sharpsburg farmers to have seven, eight, nine different fields that were all fenced at the time of the battle. Some contained wheat; some farms had one or two corn fields; some had potato patches, orchards, clover fields, all of them fenced to keep animals from devouring the crops. It was miles and miles of fencing on some of these farms, which could be 260 or 320 acres. So when you consider the boundary fencing, any fencing that went along farm lanes, around barns, around gardens near the houses—it was a labyrinth of fencing that took years to construct and, according to the claims, all of it disappeared on many farms. This was extremely expensive and laborious to replace. The loss of all this fencing was devastating to Sharpsburg. There was one account, one resident talked about how disorienting it was to navigate home in the darkness, without all that fencing to aid in deciding where to turn and so forth. It was described by multiple witnesses as a bare commons, unrecognizable as this barren plain.

Describe the impact of burials on these farms.

Dead bodies had been sitting out for two to three days before the Union burials occurred. And then the Confederate burials took place after that. With the difficult limestone land of Sharpsburg, and the rush to inter all these remains, most of these graves and burial trenches were very shallow. There were no coffins for the bodies in the mass graves, so it didn’t take much for a hard rainfall or a foraging animal to expose the remains, and many of these remains were exposed a week after the battle. One visitor in 1865 to David Miller’s farm was shocked to see skulls and femur bones lying about. A farmhand explained that Miller had lost so much fencing from the battle that he had only one spot on his farm that was still enclosed. All of his livestock had been slaughtered by the troops. He had been able to acquire new hogs and the only place to put them was in this enclosed field that contained burial trenches. The hogs uprooted the dead, and there are several accounts of visitors to the area being mortified at seeing foraging hogs walking around carrying a human limb in its mouth. Really nightmarish stuff. It was the desecration of these bones that shocked a lot of people to complain, and eventually the state of Maryland decided to take action and pay proper respect to the Union dead by establishing the national cemetery. A lot of it had to do with these bones that were scattered everywhere. It was terrible.

Union artillery shells badly damaged the 1768

Lutheran Church on the east side of Sharpsburg.

You looked through many of the claims for lost property, and found strict

limitations on what could be claimed. Talk about the longstanding impact.

With the devastation of the war and the postwar economy, along with the

inflation and the minuscule war claims, or the rejected war claims, a lot of

people either lost their homes to bankruptcy, or they had to sell them, just

to start their lives over, like the Philip Pry family. Due to all these

combined issues, a lot of residents got swept up in westward migration. They

decided to start their lives over by migrating to Illinois, Kansas, especially

California. A lot of prominent Sharpsburg-area farmers saw their children

emigrate to California. Eventually the tourism that came in when a railroad

depot was established, around the 1880s, brought a lot of veterans into the

area for the Antietam reunions. Over time Sharpsburg began to recover because

of increased tourism to the area and also due to the Chesapeake and Ohio

Canal, which employed a number of residents in the 1870s

and 1880s.

What did you find most surprising after all your study?

I didn’t expect so many people in the five-mile radius of the battlefield to have suffered such devastating losses to their livestock, grains, and fencing, but as was told by a lot of evidence and the testimony of the claims, the Army of the Potomac moved toward the river once the Confederate army left Maryland on the night of September 18. Once the fencing disappeared near the camps along the river and all the available grains for the forage for the army animals, a lot of these soldiers started going east, more toward farms near the battlefield or even beyond that to property closer to Antietam Creek to load up wagons with food, fence rails, and animal forage and bring it back to their camps closer to the Potomac River. I didn’t expect this amount of devastation over the six-week period. It was amazing in other words how much an army can consume just by being in camp. An all-devouring machine. I just don’t think anyone—nor myself when I started this project—was able to envision not only the amount of property destroyed but the expanse on which it was destroyed.