An Inside Look at Medieval Horse Armor

A large group of forgotten combatants stare out at us every day from the annals of war history. They are visible to us in everything from ancient stone reliefs to elegant oil paintings to scratched early black-and-white photos; they regularly appear in statuary alongside famous war leaders, and they have taken part in too many historical battles to name. They are horses, and many avid military history enthusiasts usually don’t give much pause to think about them. This is because horses are animals and, as such, are often taken for granted.

Considered within conflict history, horses have often been viewed as little more than vehicles or baggage conveyors for warriors of the past. Yet horses were warriors in their own right.

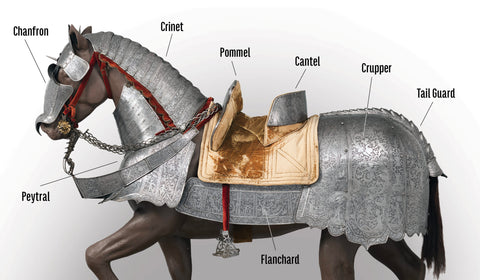

In addition to bearing the stresses of combat, horses have also borne another burden alongside soldiers of yore—armor.

In medieval and Renaissance Europe, horses were essential for battle as well as tournament sports like jousting. A complete set of horse armor could weigh between 40 to 90 pounds—and that’s not even counting the added weight of the rider.

Most horses selected for battle or tournament challenges were robust breeds—the four-legged equivalent of tanks. Breeds capable of charging into combat wearing armor were known as destriers, coursers and rounceys. As with humans, armor for a horse was not always intended for merely protective functions, but could also be ceremonial and an indicator of its owner’s status in society.

While body armor for horses varied according to the riders’ culture, traditions and available materials, a universal and common element of horse armor across the globe tended to be the chanfron (also called shaffron or chamfron), head and facial armor which might fairly be called a “horse helmet.” The following is a roundup of some unusual examples of chanfrons and other elements of horse armor from around the world.

This ornate

Italian chanfron dating from 1575 sports a golden spike resembling the horn of

a unicorn, a powerful beast in medieval lore.

This colorful chanfron was made for Polish-

Lithuanian noble Mikolaj “the Black” Radziwill and features eye protectors.

This late 15th

century German chanfron was made from a single piece of forged and polished

metal and has a hole in the horse’s forehead area where its owner’s coat of

arms might once have been attached. Due to horses’ sensitivity, protection for

a horse’s head would not only deflect injuries but help a rider stay in

control.

This imposing

example of a half-chanfron made circa 1553 draws attention to the

modifications that could be made to horse armor–in this case, ear guards,

which could also be detached. There are also protruding flanges over the

horse’s eyes. A Latin inscription on the central plate reads: “The word of the

Lord endures forever.”

This late 15th century chanfron, thought

to be of Italian craftsmanship, was made for the French royal court. It is

designed as a dragon’s head. Redecorated in 1539 with gold-damascened motifs,

including dolphins, the fleur-de-lis, and the letter “H,” it was presumably

worn by the mount of France’s King Henry II before his ascent to the throne.

It is an example of ceremonial armor intended to create a heroic spectacle and

emphasize the prominence of a horse’s rider in society.

This half-

chanfron belonged to the captain of the guards of Austria’s Holy Roman Emperor

Ferdinand I. It was likely worn during royal tournament games in Vienna in

1560. It was but one piece of a collection of over 60 horse armor pieces.

This late

15th century Italian-made crinet, or neck armor, was modified in the 19th

century to include mail fringe and guards for the horse’s eyes and ears.

This fragment of an

ornate gilt Italian crinet from the late 16th century is thought to have been

part of an original with 10 or more plates. It is adorned with birds, angels

and grotesque creatures.

This peytral (horse breastplate) is of Tibetan or

Mongolian origin. Like European horse armor, it is decorated with symbols of

spiritual significance. A “wish-granting jewel” on a lotus throne appears at

the center of the upper piece.

This Spanish chanfron is of the type

fielded by the horses of conquistadors.

A Dutch chanfron features images of battle

trophies and bound captives, and a unicorn spike framed in fleur-de-lis. It

once had full leather lining.

This striking chanfron, thought to be of Tibetan

origin, was possibly designed for a general or king. Damascened with gold and

silver, it emphasizes the horse’s eyes and even provides artificial golden

eyebrows.

A unicorn-

style spike appears on this chanfron. Unicorns were regarded as especially

wild and fierce beasts, and thus could have emphasized power.

This “blind”

chanfron would have been used to prevent a horse from shying away from

jousting and possibly also to provide extra eye protection from a jousting

lance.

The peytral protected

a horse’s chest and shoulders in battle and in tournaments. This example made

of shaped and hardened leather is of Spanish origin.

The

crupper, or rump armor, provided defense for a horse’s croup, hips and

hindquarters; it also protected the sensitive upper tail area.

This Italian crupper dating from the late 16th

century and made for a nobleman features an elaborate tail guard and symbolic

imagery, including David and Goliath and mythical hero Marcus Curtius, who

allegedly offered himself to the gods of Hades to save Rome. Curtius was

likely a metaphor for military sacrifice.

A German chanfron features plates attached

with hinges to form cheekpieces and protection for the back of the skull.

This peytral

forms part of a set with the crupper opposite. It depicts the Biblical story

of Judith slaying enemy commander Holofernes among other legends.

This rare

chanfron is from India and dates back to the 17th century. It is flexible due

to its textile backing and features cheekpieces.

This gilt chanfron, of French origin, showcases

a good example of ear guards that allowed a horse’s ears total freedom of

movement.