Abraham Lincoln’s Embrace of Foreign-Born Fighters

In the earliest days of Union enlistment in New York City, anyone willing to volunteer was welcome at recruitment offices—including the foreign-born. Language barriers proved no obstacle, particularly among Germans. After all, German support had helped Abraham Lincoln win the presidency in 1860.

After the fall of Fort Sumter and the call for 75,000 militia to suppress the rebellion, Lincoln wisely concluded that a war to save the Union must not be an exclusively native-born undertaking. So he launched a concerted effort to lure marquee commanders from various ethnic backgrounds, regardless of their politics (though he did resist abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ early pleas for the enlistment of free Blacks).

One of Lincoln’s first such acts was to order his secretary of war to appoint “Col. Julian Allen, a Polish gentleman, naturalized,” who proposed “raising a Regiment of our citizens of his nationality, to serve in our Army.” After some initial resistance from the War Department, Allen got his commission.

Army regulations at the time explicitly stated: “No volunteer will be mustered into the service who is unable to speak the English language.” That rule would simply be ignored. From the outset, the restriction hardly stemmed the early enthusiasm of the foreign-born to don the U.S. Army uniform, even if the uniforms themselves reflected more the ethnic background of the recruits than the cohesion of the supposedly united states.

Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz had a mixed military

career, but had a successful postwar Republican Party political career.

That spring, German-born New York Herald correspondent Henry Villard seemed “surprised”—but clearly proud—to observe freshly minted “infantry dressed in the genuine Bavarian uniform….Prussian uniforms, too; the ‘Garibaldi Guards’ in the legendary red blouses and bersaglieri [Italian infantry] hats,” as well as “‘Zouaves’ and ‘Turcoes’ [North African infantrymen], clothed as in the French army, with some fanciful American features grafted upon them.”

Before long, Lincoln granted a request by Carl Schurz, the recently named U.S. minister to Spain, to abandon his post in Madrid and raise a regiment in New York. Although his initial recruitment efforts fell short, Schurz won a military commission anyway, and served in the Army of the Potomac. In 1863, however, he earned damning criticism when his men fled from a Confederate assault at Chancellorsville. Most officers subject to such castigation would have faced demotion or dismissal. But Schurz still exerted enormous influence—over the German-born community as well as Lincoln—for his tireless work in the 1860 campaign. A gifted orator, he managed to convince Lincoln to continue backing him even as he leveled injudicious criticism (privately, at least) on his commander-in-chief.

Franz Sigel did not lack bravery; he

was wounded at Second Bull Run, but also did not have a lot of luck when it

came to winning battles.

Then there was the case of Franz Sigel, a 36-year-old German-born general who notched an even more dubious record in the West. From the outset of the war, however, Sigel proved a magnet for German recruitment. “I Fights Mit Sigel” became a rallying cry among German-speaking soldiers. Each time Lincoln sought to downgrade Sigel, the outcry from Germans proved overpowering. In 1864, when Lincoln briefly faced a third-party reelection challenge, many of those expressing support for the insurgency cited the president’s alleged injustices against Sigel.

Irish Leaders, Mixed Results

If German Americans contributed the largest foreign-born contingent in the Federal army, Irish Americans proved a close second. Some 150,000 Irishmen took up arms for the Union.

Such a patriotic response from this overwhelmingly pro-Democratic community could not have been predicted before the shelling of Fort Sumter. Only a week later, at a massive rally at New York’s Union Square, Irish lawyer Richard O’Gormon addressed the crowd of 100,000: “[W]hen I assumed the rights of a citizen, I assumed, too, the duties of a citizen.” Lincoln, he admitted, “is not the President of my choice. No matter. He is the President chosen under the Constitution.” The attack on Sumter was worse “than if the combined fleets of England had threatened to devastate our coast.”

Not yet completely reassured about Irish loyalty, Lincoln had summoned another prominent New York attorney, James T. Brady, and beseeched him to raise and lead the first Irish brigade. Brady protested that he possessed no experience in such matters. “You know plenty of Irish who do,” Lincoln countered, “…and as to the appointment of officers, did you ever know an Irishman who would decline an office or refuse a pair of epaulets, or do anything but fight gallantly after he had them?”

Like O’Gormon, Brady was a longtime Democrat, but at Lincoln’s urging, he began successfully recruiting, though he never took up arms himself. The Irish-American newspaper now called on its readers “to be true to the land of your adoption in this crisis of her fate.”

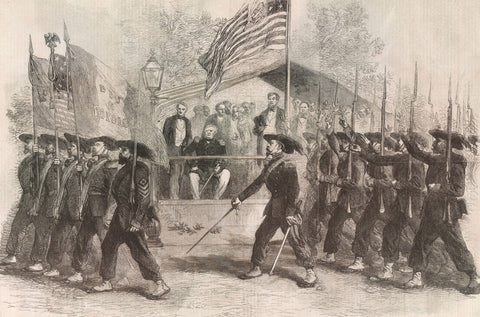

The overwhelmingly Irish 69th Regiment of the New York State Militia marched to the defense of Washington on April 23, 1861, accompanied by the “stormy cheers” of some half a million onlookers. Lincoln had called for volunteers on April 15, and it had taken only days to muster the 69th. “So great was the anxiety to join the ranks” that three times more men volunteered than could be accommodated in the regiment.

Father William Corby gives absolution to the 69th New

York as it and the other regiments of the Irish Brigade, the 63rd and 88th New

York and the “honorary Irish” 29th Massachusetts, attack the notorious Sunken

Road at Antietam on September 17, 1862. The brigade suffered about 40 percent

casualties during the assault.

Leading the regiment downtown that day was 33-year-old Colonel Michael Corcoran. The onetime tavern clerk from County Sligo had led the unit for two years. In 1860, he had aroused both municipal fury and ethnic pride by refusing to assemble his men to welcome the Prince of Wales to New York, arguing that the heir to the British throne represented “the oppressor of Ireland.” Corcoran’s defiance earned him a court-martial that was still pending, only to be shelved once the rebellion began; he was too well-suited to his new role. An active member of the Fenian Brotherhood, which supported Irish independence, Corcoran was also a politically active local Democrat. Above all, New York Archbishop John Hughes believed “Corcoran should be appointed” to lead the Irish defense of the Union, and Lincoln replied that “my own judgment concurs.”

In an uncirculated, likely misdated, and largely forgotten memorandum he composed sometime that spring, the president identified Corcoran and two other noted Irishmen—James Shields and Thomas Francis Meagher—as ideal Union commanders. Lincoln managed to recruit all three, albeit with mixed results.

Shields, Lincoln’s onetime Illinois political rival and a former U.S. senator, had been for several years a resident of California. When Fort Sumter fell, he was even farther from home: in Mazatlán, Mexico, on a business venture and extended honeymoon with his Irish-born bride. Shields’ experience in the Mexican War, plus his nativity and status, made him an ideal general, so Lincoln nominated him for a command.

The gesture was magnanimous on several levels. Not only was Shields a Democrat; he had also opposed Lincoln for a U.S. Senate seat from Illinois in 1855 (both men lost). Most noteworthy of all, Shields had once challenged young Lincoln to a duel over a series of incendiary newspaper satires lambasting him in language most modern readers would call anti-Irish. The slander was probably more the work of Lincoln’s fiancée, Mary Todd, than of her future husband, but Lincoln gallantly assumed responsibility and the two men headed to a dueling ground to settle scores.

Only when Lincoln chose weapons for the contest—broadswords that would have given the long-armed lawyer a distinct advantage over his smaller challenger—did the two call off their fight. Now, 20 years later, the politician whom Lincoln had once publicly mocked quickly “tendered his services to his old friend, now President of the United States”—something of an exaggeration. For a time, in fact, Shields remained frustratingly out of reach. Claiming he was still hindered by wounds he had suffered in Mexico—which apparently did not limit his prolonged attentions to his young new wife—he delayed his return for weeks. This gave foes who questioned his loyalty ample time to try blocking his appointment. When Shields finally started for home in late November, San Jose newspaperman F.B. Murdock warned Lincoln that “if civil war should break out on the Pacific coast, Gen. Shields would be found on the Rebel side.” Yet the president remained committed to recruiting both Democrats and the foreign-born to fight the enemy—even a former enemy of his own.

Shields finally reached Washington in January 1862, and on the 8th met with Lincoln at the White House. There, Shields apparently convinced him of his “self-sacrificing cooperation with the government.” The doubtlessly tense reunion ended with the president expressing “hearty and unreserved confidence” in Shields, whose appointment went through as planned. As Lincoln hoped, his commission generated nearly as much enthusiasm in the Irish and Democratic press as Sigel had inspired in the German. In New York, a special committee began recruiting men to serve under Shields as “a distinctive representation of Irish valor and patriotism.”

Both Michael Corcoran, left, and James Shields,

right, drew their first breaths in Ireland. Corcoran raised five Union

regiments. Shields has a political distinction that will likely never be

surpassed. He served as a senator from three different states, Illinois,

Minnesota, and Missouri.

Shields’ war, however, did not go as his admirers hoped. Assigned to the Department of the Shenandoah, he suffered a serious wound at the First Battle of Kernstown in March and had to be carried from the field. In his absence, Union forces achieved a modest victory over “Stonewall” Jackson that prompted Shields’ friend to claim he was cheated out of credit for the success. Then in a June rematch at Port Republic, Jackson easily outmaneuvered Shields. Now an aide claimed that were it not for “the blunder of a subordinate,” Shields might have been remembered as “one of the Shermans, Sheridans, and Meades” of the war.” He thereafter earned few command opportunities. In the summer, Lincoln offered some solace by promoting him to the rank of major general, but in an extraordinary rebuff to a onetime member, the Senate refused to confirm him.

Shields’ army career never rebounded. With no options remaining, the president transferred him to the military Department of the Pacific in San Francisco. Shields thus enjoyed a government-funded transcontinental trip home and then, no doubt by pre-arrangement, resigned from the service. Before him lay yet another stint in the U. S. Senate.

The third Irish military leader mentioned in Lincoln’s 1861 “Irish” memo was Thomas Meagher, a celebrated resistance fighter in Ireland who earned a devoted following on both sides of the Atlantic. Once banished to a Tasmanian penal colony by the British, he had made a daring escape, reached America, established an Irish newspaper in Boston, and arrived in New York to be greeted as an “apostle of freedom.”

Meagher had expressed initial sympathy for Southern independence, but after Sumter, advised followers that Union loyalty was “not only our duty to America, but also to Ireland.” Meagher then raised a Zouave company—his slogan was “Young Irishmen to Arms!”—and marched south as part of Corcoran’s 69th, his soldiers’ colorful, Middle Eastern-style regalia a vivid contrast to the drab uniforms worn by the regiment’s other Irish-born volunteers.

That July, he fought under Corcoran at First Bull Run. The unit lost 38 killed, 59 wounded, and 95 missing, but endured none of the humiliation heaped on the Union Army by the press over its frenzied retreat. New York blueblood George Templeton Strong, no friend of the Irish, acknowledged that “Corcoran’s Irishmen are said to have fought especially well, and have suffered much.” Indeed, even in withdrawing from the field, the 69th helped safeguard the Army of the Potomac’s rear flank. Despite the chaos, Meagher managed to reorganize his men and lead them back to Washington to fight another day.

Corcoran was not so fortunate. Toward the end of the fray, “standing like a rock in the whirlpool,” he fell into Confederate hands. Taken south as a prisoner of war, he became, in effect, a living martyr. From captivity, he issued a stirring message that sounded at once pro-Union and pro-immigration: “One half of my heart is Erin’s, and the other half is America’s. God bless America, and ever preserve her as the asylum of all the oppressed of the earth.” In Corcoran’s absence, command of the 69th fell to Meagher, who encamped his battered men on Arlington Heights above Washington.

On July 23, Lincoln rode to the regiment’s headquarters, where the exhausted troops summoned “the greatest enthusiasm” to welcome their commander-in-chief. As Lincoln knew, these and other battle-scarred volunteers were now eligible to leave the service, their original three-month enlistment about to end. According to one newspaper account: “The President asked if they intended to re-enlist? The reply was that ‘they would if the President desired it.’ He announced emphatically that he did…complimenting them upon their brave and heroic work….This was received with cheers and the determination expressed to go in for the war and stand by the government and the old flag forever.” Meagher confirmed that his troops greatly enjoyed Lincoln’s “affable manner and cheerful badinage,” which “made him an especial favorite with these rough- and-ready appreciators of genuine kindness and good humor.”

Demobilized a few weeks later, the 69th returned to New York. On July 7, thousands of well-wishers massed at Battery Park on the southern tip of Manhattan to provide the kind of jubilant welcome usually reserved for those who had won battles. Ethnic pride still counted more than martial accomplishment, and sustaining Irish loyalty remained the highest of priorities. As one writer observed: “The entrance of the 69th” produced “a popular ovation…in the hearts of the people.”

“Large, corpulent, and powerful of body; plump and

ruddy–or as some would say, bloated–of face; with resolute mouth and…piercing

blue eyes….This was ‘Meagher of the Sword,’” was how correspondent George

Alfred Townsend recalled Brig. Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher.

Meagher reemerged for a patriotic rally on Manhattan’s then-rural Upper East Side. There he echoed Lincoln’s recent plea for reenlistment: “ I ask no Irishman to do that which I myself am not prepared to do. My heart, my arm, my life is pledged to the National cause, and to the last it will be my highest pride, as I conceive it to be my holiest duty and obligation, to share its fortunes.”

A few days later, Archbishop Hughes conveyed his undiminished confidence in Meagher to the administration. Lincoln responded by offering Meagher a fresh commission as a major general—as long as he agreed to raise another all-Irish regiment. The president still believed such units provided as much symbolic impact as the German companies Sigel had raised in the West—perhaps more, since most Irish enlistees were Democrats whose loyalty reflected the non- partisan nature of the Union war effort.

Lincoln's Legacy on Immigration

Lincoln’s politically wise dependence on foreign-born troops and officers led to mixed results on the battlefield. The reputation of German soldiers fell precipitously after Chancellorsville, and cascaded when Maj. Gen. Alexander Schimmelfennig was widely reported to have sought shelter in a Gettysburg pigsty after the first day of fighting there. Irish troops, meanwhile, won praise for their courage amid carnage not only at Gettysburg, but earlier at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. In the last two years of the war, they became known as the “Fighting Irish,” a sobriquet that, by legend, had been assigned them by none other than Robert E. Lee. Eventually, the staggering casualty rate among Irish soldiers took its toll—not only on the ranks, but also on the morale of home-front Irish Catholics. Two weeks after Gettysburg, New York Irish rioted, looted, burned, and murdered civilians—predominately Blacks—to protest the new military draft. Irishmen once willing to defend the Union now came to believe they were fighting to liberate emancipated Blacks likely to undercut their already low wages.

By December, Lincoln responded not with resentment toward immigrants, but with remarkable forgiveness and foresight. He launched an unprecedented effort to woo more European immigrants to the United States to fill the gaps left in home-front industry, mining, and farms by the deaths of hundreds of thousands of young men in battle.

Until then, Lincoln had notched what must be called a mixed record on the issue of immigration. Back in 1844, he had denounced anti-Catholic riots in Philadelphia. But with the rise of the nativist, anti-immigrant “Know Nothing” movement, he attempted with only limited success to “fuse” its adherents with the new, antislavery Republicans. Though he had once defended the right of foreign-born noncitizens to vote in local elections if their state constitutions so mandated, he also routinely accused Irishmen of voting illegally (largely because they voted Democratic).

Meanwhile he developed political alliances with German Protestants who opposed slavery and who, after a few false starts, rallied around Lincoln for the presidency. Following the 1860 election, he rewarded dozens of German supporters with federal jobs. Although he pledged as president-elect to place “aught in the way” of immigrants to America, his vision of immigration remained limited: it did not include people from Asia, and it came with support for the voluntary colonization of blacks and the forced containment of Native Americans.

Still, few expected that in 1864, Lincoln would reintroduce An Act to Encourage Emigration that, remarkably, proposed federal funding to underwrite the expensive ocean passages of prospective migrants. That idea proved a bridge too far for Congress, which scratched the revolutionary idea from the final bill. Even so, the stripped-down legislation imposed new regulations on passenger ships whose overcrowded holds had long made transatlantic passage dangerous.

The new law also improved disembarkation facilities at New York’s Castle Garden and elsewhere; created the first federal Office (later Bureau) of Immigration; and encouraged private companies to advance immigrants the fare for their voyages to America.

Lincoln’s generous initiative opened wide the door to America, gave the federal government a leadership role in regulating and encouraging immigration for the first time, and led directly to the nation-expanding wave of Eastern- and Southern-European immigration that began around 1890.

As the 16th president and wartime commander-in-chief put it in his annual message of 1864: “I regard our emigrants as one of the principal replenishing streams appointed by Providence to repair the ravages of internal war, and its wastes of national strength and health.” The new birth of freedom would require an influx of new Americans to sustain it.

Lincoln had lived up to that belief while the war raged. More than a quarter million foreign-born troops served in Union ranks—not only German and Irish, but Swedish, English, Scottish, Hungarian, Polish, and Italian soldiers as well. As one pro-war German American, Reinhold Solger, perceptively noted: before the war, a foreigner had never been treated as “a full citizen…his very accent defeats the most generous intentions…[and] blood is stronger than naturalization papers.” The Civil War changed that calculus. As Solger rejoiced, the foreign-born demonstrated “a sacrificial spirit, shared by all ranks,” adding: “They may all bless the war for that knowledge.”

this article first appeared in civil war times magazine

This article is adapted with permission from Harold Holzer’s new book,Brought Forth on this Continent: Abraham Lincoln and American Immigration (Dutton, 2024).