A Union Rebel Inside Robert E. Lee’s Family

“[Robert E. Lee Jr.] is off with Jackson & I hope will catch Pope & his cousin Louis Marshall,” General Robert E. Lee wrote to his daughter Mildred on July 28, 1862, not long after Maj. Gen. John Pope had been given command of the Union Army of Virginia. Marshall was his nephew, the son of Lee’s older sister, Anne. “I could forgive the latter for fighting against us, if he had not joined such a miscreant as Pope.” (Lee would send a similarly worded letter to his wife, Mary, asking that she tell their son to “bring in his cousin” the next time she wrote him.)

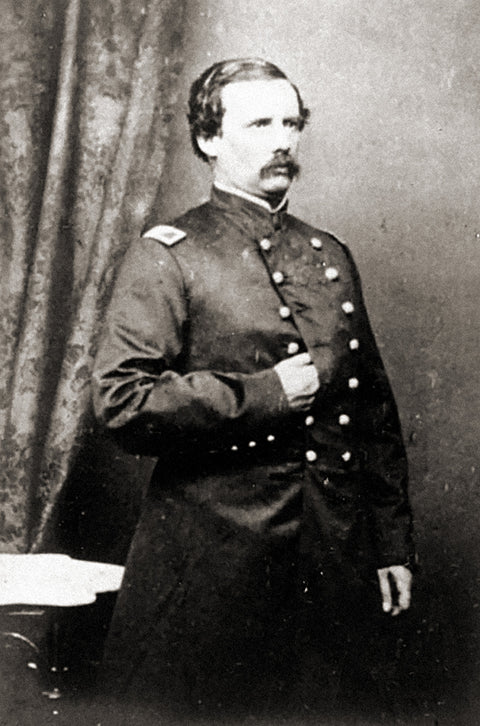

Born in Virginia in 1827, Louis Henry Marshall followed the path of his famed uncle in attending the U.S. Military Academy. Commissioned a second lieutenant with the 3rd U.S. Infantry after graduating in 1849, he served on the frontier, and by 1860 was a captain in the 10th U.S. Infantry. While his uncle, cousins, and other family members in the extended Lee family chose to side with the South, Marshall put his country before kin.

In February 1862, he was appointed an acting aide-de-camp on General Pope’s staff. Brigadier General David S. Stanley recalled that Pope, then commander of the Army of the Mississippi, was “a very witty man and often turned the laugh on his staff officers and others.” He had once poked fun at Marshall’s “demotion” when the soldiers of the Benton Cadets, Missouri Infantry reportedly elected him colonel, then lieutenant colonel, then major after three successive elections. “Why Lou,” Pope remarked in jest, “if those fellows had given you another promotion, they would have landed you in the penitentiary.”

When President Abraham Lincoln appointed Pope to take charge of the Army of Virginia in June 1862, Marshall headed east, pitting him against his uncle and cousins on their home soil.

Marshall was with Pope during that summer’s disastrous Northern Virginia Campaign. In fact, when Captain John Mason Lee, a cousin serving with the Confederate army, encountered Marshall after the Battle of Cedar Mountain, he reported back that he looked to be in a wretched state. Pope had Marshall verbally deliver orders to Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks inquiring whether Banks planned to hold or attack during the eventual Confederate victory. When General Lee heard that Marshall was not in the best of spirits, he wrote Mary: “I am sorry he is in such bad company, but I suppose he could not help it.”

Marshall’s gravesite in Los Angeles.

Marshall escaped Virginia without being captured but was banished west with Pope after Second Bull Run and spent the rest of the war in the Department of the Northwest. He remained in the U.S. Army postwar, serving in Washington, Idaho, and Oregon—notably at the Battle of Three Forks against the Snake Indians—before resigning in 1868, a major in the 23rd U.S. Infantry.

Marshall followed his father to California and lived a humble life as a rancher until his death in Monrovia on October 8, 1891, at age 63. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Los Angeles.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of America's Civil War magazine.